Cardinal Charles Bo visited the United Kingdom during the last part of May and this post contains some of his remarks and subsequent comments:

Reflection on the visit by Ben Rogers:

https://forbinfull.org/2016/07/01/on-the-road-with-cardinal-bo-a-personal-reflection/

June 2016: call for peace…

http://myanmar.rveritas-asia.org/news-content?news_id_token=159xeb190043d70879a02761c3858d4dfaa3

“We should never be discouraged. Never give up! Life is rowing against the current. Do not give up when the changes in the country are too slow. Listen again to the words of Isaiah as you remember your own times of hopelessness. ‘You shall no more be termed forsaken, and your land shall no more be termed desolate…You shall be called by a new name…You shall be a crown of beauty in the hand of the Lord.’ – Cardinal Bo

You might appreciate Cardinal Bo’s recent homily for the Celebration of the Jubilee Year of Mercy:http://myanmar.rveritas-asia.org/news-content?news_id_token=153x51a0fa9d483f8061fd7b8042a20256e6

See:

http://www.catholicnews.org.uk/Home/Podcasts/Catholic-News/Burma-s-first-Cardinal

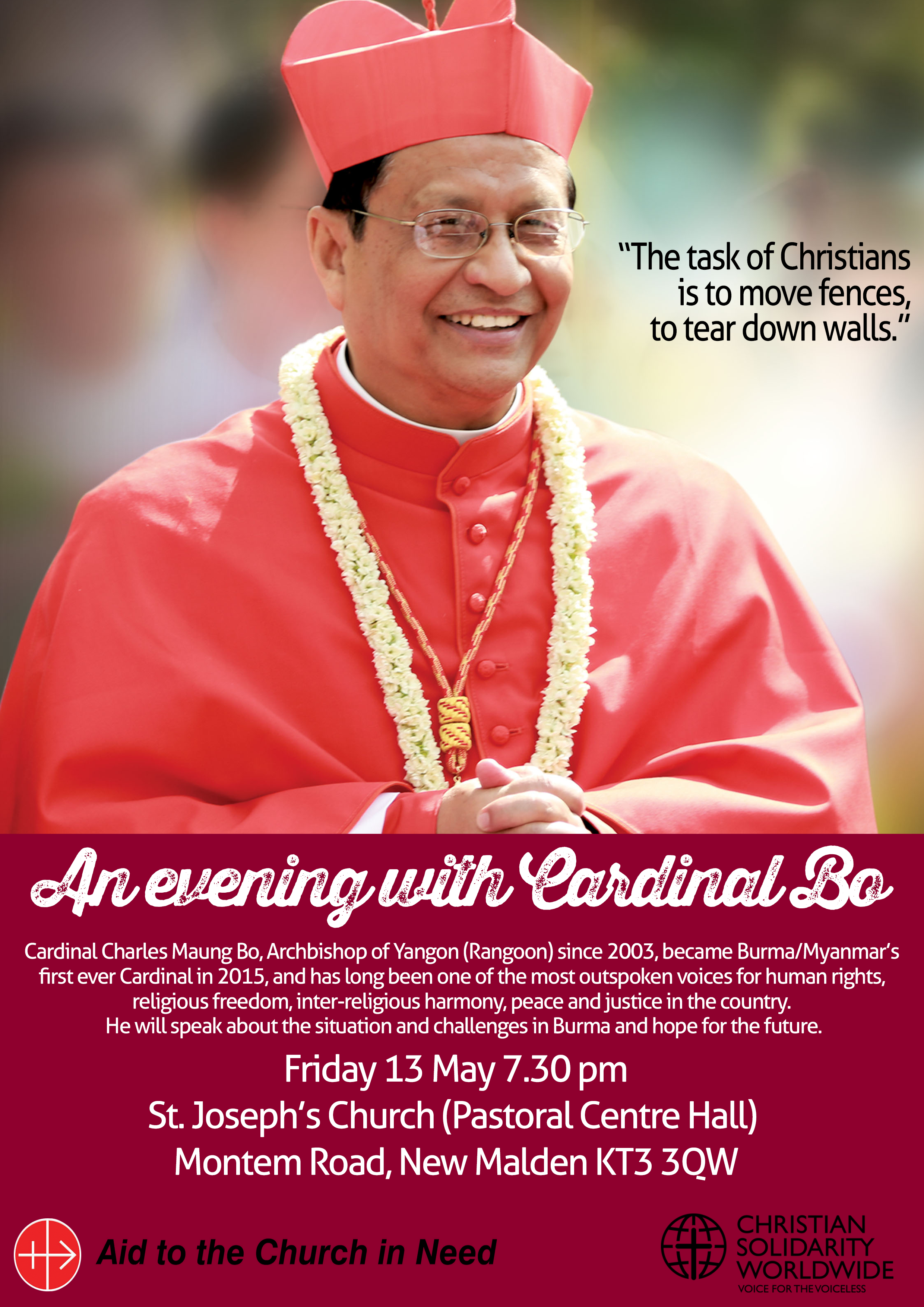

His Eminence Cardinal Charles Maung Bo, Archbishop of Yangon (Rangoon) since 2003, became Burma/Myanmar’s first ever Cardinal in 2015, and has long been one of the most outspoken voices for human rights, religious freedom, inter-religious harmony, peace and justice in the country. Upon his appointment as Cardinal, he told the media, “I want to be a voice for the voiceless”. A profile in La Stampa headlined ‘The cardinal who brings poetry to the faith’ described him as one who “speaks like a poet but his evangelical message covers the economy, society and politics”.

Cardinal Bo has played a key role in his country’s struggle for freedom. In his Easter message in 2014, he said “The task of Christians is to move fences, to tear down walls.” His country, he said, has been through “our way of the Cross for the last five decades”. A nation “was crucified and left to hang on the cross of humanity. We were a Good Friday people. Easter was a distant dream”. But today, he adds, “We are an Easter people. There are streaks of hope today.” In his Christmas homily the same year, he said, “Do not be afraid. Do not be afraid to seek your rights to dignity. Do not be afraid to dream, to reimagine a new [Burma/Myanmar] where justice and righteousness flow like a river.”

Ordained a priest of the Salesians of Don Bosco in 1976, he became Bishop of Lashio in 1990 and subsequently served as Bishop of Pathein and as Apostolic Administrator of Mandalay Archbiocese. In December 2015 he celebrated his 25th Episcopal Jubilee. His motto is ‘Omnia Possum in Eo’ (Philippians 4:13).

Cardinal Bo is Chairman of the Office of Human Development in the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences, a member of the Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue, and since 2015 a member of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, and the Pontifical Council for Culture. In January 2016 he served as the Papal Legate at the International Eucharistic Congress.

His Eminence has been visiting the United Kingdom as a guest of Christian Solidarity Worldwide, Missio, Aid to the Church in Need and the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, and in Scotland as a guest of these organisations and the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Scotland.

Cardinal Bo has repeatedly spoken out against rising religious intolerance in Burma/Myanmar, and for inter-religious harmony, dialogue and peace. In his message on Parents’ Day on 26 July 2015, he criticised the government for failing in its parental duty to the nation to prevent religious hatred and called for the establishment of a ‘family spirit’ for the country:

Today we in Myanmar remember that in our culture, in Buddhist culture parents are venerated like Gods. And our rulers in Myanmar traditionally were treated like parents. Our traditions enjoined on them the right and duty to promote the wellbeing of all. For fifty years in the dark days, we had no family. When democracy came, we hoped it would bring the family spirit of all. Great expectations were laid on our President and also on the leader of the opposition: Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. A nation looks up to them to make this nation a true family. They were to be our parents. But after four years, Myanmar is still to be a family.

For centuries we have lived together as brothers and sisters. Various faiths lived in harmony. For five decades Myanmar was on the radar of a compassionate world, because its people were oppressed by evil men. But from 2010, even after the country opened up, Myanmar has once again been on the radar. There are people who do not want the family spirit to grow…Our brothers and sisters, from all religions and races are affected by this hatred…True love is restricted among religions through [the new] marriage act.

We pray for justice and fair play that this nation may rise up to its glorious days through unity. Let the parents of this nation make this a nation of freedom, a nation that is not seeking glory of the past, but let our parents of this nation dream of a great country [which is a] family of rainbow people. Let us affirm the dignity of diversity but build the family spirit.8

In his Easter message in 2015, Cardinal Bo addressed the country’s decades of ethnic conflict:

The country needs reconciliation among communities. A war rages in the northern Kachin and Shan regions. In Rakhine region there is conflict between communities…The blood of the innocents cries out for reconciliation. How long can the ethnic communities cry for justice and reconciliation? Blessed are the peacemakers. May peace be to this house (Luke 10:5). Ethnic communities are crucified in this country. They are the Good Friday people…[The] Myanmar Church works for reconciliation based on human dignity.9

A similar theme featured in his Easter message in 2014:

Reconciliation among communities in Myanmar: St Paul reminds us that we are all part of the mystical body of Christ, each one forming the different parts of the body. (1 Corinthians 12:12-30). ‘We are brothers and sisters’ of this great nation. Without this attitude there can be no peace in the world, says Pope Francis. The binary configuration of this nation’s history with the Bamar majority claiming all rights and challenging others to the status of nothing has wrought wars, conflict and unbearable suffering for all. The risen Christ brought a single message: ‘Peace be with you,’ (Luke 24:36). Pope John Paul contextualised Christ’s perennial message, saying “If you want peace, work for justice.” Justice is in short supply in ethnic areas. For the common good all stakeholders need to address justice issues. The God of the Old Testament and the God of the Resurrection bases his domain on justice. Return to justice and return to reconciliation in this nation of 135 communities. Diversity is dignity. Respect and reconcile.

In an article in the Myanmar Times in August 2013, the Cardinal renewed his call for respect for diversity:

True peace and real freedom, however, hinge on an issue that has yet to be addressed: respect for Myanmar’s ethnic and religious diversity. Unless and until a genuine peace process is established with the ethnic nationalities, involving a nationwide political dialogue about the constitutional arrangements for the country, ceasefires will remain fragile and will not result in an end to war…A distinct but inter-related and equally urgent challenge that must be addressed is religious harmony. The past year has seen shocking violence against Muslims in Myanmar, starting in Rakhine State in June 2012 but spreading to Meiktila, Oakkan, Lashio and other towns and cities. The violence and anti-Muslim propaganda has highlighted a deep-seated issue in

Myanmar society: how to live with our deepest differences. No society can be truly democratic, free and peaceful if it does not respect – and even celebrate – political, racial and religious diversity, as well as protect the basic human rights of every single person, regardless of race, religion or gender.10

And again in his Christmas message in December 2015, just a few weeks after the elections in which Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy won a landslide, he said:

With the general election of 8th November, our nation sees the dawn of change. It is up to us to allow it to be a bright daylight. Naturally, it is impossible to get a unanimous choice in the election. Although the majority wins in the election the minority cannot be excluded in the nation building. We must overcome the competitions and differences. This year is a year of blessing to each one of you, my brothers and sisters. This is a great time to be in this country. By reconciling with one another, forgetting all the past darkness of hatred, we can make Christ’s message of peace possible to all people of goodwill. So we call upon all men and women of goodwill, bring the great message of peace and prosperity to this nation.

The temptation is to rush into irrational expectations, protests and even rioting. There is a time for everything. It is wise to listen to President John F Kennedy, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.’ Nation building is the task of all of us. Now that the ballot box has spoken and we have leaders who have proved to be morally upright, it is our duty to build a nation without war and want. With goodwill we can and we will do that.

In general, religion teaches to love and care for one another: [the Buddhist concepts of] karuna [compassion] and metta [loving kindness] are the foundations of religions. As we live a virtuous life we are to show love and respect to others. However, the sad reality is that there are incidents of conflict and war in the name of religion. Myanmar’s future depends on the positive role of the religious leaders. All attempts to abuse religion for political purposes need to be resisted by all religions and religious leaders. The goodwill of religion is the capacity to live in harmony with different faiths and religion.

Myanmar is a nation which is comprised of different tribes. This image of our nation must be safeguarded by all means. Myanmar has to solve its identity crisis, which has dragged the country into chronic wars and displacement. After sixty years of ‘independence’ we are a bleeding nation. Peace has its dividends for all. We call upon all tribes and nationalities to engage in peaceful negotiations for durable peace. In goodwill we all shall explore the federal solution to our problems. However, peace cannot be built just on paper. Peace can be achieved only with our goodwill and sincere hearts.

In many of his messages on the theme of inter-religious harmony, Cardinal Bo points to the principles of the country’s majority religion, Buddhism, and particularly the concepts of metta (loving kindness} and karuna (compassion):

Counting on God’s mercy, all of us need to seek mercy and forgiveness through the sacrament of confession. It is the sacrament of mercy. We need to cleanse ourselves from the sin of judging others. We need to develop an attitude of understanding. As we are aware our Buddhist brothers and sisters in Myanmar have two eyes of spiritual attainment: mercy and compassion (metta and karuna). Metta Bhavana is a way of developing loving kindness towards all. We need this grace. St Paul affirms this: Not by our works but by his mercy we are saved (Titus 3:5). In this jubilee year, our attitude needs to be one of loving kindness, forgiveness to those who live with us. By renewing ourselves spiritually we are ready to reflect the God of mercy in our lives. ‘Blessed are the merciful for they shall obtain mercy’ (Matthew 5:7)

Cardinal Bo has been particularly bold in speaking out against the militant Buddhist nationalist movement that preaches hatred of non-Buddhists, particularly Muslims, referring to them repeatedly as ‘merchants of death’ and ‘hatemongers’:

First of all we need to understand that the acts of evil perpetrated in the name of religion and race are committed by a handful of merchants of death. Buddhism is a great and majestic religion that teaches compassion. Those who teach hatred in the name of that religion of the prophet of compassion are the first enemies of Buddhism. We shall not allow a handful to tarnish the great religion that remains the light of Asia. These anti-Buddhists do not have a place in a new Myanmar.

Democracy

Cardinal Bo has long been an outspoken voice for democracy in Myanmar. Ahead of the elections in November 2015, he emphasised that federalism is needed if decades of civil war between the military and the ethnic nationalities are to end:

A true federal system that would enhance community based natural resource management is the only way ahead. A true federal state is the only guarantee for peace and environmental justice. A democracy that is truly devolved and decentralised will bring a prosperous and peaceful Myanmar.13

In his Christmas message in 2015, Cardinal Bo welcomed the election of a new government in the country:

We congratulate the NLD who won the election. At the same time we also wish and pray that you may build the nation in spite of enormous challenges that lie in wait. The people of Myanmar have invested their hopes and future in your fragile hands, knowing that the power of empty hands has ‘sent away the mighty and raised the lowly’. You have shown your sagacity by proposing a government of national reconciliation. The Church joins in your goodwill and efforts to bring peace with justice.

And in his Easter message in 2016, he paid tribute to the democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and talked of a ‘new dawn’ for his country:

Today we see another resurrection: resurrection of hope in a frail woman, Aung San Suu Kyi. She was also raised on the tree of suffering for more than 15 years in the jail. Darkness was penetrating Myanmar for more than 50 years. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s suffering and her fortitude amidst the suffering has brought the resurrection of freedom. Today Myanmar can wake up into a dawn of hope because people like Aung San Suu Kyi are willing to be wounded but use that suffering as a redemptive suffering. A new nation is born today, and nurtures the

resurrection of hope of freedom, peace, prosperity and human development.

Human rights

Cardinal Bo has always been a courageous voice for human rights, and he used his first major homily in Myanmar since becoming Cardinal to reiterate that message. At the Celebration of Our Lady of Lourdes at the Nyaung Lay Bin National Marian Centre on 28 February 2015, two weeks after receiving the red biretta, His Eminence said:

We cannot forget millions of our youth living as unsafe migrants in the nearby countries, we cannot forget the farmers who are losing their lands to companies, we cannot forget the thousands who live in the internally displaced communities. In this season of Lent we are called to feel for one another. Just like our Mother Mary stood at the cross she stands today at the gates of the IDP camps, in fellowship with the tears of those innocent girls human trafficked to nearby countries. We should not forget the millions of children who do not go to school. We should not forget the thousands of farmers who have lost their lands in the last two years to big companies.14

In his New Year message in December 2013 and a message on human trafficking in 2014, he gave the people and the Church in Myanmar a challenge, particularly highlighting human trafficking and religious intolerance:

Human trafficking is a virtual hell for millions of vulnerable people. More than a million people are trafficked every year and around 400,000 women are forced into sex slavery. The world is yet to be ashamed of the perpetuation of slavery in the modern forms: South East Asia is the most vulnerable part of the world for the poor. Countries emerging from decades of war and poverty have to sacrifice their sons and daughters on the altar of monetary greed. This region is gasping for dignity with drug lords and traffickers cynically manipulating governments and systems to their gain – in Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia. Myanmar has a depressing history of allowing her sons and daughters to be exploited by every nation on the globe. We are a nation of exodus. An exodus designed and executed by man-made disasters – of six decades of the heartless dictatorship that ensured underdevelopment. In the last two decades more than three million people have been forced into unsafe migration. Our youth fled from poverty, war, from persecution, from lack of education, from lack of any employment. Internally and externally three million of our people are away from their homes. Thousands of our girls languish in unknown corners of neighbouring countries.15

Whatever our religion, we need to refocus our minds on our common humanity and our fraternity as peoples of Myanmar…We need to rediscover the value of ‘unity in diversity’. Myanmar is a multi-ethnic and multi-religious society, rich in ethnic and religious diversity. This diversity is something to celebrate. After the storms, when the sun comes out, we should be able to see that we are a nation of many colours. A rainbow nation. We must build a nation in which every person born on Myanmar’s soil feels at home, has a stake in the country’s future, is treated with equal respect and equal rights, and is accepted and cared for by their neighbours. A nation where the histories, languages, customs and religions of all are respected and celebrated. There must be no second-class people. As Pope Francis says, “In many parts of the world, there seems to be no end to grave offences against fundamental human rights, especially the right to life and the right to religious freedom.” This is true in our corner of the world. Even as talks continue in Kachin State, we hear reports of attacks on villages, looting of churches, and the rape of women and girls. In other parts of our country, we hear of mosques destroyed. We hear of the tragedy of an entire people, known as Rohingyas, treated as if they were not human, consigned to dire conditions in displacement camps or forced to flee the country in boats, embarking on a precarious escape across the seas…We know that many of the Rohingya people have lived in Myanmar for generations, yet they are not accepted as citizens and are rendered stateless. This misery cannot be allowed to continue. Every person born in Myanmar should be recognised as a citizen of Myanmar.16

And he has criticised those who fail to speak out:

Silence can be criminal. Because when evil takes over and suffocates the voice of the just, one cannot remain silent. Let me remind you of the great words of the civil rights leader: The world will have to weep not for the evil deeds of the bad people, but for the appalling silence of the good people. So with Isaiah, we claim: We shall not keep silence. For the sake of the people of Myanmar, her poor, her ethnic communities, her displaced sons and daughters and those unfortunate victims of human trafficking, we shall not keep silence. Myanmar stands at the crossroads of history. Crossroads as the Jews faced after exile. Like the Jews, we too are returning to a land of hope after 50 years of suffocating darkness.17

He used an article in the Washington Post in 2014 to appeal for religious freedom and an end to ethnic conflict:

Burma [Myanmar] is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious country, with a majority Burman, Buddhist population. If Burma is to be truly free, peaceful and prosperous, the rights of all ethnicities and religious faiths must be protected. A movement that has grown in volume and influence threatens this: extreme Buddhist nationalism. Over the past two years, Muslim communities across Burma have suffered horrific violence, whipped up by hate speech preached by extremist Buddhist nationalists. Thousands of Muslims have been displaced, their homes and shops looted and burned. Hundreds have been killed. The crisis is most acute in Rakhine State, where the Rohingyas, who have lived there for generations, are dehumanised and rendered stateless. A humanitarian catastrophe threatens to unfold, and deeply entrenched prejudices continue unchallenged. In the long term, the question of the Rohingyas’ history, identity and status must be addressed, fairly and humanely. They require emergency assistance to meet their basic needs now. Elsewhere, other religious minorities are vulnerable to discrimination. Kachins, primarily Christians, have been forced into refugee camps.

But there is a need for all of us — religious, civil and political leaders — to speak up to counter hate speech with good speech, as well as for the government to bring to justice those who incite discrimination and violence. After decades of oppression, no one wants to limit our newfound freedom of speech. But with freedom comes responsibility. Freedom should not be misused to inspire hatred. All the religions of Burma have a message of peace. Buddhist concepts of metta and karuna (‘loving kindness’ and ‘compassion’), the Muslim greeting ‘Salam’ (‘Peace’) and Christian values of ‘Love your neighbour’ and ’Love your enemy’ must be deployed in building the new Burma. Religious leaders must preach the goodness of their own religions rather than attack others. Unity in diversity is Burma’s destiny, a unity in which we learn to respect the dignity of difference. The international community must help us in this, and in all our struggles. The world must not allow premature euphoria to cause it to turn a blind eye. Burma’s future hangs in the balance.18

In 2016, Cardinal Bo addressed a public meeting on the theme ‘Injustice Anywhere is Injustice Everywhere’:

Discrimination needs to end. Discrimination in language policies, discrimination in religious rights, discrimination in government employments, discrimination in land laws, discrimination in the armed forces, discrimination in judicial processes, discrimination in economic, cultural and social rights of the ethnic people and other discriminations need to end. Unity in Diversity is the only path ahead. Inclusive approach is the only approach for peace.

Having previously served as priest and bishop in dioceses in the ethnic conflict areas, Cardinal Bo has been particularly outspoken on the suffering of the ethnic nationalities:

At this very moment thousands of our ethnic brothers and sisters are languishing in the IDP camps. Think of Kachins, think of Karens, think of Chins, think of Kayahs, think of Shans – how long do they suffer. A threefold attack on them has left them mortally wounded. Attacks on their identity, culture and resources have left them refugees in their own land. Foreign and local capitalists are looting their natural resources. We will be listening to ethnic activists about how resources fuel wars and destroy communities. As a Church we have a great responsibility. We are a rainbow Church – truly representing every tribe in Myanmar. Fifteen dioceses are ethnic in composition. What is the condition of our Christians? Refugees, IDPs, vulnerable to unsafe migration, human trafficking and drugs. We face existential threats as a people. I see a great urgency in protecting the ethnic brothers and sisters from threats that are already destroying their traditional lands. We shall explore advocacy for indigenous rights, especially for the implementation of customary law, we shall be exploring how the economic, social and cultural rights of our people can be protected, we can be exploring how pastoral care be extended to their youth who are vulnerable to human trafficking and drugs.

Poverty

Poverty in Myanmar is another theme which Cardinal Bo regularly highlights, often as a challenge to those in government and those inciting hatred and violence. In an ‘Appeal to the People and Rulers of Myanmar for Peace and Harmony’ issued in September 2015, he said:

Those who forced the parliament to enact the [protection of race and religion] laws have not allowed our representatives to attend to the most urgent needs of the people of Myanmar. Those who worry about religious conversion and sought a law to prevent that may not have noticed that poverty is the common religion of many of our people. 30 percent of our people are poor and in Rakhine and Chin states the rate is 70 percent. As a nation a real conversion is needed for 30 percent of our people who live in the oppressive religion of poverty. The nation with resources needs a road map to pull out our poor out of poverty.

And in his homily titled ‘Mary’s Assumption: Protector and Promoter of Human Dignity’, he said:

This nation is known for her great spiritual wealth. But six decades of evil rule has brought suffocating darkness over us. There are streaks of hope last five years: release of prisoners, lifting of censorship, greater openness to economy, a sense of hope that is seen in the streets of Myanmar. For this we are grateful to our leaders. But darkness refuses to go. The land bills of 2012 threaten to take the rights of traditional farmers. An economy that helps only those who are rich sees millions of our countrymen and -women more impoverished. We seek change. Change based on justice. Change based on love and life. Change based on human dignity, which our Lady affirmed all through her life. She [Mary, Mother of God] is the protector and promoter of human dignity in this land…As in her day, those who rob from the poor will be consigned to flames of history while those who seek justice to the poor will live forever…Let the elections be a clarion call for justice. Let Jesus’ dream of ‘Good news to the poor, liberation to the captives’ (Luke 4:16-19) become a reality in this nation.

In his Parents’ Day message in 2015, he said:

Millions of our youth are outside, away from their parents. We were made poor, kept poor, and the burden of poverty broke our family to pieces. Integrity of family is being eroded by the country’s poverty. Family spirit is weak. Most of the sons and daughters of Myanmar are poor…in Chin State and Rakhine, where the most displacement takes place, poverty is at 70 percent. These states are the origin of most of the migrants who seek unsafe migration. These unsafe migrations have broken families.20

And in his Christmas homily in 2014 he said:

We were reduced to one of the poorest countries on earth!…Poverty and oppression sent millions to exile. Our sons and daughters become the modern day slaves in the nearby countries. We became the least developed country. We became like a blind beggar begging with the golden plate. So we need freedom from fear…Our date with destiny has arrived. Do not be afraid to claim your rights.

And in his reflection on the Year of Mercy, he highlighted the plight of the poor and the relationship between poverty and conflict:

More than ever the world stands in need of mercy to one another. The world is full of hatred and bloodshed today. In the name of religion, vengeance killing is on the rise. Wars are producing millions of refugees. Europe has thousands of refugees pleading for food and shelter. Despite all the good news about elections, Myanmar too stands in need of mercy and compassion. As I write this pastoral letter, more than 100 poor people have been buried alive in the landslides in the jade mines. After five decades of wars, displacement, poverty and migration, our country needs mercy. Mercy to those who suffered and mercy to those who caused those suffering. Our nation needs healing through mercy. Christians need to heal this nation through mercy.

Environment

Environmental degradation is another concern the Cardinal has highlighted, and has linked to poverty and conflict:

Poverty is spreading in Kachin State. Nearly 60 percent of the natural wealth is in the ethnic areas. Peace is possible only when the benefits of natural resources are shared with justice to all, especially the local people. In this we are guided by Laudato Si’, where the Pope has connected environmental degradation with the poverty of the people. There is a clear mandate for the Catholic Church to protect and promote harmony with nature. I wish this seminar comes with an action plan on environmental awareness and a mechanism for Community-Based Natural Resource Management.22

In August 2015, he gave a homily titled ‘An Inescapable Call to Environmental Morality’, and spoke about the impact of climate change on Myanmar:

Cyclone Nargis in 2008 killed more than 150,000, impacting the lives of 2.3 million people, making 800,000 people homeless…The livelihood of 37 million farmers was sent into a spiral of destruction and debt…Thousands of poor families have been put into a rollercoaster of debt and destruction. Our poor do not even know the words ‘global warming’ but they have been victims of climate change for the last ten years…Some of the rich countries, with a total of six percent of the population of the world, produce forty percent of greenhouse gases. But natural disasters have been attacking poor countries for the last thirty years. Ninety percent of the deaths due to natural disasters come from poor countries.

We stand at the crossroads of history. We have lost so much flora and fauna in the last fifty years. Forests and rivers continue to be destroyed. [The] Mekong River, Irrawaddy River and so many rivers in East Asia are dangerously exploited. What were sporadic attacks on our eco system has now turning into chronic illness for our planet. So our gathering here needs to impress upon all of us the urgency of purpose. Evil is marching with glee, destroying human families, destroying God’s gift of nature. The dance of the devil is arrogant. Our silence will be criminal. Since the problem is moral, it needs a moral response. No one is excused from this duty: As Martin Luther King Jr warned, ‘Some are guilty; all of us are responsible.’

Every day 30,000 poor children [around the world] die of starvation. These children are victims of poverty, war and mismanagement. But increasingly they are victims of environmental degradation by companies and profit-oriented industries…[The] Holy Father’s message is a wakeup call to the Church in East Asia. Let our deliberations come up with practical solutions, starting with how to make our churches deeply sensitive to environmental issues; and we need to join hands with like-minded forces in the struggle towards protection of nature.

He also spoke about the impact of natural disasters in his reflection on Mary’s Assumption:

In our situation now, thousands of villages are marooned. Millions need relief assistance. In the high mountains of Hakha to the tapestry of the delta, there is the sad spectacle of people, women and children wading through unending streams of water. There is a way of the Cross today in the length and breadth of Myanmar. But our prayers go to our Lady [Mary, Mother of God], who was standing at the foot of the Cross when everyone deserted her son. With the same faithfulness, our Mother stands with our suffering brothers and sisters today, calling each one of us to journey with our brothers and sisters in this darkest time of their life.

And in his Easter message in 2015, he spoke out against big business cronies ‘looting’ Myanmar’s natural resources:

The teak, timber and jade and other treasures of the people are open to merciless looting. Do not bury our people once again in poverty. Do not open their resources to the international looters and cronies. Myanmar people seek justice and fair play. Protect the Irrawaddy River, mother of all people, from reckless exploitation for gold. This nation was buried in the tomb of oppression and exploitation for six decades. We call for a new resurrection of peace and prosperity to all people.

Education

Finally, Cardinal Bo has been a strong voice for improving education in Myanmar, and has been a fierce critic of past governments’ neglect of education:

Education is a fundamental right. A deliberate policy of not educating our youngsters exposed them to modern forms of slavery in the nearby countries, to drug menace, to human trafficking. Youth is a wounded generation. True reconciliation is possible. We buried three generations of our people without a good education. I urge all concerned: ‘Do not crucify our youth in the tomb of self-pity,’ but offer them the hope of a bright tomorrow through quality education.23

In March 2016, he said:

Knowledge is power. Burma was one of the highly educated nations in the East Asia. The pristine glory of Myanmar universities was the envy of many nations. But now, 60 percent of our children do not finish primary school. For the last six decades a systematic effort has been made to destroy education, forcing three generations of our youngsters to be handicapped. Millions have ended up in modern forms of slavery. The Church has played a major role in educating many nations. We were at the forefront of quality education in this country, till our schools were taken out at midnight. Sadly it was never dawn afterwards. Darkness at noon…We want to sow dreams into our youth. We want to make Catholics an educated, well informed community. We want to empower the poor with quality education. For those thousands who seek solace in the drugs and unsafe migration, we want to show, Myanmar can be a land of opportunity.

Tablet Interview: May 2016:

A man of the peoples

As a new civilian government takes over in Burma, the country’s first cardinal, whose two-week visit to the United Kingdom begins tomorrow with a Celtic-themed Mass in St Andrew’s cathedral, Glasgow, could make a unique contribution towards ending the country’s longstanding civil wars. By RICHARD COCKETT

There are few people who embody the Catholic tradition in Burma as fully as Charles Maung Bo, who in February last year became the country’s first-ever cardinal.

Sitting in his office in Archbishop’s House behind Yangon’s imposing red-brick St. Mary’s Cathedral, this gregarious, engaging prince of the Church recounts the dynastic roots of his faith. He was born in 1948 in a village in Sagaing Division, just north of what was then the country’s second city, Mandalay. His ancestors were among the first Burmans – the majority ethnic group in the country – to be converted to Catholicism by the Portuguese, the earliest Europeans to arrive in the country 500 years ago. His family were devout Catholics, and he was brought up in a very Catholic environment; two of his brothers also tried to join the priesthood. His father died when he was two years old, so he was bought up by his mother. He remembers her saying prayers every day.

So far, so familiar, perhaps, to many Catholic families. But then Bo’s life-story gets more interesting, and a good deal more relevant to the country’s politics today as a new civilian government takes over for the first time since the early 1960s. It will be a new era for this south-east Asian nation of about 50 million people; it now has a government led, in effect, by Nobel peace laureate and leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD), Aung San Suu Kyi, whose party won a landslide election last November, vanquishing the proxy party of the former military rulers.

For a start, as Cardinal Bo points out, it’s rare for an ethnic Burman to be a Catholic. There are about 800,000 Catholics in the country (the second biggest Christian denomination behind the Baptists, who are estimated to number about 1.5m), but the vast majority of them are from the ethnic minorities, the Chin, Karen, Kachin and others on the mountainous fringes of the country. Indeed, reflecting this demographic fact, Burma’s other 19 Catholic bishops are from ethnic backgrounds.

Historically, the division between the majority Burman and the many ethnic minority groups has been the main faultline in the country, the cause of decades of civil wars since the country’s independence in 1948. So the appointment of a Burman as the first cardinal of a Church that many of the majority Buddhist Burmans regard belongs solely to the ethnic minorities has certainly been an event. Bo remarks that he is now regarded as something of a celebrity.

“Being named a cardinal helps a lot”, he says. “I become more international. And the Buddhist community give me more respect and attention.”

When the news that Pope Francis had appointed him a cardinal became known in January last year, the then-military government even sent him a congratulatory letter.

Bo’s position had already enabled him to take a leading role in the country’s inter-faith dialogue, particularly in trying to reconcile Buddhists with Muslim and Christian minorities. Recent years have seen the bloody persecution, some say genocide, of the Muslim Rohingya people in western Rakhine state, violence that, says the Cardinal, “the military government had been encouraging for their own political purposes.”

There has always been discrimination by the Burman Buddhists against other people, he says, but, as far as Christians go, “no clear, distinct persecution on religious grounds”. However, that’s not to say that the Baptists and Catholics haven’t suffered terribly at the hands of the Burman army.

“Because of the conflicts with the ethnic groups”, he argues, “the army see Christians and rebels as enemies of the state, so Christian villages have been burned down, especially in Kachin state. And this is still going on.”

It is here that Cardinal Bo may have a distinctive role to play, since he is also unusual in being a Burman with close ties to the ethnic minorities. As he says, while “most Burmese look down on the ethnic groups”, his whole career has been spent among Burma’s myriad ethnic peoples. Between his ordination as a Salesian priest in 1976 and his appointment as archbishop of Yangon in 2003, he spent most of his time serving as a priest in the ethnic areas, particularly in northern Shan state, towards the Chinese border, a region heavily populated by Shan, Kachin and other less numerous groups. He was appointed the first bishop of the newly-created diocese of Lashio, covering the Shan state, in 1990. As a consequence, he says, he has “always been very familiar and comfortable with the ethnic groups”.

Indeed, just as Cardinal Bo embodies the Catholic tradition, so he is also an embodiment of the sort of sophisticated, multi-ethnic, multi-faith country that Burma now aspires to be. Unlike most Burmans, he positively revels in the country’s diversity. Take his languages. He speaks four dialects of Jinghpaw, the Kachin language, as well as Burmese, a sprinkling of the Karen dialects, some Shan, and faultless English. And, he adds, almost as an afterthought, he can also prepare sermons or celebrations in Tamil.

So Cardinal Bo could have a significant role to play in the peace process that Aung San Suu Kyi has said will be the priority of the new government – to go beyond ceasefires and find a lasting peace between the Burman majority and the Karen, Shan and others. In this sensitive task, Bo says he will guided particularly by the spirit and example of Pope Francis. His encyclical Laudato Si’, with its focus on the ecological crisis linked to social degradation, the gap between rich and poor, and the urgent need to counter “violence, exploitation and selfishness”, is, Bo says, “very relevant” to Burma.

Cardinal Bo is refreshingly candid and clear-minded about the injustice of the leaders of successive military governments, who plundered the wealth of the ethnic-minority lands to enrich themselves while giving nothing back to the people who lived there. Until the “unjust distribution of economy and wealth” is tackled, he says, there will never be lasting peace in Burma. He points in particular to the obscene amounts of money that the military and their cronies make out of their jade mining in Kachin state. The pressure-group Global Witness estimated off-the-books profit just from jade to be around $31 billion in 2014. Cardinal Bo also laments the wholesale deforestation of the country, all for clandestine profits.

These are uncomfortable truths for many in Burma, and such a clear analysis of Burma’s imbalances and injustices might make for some unsettling moments during any peace talks, or future negotiations over a new federal structure for the country or any new model of how to share the country’s mineral wealth more fairly. Yet Cardinal Bo again takes his cue from Pope Francis’s message of “inclusivity”, which, Bo insists, is “an inspiration for us all”. And this is also the Year of Mercy, as he points out, when Francis is calling all people of good will to choose the way of compassion and forgiveness. Even if the Church “might not approve of some people”, he says, it nonetheless has an obligation of pastoral care for all.

Many in Burma are certainly in need of mercy. And if its peoples are to come together in a new era of peace and reconciliation, as the likeable and astute Cardinal Bo points out, it must listen to this message of inclusiveness.

Richard Cockett was South-East Asia correspondent for The Economist from 2010 to 2014. He is the author of Blood, Dreams and Gold: The Changing Face of Burma (Yale University Press).

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Cardinal Bo wrote the following in The Sunday Times (Scotland edition):

Scotland can help Burma to become truly free

The country has come through military oppression and civil war and now has a chance to develop into a peaceful state, writes Charles Maung Bo

Cardinal Charles Maung Bo

May 8 2016, 1:01am,

The Sunday Times

More than 130,000 people have been displaced in the clashes in Rakhine State, and some 60% of children never finish primary school in Burma

ShareSaveSave

Tomorrow, at a civic reception in Glasgow, I will begin my visit to Scotland by offering my very profound condolences for the death of Asad Shah, the Ahmadi Muslim murdered recently in Glasgow.

Intolerance exists around the world, and is a significant challenge in my country of Myanmar. Sadly, it is emerging as a concern in your country too.

Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, stands on the threshold of hope. After more than half a century of brutal oppression at the hands of a succession of military regimes, and more than 60 years of civil war, we have a chance to develop the values of democracy, protect and promote human rights, and work for peace. Myanmar has its first democratically elected government led by Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. For the first time in decades a non-Burman and a non-Buddhist are our vice-presidents.There is a vibrant civil society and a freer media. But there are many, many challenges to confront; our struggle is not over, rather it is changing.

Despite her enormous mandate, Aung San Suu Kyi is barred by the constitution from becoming president. The military retains control of key ministries and holds a quarter of the seats in parliament. So the new government is constrained and the military remains powerful.

Poverty, education, human trafficking, drugs, freedom of expression, health care, constitutional reform and the economy present enormous challenges. Some 60% of children never finish primary school; maternal mortality is the highest in the region; we have the lowest doctor to patient ratio in the region; and we are the second biggest producer of opium in the world.

If Myanmar is to be truly free, peaceful and prosperous, the rights of all ethnicities and religious faiths must be protected. The rights of religious minorities face increasing threats from groups using violence, killing and destruction to insidious campaigns of discrimination, hate speech and restrictive legislation, all based on an extremist, intolerant form of Buddhist nationalism that completely distorts Buddhism’s key teachings of loving kindness and compassion. These are neo-fascist groups, fringe groups trying to become mainstream merchants of hatred, and they pose a grave threat to our fragile nascent democracy.

Last year the outgoing government in Myanmar introduced four new laws, known as the race and religion protection laws, which pose a serious danger for our country. Two of these laws restrict the right to religious conversion and inter-faith marriage. Such rights are among the most basic human rights and shouldn’t be restricted. Section 295 of Myanmar’s penal code, relating to insulting religion, is being used to silence critics of extremist Buddhist nationalism. Criticising the preachers of hate leaves many open to a charge of insulting Buddhism and a jail sentence.

In Rakhine State, tensions between the predominantly Buddhist Rakhine and the Muslim Rohingya erupted in 2012, leaving more than 130,000 displaced and hundreds dead. These people like to call themselves Rohingya while the government and the nationalist groups contest this term. Their plight is an appalling scar on the conscience of this country. Stripped of their citizenship, rejected by neighbouring countries, they are stateless. I appeal for humanitarian aid and political support to help us to resolve this conflict.

Many have been killed in Myanmar’s ethnic and religious conflicts and hundreds of thousands have been displaced. How can the international community assist Myanmar to address these challenges?

Scotland has wrestled with its own questions in recent years over its political status and its destiny as a country. You have grappled with debates over autonomy, self-determination and religious diversity; you have had your own recent and historical experiences of religious intolerance. I would like to learn from you.

I hope that the international community can encourage the new government in Myanmar to invite the special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief to visit my country and assist in addressing human rights. I urge the new government to take action to prevent hate speech and the incitement of violence, to bring the perpetrators of hatred to justice, and to demonstrate moral leadership.

While I hope the new government will not implement the restrictive laws on race and religion, any support from Scotland to encourage these steps would be greatly appreciated.

There is hope today in Myanmar where a long night of tears and sadness is giving way to a new dawn. But our young democracy is fragile and human rights continue to be abused and violated. No society can be truly democratic, free and peaceful if it does not respect political, racial and religious diversity, as well as protect the basic human rights of everyone, regardless of race, religion or gender.

We are a nation of as many colours and creeds and tweeds as the various clans and kilts that make up your nation. I look to our friends around the world to help my country ensure that every person in Myanmar has their rights protected, without discrimination.

Cardinal Charles Maung Bo is the archbishop of Rangoon

————————————————————————

After celebrating Mass in Westminster Cathedral, Burma’s Cardinal Charles Maung Bo delivered a speech at a reception hosted by Missio.

“Human rights is the new catechism of human dignity,” he said.

“It was the Carpenter’s son who proved to be a great challenge to the Roman imperialism two thousand years ago,” said Cardinal Bo. “Without an army, without a sword, Christ’s words shook evil. The power of empty hands. In every age the power of empty hands changes history.”

Thank you very much for your warm welcome. Thanks to all the faithful gathered here. My special thanks to the Missio family. Friends in Missio have stretched their faith into action in every corner of the earth. Thanks for your commendable service to the new churches.

Missio played a major role in provoking the faith into action. Long ago St James castigated a faith that has no contextual relevance. “if good works do not go with it, faith is dead” ( James 2:17). Missio has been mainstreaming the concept of faith in action for decades. It is indeed a graceful and grateful moment for people like me.

Burma was known for decades for its bleeding agony – of oppression, deprivation and war. My country was a gory example how evil can suffocate good. For sixty years, a nation cried from the cross “ if possible let this cup pass away from me”. A constant metaphor was ‘ a nation crucified”. From 1960s, vulnerable people, including Christians bore the brunt of an inhuman military dictatorship. Overnight schools and health facilities were nationalized, depriving the most marginalized in the society quality education. Catholic properties were confisticated. 235 Missionaries were expelled in a short time.

Evil men thought Christ church was administered euthanasia.

But the persecuted church grew. From three dioceses we are now 16 dioceses, from 300 religious today we are more than 2000 religious. Fromm 200 priests we have around 700 priests today. Myanmar church is a confident church, the only organization where every tribe of the country is found. We are a rainbow church. 7 tribes and 135 sub tribes.

This was possible sincerely because of the faith of our people. But this faith was watered by the magnificent show of fellowship by Christians all over the world through organizations like Missio. It was a combat, a combat that believed that evil had an expiry date and the good had none. Even in the darkest moments of oppression in our country, when millions chose to leave the country to work as modern forms of slaves, Christian churches managed to provide protection, education and health care through our institutions, specially the boarding schools.

We are proud to say that the Christian community has not only survived but has educated itself to serve others through Caritas networks. Today we have 16 Caritas offices in the dioceses, serving all people. Caritas is one of the top service providers to the poor in the country through man made and natural disasters.

This was possible because churches in the west have showed an extra ordinary Eucharistic fellowship.

I had a great honor bestowed by our holy father to be the Legate to the 51st International Eucharistic Congress in Cebu Philippines in the beginning of the year. Millions gathered to hear the message about Eucharist. Preacher after preacher focused how Eucharist is a fellowship that unites the billions of Catholics. Yes. Eucharist is not an empty daily ritual. Eucharist is a call to action. We called for a third world war : war against poverty, a war against hatred.

Our faith is a blessing but also challenge. Every time any priest in poor country raises the bread during the consecration time and says “ take and eat” is painfully aware that there will be thousands who will not have bread to eat that. I quoted the data given by UNICEF which says that everyday 30000 children die every day out of malnutrition and starvation. We break bread in an unjust world that buries 10 million children.

This is terrorism. In a world that makes more guns than hospitals inflicts terrorism on the weak and the vulnerable. A culture of pessimism sets in an uncaring world. Is It?

God has sent a prophet of this millennium : Pope Francis. In the mould of the old testament prophets the voice of our Holy Father rises against the culture of indifference. The secular world that has brought of the worship of Golden calf of avarice has jeopardized our very existence. Pope calls for a binary perception of justice : economic justice and environmental justice.

That to me is the call of the hour, the signs of times. It was the great theologian Karl Barth who said “ a true Christian holds Bible in one hand and newspaper in another hand”. God cries out in the inflicted suffering of the innocent. There are burning bushes in many parts of the world today. The poverty stricken populace in the poor countries, the fire of hatred in the middle east, the first of racism in other parts, the fire of human trafficking in the weak countries. As in the time of Moses, through these fires God identifies himself : “ I am the Lord who hears the cry of the poor” ( Ex : 3: 7-8).

Injustice is the root of human suffering. We have tasted that bitter injustice for six decades. Those who resisted are resting in the unknown graves. Amidst all those engulfing darkness, you brothers and sisters from Missio stood by us. It is a poignant Christian witness how little acts of kinds like the faith of a mustard seeds could move mountains of agony.

We are grateful to the world.

But the journey is long.

Missio has journeyed with us in our search for human dignity. What the future holds for all of us? The world has not reached the promised land. Human rights, humanitarian response and Justice and peace are still in the handicapped list in many parts of the world.

Religion can be an instrument of peace but can become a dangerous cognac for disaster when fundamentalism raises its ugly head. The challenge today is how to nurture our people in a culture of peace, a peace which is borne of justice. “ Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice” said Jesus. If you want peace, work for Justice said Pope Paul VI.

This is our primary task. In our country we have formed an inter religious forum : religions for peace, bringing together all religious people for constructive action in the community. Massive efforts needed to eradicate the stereotypes that negates the human dignity. Organisations like Missio need to identify victims of injustice and collaborate in building communities of justice. As a church in Myanmar we are building our justifce and peace networks. We need resources, trainings and networking

The second task is human development. Christ himself extolled : I came to give life, life in full ( John 10:10). In his path breaking encyclical Caritas in Veritate Pope Benedict XVI extolled : Human development, working for justice are not extra to evangelization but part and parcel of evangelization. This is a great challenge to Burma. We have buried two generations without proper education or empowerment. The junta had underdevelopment as a policy. We seek your support in education and health of our youngsters. 60 percent of our population is below the age of 30. Right to education is one of the advocacy issues taken up by our church in Myanmar.

It is indeed a sad world that denies rights to children, rights to women and girls, denies rights to the weak and the vulnerable. Greed and grief they say are the breeding ground for conflicts. There is much grief today – real and illusory – among the people today. Propagating the rights of the people is a form of evangelization. Vatican II, especially the document Gaudiem Et Spes, the synod of bishops 1971 and the encyclicals of John Paul II, Pope Francis point out to this new form of evangelization. “ God so loved the world, that he sent his son, not to condemn but to redeem (John 3:16). Rights awareness is an important task facing our people. In the recently concluded our national seminar the church has decided to mainstream human rights among the Catholics. Human rights is the new catechism of human dignity.

Missio has been helping to build buildings – churches, schools, religious houses etc. Yes we need them. Especially in a country where our assets were stolen with the gun we need to store assets.

But more than building buildings we need to build our people. Let them build their churches and schools. A massive educational program – formal, informal, non formal and vocational training education is needed. We look forward to this support. Our people are talented, intelligent. They need empowerment not charity. More schools, more institutions of learning. Burma stands in dire need of institutions of empowerment and justice.

Thanksgiving is a sweet task. I have come here to thank you for your great generosity. You carried the Eucharist mandate of sharing. You broke the bread of healing, broke the bread of companionship and comfort in our movement of darkness. Burma church is indebted a huge debt of gratitude to all of you.

We as a nation will stand up to justice, peace, human development and integrity of creation. In this long March we are grateful you have walked with us in our moments of brokenness and self doubt.

Now that we are sailing in the early morning hope of a great democracy under the guidance of the democratic icon : Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, we do hope your friendship, your concern and generosity will continue to nurture the hope of the myanmar people. Long have they had their challenges. Now is their date with destiny.

Walk with us. Together we can work wonders, setting the world on fire with Christ’s message of hope and peace and prosperity .

Thank you .

HIS EMINENCE CARDINAL CHARLES MAUNG BO – SPEECH AT ST JOSEPH’S PARISH CHURCH, NEW MALDEN, FRIDAY 13 MAY (FEAST OF OUR LADY OF FATIMA)

Fr Peter, Ben, Ladies and Gentlemen, distinguished guests –

Having had the joy of baptising and receiving my friend Ben Rogers into the Church in St Mary’s Cathedral, Yangon, Myanmar on Palm Sunday three years ago, it is a great pleasure and privilege now to be able to visit his home parish, to meet you, Fr Peter, and friends here, and to see for the first time the community which helped nurture his journey into the Church and continues to nourish his walk of faith.

As many of you will know, Ben and I have worked together for almost a decade, and it was a conversation he and I had one evening a few years ago that opened up the way to his surprising decision to become a Catholic and to do so, at my invitation, in my country of Myanmar. Ben tells his story in his book, From Burma to Rome, to which I had the privilege of writing the Preface, and if you have not already read it, I commend his book to you very heartily. I call Ben a “rascal”, and he is – he has been deported from my country twice, he has visited the conflict areas in remote parts of Myanmar many times, he wrote a biography of the former dictator, and he is a rascal. But the Church, and the world, need such rascals.

It’s a privilege to be here also when I know that Ben’s sponsor into the Church, who accompanied him to Myanmar and whom I had the joy of meeting, Lord Alton of Liverpool, spoke here in this very same room a year or more ago.

It’s wonderful to be with you on this day, the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima. And in the Gospel for today, from St John, we are reminded of Jesus’ words to Peter: “Do you love me?” And then: “Feed my sheep”.

So much of the flock – the Church – in the world today is in desperate need of feeding, of care, of help as they face different trials and tribulations: persecution, displacement, poverty. And so it is a joy to speak here tonight in support of two organisations – Christian Solidarity Worldwide and Aid to the Church in Need – whose work of feeding Christ’s sheep in different ways is of vital importance to the Church and to the needs of the world.

These two organisations work in a beautifully complementary way. CSW, an ecumenical organisation bringing together Christians of different traditions, is a powerful voice for freedom of religion or belief for all people – people of all faiths and none – and for other, associated human rights. I know that they are listened to in the corridors of power, that their efforts to be a voice for the voiceless are effective, and that in this world today where conflict and terror and hatred and violence and religious persecution are rife, their work is desperately needed. I have seen their work in Myanmar, and in February I had the privilege of travelling with them to the United Nations in Geneva where I had the opportunity to speak about the challenges my country faces, and I could see the quality of their advocacy. They are all rascals, but the world needs such rascals.

Aid to the Church in Need similarly serves a vital role in supporting the Church on the frontlines of faith, helping those persecuted for their faith in practical and spiritual ways, publishing detailed and invaluable reports of the persecution of Christians around the world and serving to remind the Church in different parts of the world of the suffering of our persecuted brothers and sisters.

So I commend the work of these two organisations very warmly and enthusiastically.

My country, Myanmar, now stands on the threshold of hope. We were once a Good Friday people, enduring our crucifixion as a nation on the cross of inhumanity and injustice, with five nails: dictatorship, war, displacement, poverty and oppression. Easter seemed a distant dream. My country was buried in the tomb of oppression and exploitation for six decades.

But today, we can perhaps begin to say that we are an Easter people. A new dawn has arisen. But it brings with it fresh challenges: reconciliation and peace-making, religious intolerance, land grabbing, constitutional limitations, and the fragile nature of a nascent democratic transition. And the old dangers have not gone away: the military remains powerful, corruption is widespread, and ethnic conflict continues in some parts of Myanmar.

I don’t know how much you know about Myanmar – previously known as Burma. For about a century it was a British colony; then, on 4 January 1948, it gained its independence, and for a decade we had democracy, even though it was fragile and conflict-ridden. In 1958 the democratic, civilian government handed over power, allegedly willingly and allegedly temporarily, to the military under General Ne Win, with the hope that they would bring stability to the country. In 1960, fresh elections were held and power returned to a civilian, democratically elected government.

But, in 1962, power-hungry Ne Win launched a coup d’etat and for almost fifty years – half a century – Myanmar was under direct military rule.

Elections in 1990 – the first in decades – were overwhelmingly won by the democracy movement led by Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, which had emerged two years previously through a series of mass demonstrations which had been brutally suppressed. But the military regime refused to accept the results of the 1990 elections, imprisoned most of the victors, and continued its grip on power.

In 2010, so-called elections were held but they were a total sham, a fraud, and the government that was elected was a military-led, military-backed regime made up of former Generals who had simply exchanged their uniforms for suits and ties.

And yet, that military-backed government surprised us all when, finally, it came to the point of opening up, beginning to reform, releasing political prisoners who had been in jail for years for demonstrating for democracy, and in November last year the first credible elections were held. Aung San Suu Kyi, after over 15 years of house arrest, led her party to another overwhelming victory, and this time the military accepted the result. A new government took power in March.

Myanmar has woken to a new dawn, with the first democratically elected government led by our Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy. One of the two Vice-Presidents, nominated by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, is an ethnic Chin (one of the ethnic minorities) and a Christian – the first time in decades a non-Burman and a non-Buddhist has held such a position, and a very significant signal that this new government is for all the people, of all races and ethnicities and religions. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi already made it very clear in an interview on the BBC just after the election last November that “hatred has no place” in Myanmar. So we have a chance – for the first time in my lifetime – of making progress towards reconciliation and freedom as a nation. There is a vibrant civil society and a freer media. We know that while evil has an expiry date, hope has no expiry date.

It is, however, not quite as simple as that sounds. That is not the end of the story.

Despite winning an enormous mandate from the people, Aung San Suu Kyi is barred by the Constitution from becoming President. The military, under the Constitution, retain control of three key ministries – Home Affairs, Border Affairs and Defence – and 25% of the seats in Parliament reserved for them. One of the two Vice-Presidents is a military appointee. So the new government is constrained, the military is still very powerful, and the country continues to face enormous challenges. Our journey has not ended; we are simply entering into a new chapter in our continuing struggle for freedom, democracy, human rights, human dignity and peace.

Nevertheless, we can be thankful that after over half a century of brutal oppression at the hands of a succession of military regimes, and after more than sixty years of civil war, we now have the possibility to begin to build a new Myanmar, to develop the values of democracy, to better protect and promote human rights, to work for peace.

And yet there is a very, very long way to go; there are many, many challenges to confront; and no one should think that the election of the new government means that our struggle is over. It is just the very beginning.

The list of challenges is enormous. Poverty, education, human trafficking, drugs, protecting freedom of expression, constitutional reform, the economy, health care – these are all just some of these challenges. In Myanmar today, 60% of children never finish primary school; maternal mortality is the highest in the region; the country has the lowest doctor to patient ratio in the region. Myanmar is the second biggest producer of opium in the world.

Among the biggest challenges are protecting freedom of religion or belief for all, and resolving ethnic conflict. We desperately need to work to defend rights without discrimination, to establish equal rights for all people in Myanmar, of every ethnicity and religion.

Freedom of religion or belief – as it is set out in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – is perhaps the most basic, most foundational human right of all. As Ben and I said in an article we co-authored in The Myanmar Times in 2013: “True peace and real freedom hinge on an issue that has yet to be addressed: respect for Myanmar’s ethnic and religious diversity. Unless and until a genuine peace process is established with the ethnic nationalities, involving a nationwide political dialogue about the constitutional arrangements for the country, ceasefires will remain fragile and will not result in an end to war.” Furthermore, “freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief, as detailed in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is perhaps the most precious and most basic freedom of all. Without the freedom to choose, practise, share and change your beliefs, there is no freedom.”

This is a message I repeat very, very often – in my homilies, in personal statements, in articles and in speeches. When I gave interviews to the media following my appointment as Myanmar’s first-ever Cardinal, I said that I wanted to use the great privilege I now have to be a “voice for the voiceless”, to speak for the marginalised and the poor, and to work for peace among the peoples of different religions in Myanmar.

As I wrote two years ago in the Washington Post, “Myanmar is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious country, with a majority Burman, Buddhist population. If Myanmar is to be truly free, peaceful and prosperous, the rights of all ethnicities and religious faiths must be protected.”

Over the past four years, the rights of religious minorities have come under increasing threat. Starting with the violence in Rakhine State in 2012, spreading to an anti-Muslim campaign in Meikhtila, Oakkan and Lashio in 2013, and to Mandalay in 2014, and then moving from violence, killing and destruction to a more insidious campaign of discrimination, hate speech and restrictive legislation, this movement – which began as a group called ‘969’ and transformed into an organisation known as ‘Ma Ba Tha’ – is based on an extremist, intolerant form of Buddhist nationalism that completely distorts the key teachings of Buddhism – of ‘Metta’, loving kindness, and ‘Karuna’, compassion – and instead preaches hatred and incites violence. I have described this movement as a neo-fascist group, or merchants of hatred, and they continue to pose a threat to our fragile nascent democracy and to the prospects of peace, prosperity and stability.

Last year, the outgoing government in Myanmar introduced a package of four new laws, known as the ‘Protection of Race and Religion Laws’, which pose a serious danger for our country. Two of these laws restrict the right to religious conversion and inter-faith marriage. Such basic rights – whom to marry and what to believe – are among the most basic human rights, and yet these new laws restrict such basic freedoms. As I said several times, these laws threaten the dream of a united Myanmar.

I am also deeply concerned about the misuse of Section 295 of Myanmar’s Penal Code, the section relating to insulting religion. Although originally introduced in the colonial time with the intention of preventing inter-religious conflict, this law is now used to silence critics of extremist Buddhist nationalism. Htin Lin Oo, himself a Buddhist, spoke out criticising the preachers of hate, saying that their message was incompatible with the teachings of Buddhism, and he was charged with insulting Buddhism and was jailed for two years. He was released last month.

In Rakhine State, tensions between the predominantly Buddhist Rakhine and the Muslim Rohingya erupted in 2012, leaving more than 130,000 displaced and hundreds dead.

The plight of the Rohingyas is an appalling scar on the conscience of my country. They are among the most marginalised, dehumanised and persecuted people in the world. They are treated worse than animals. Stripped of their citizenship, rejected by neighbouring countries, they are rendered stateless. No human being deserves to be treated this way. I therefore appeal for assistance: humanitarian aid, and political assistance to help us resolve this conflict. There is a need to bring Rakhine and Rohingya together, to bring them around a table, to bring voices of moderation and peace together to find a solution. Without this, the prospects for genuine peace and true freedom for my country will be denied, for no one can sleep easy at night knowing how one particular people group are dying simply due to their race and religion.

A related challenge is the conflict in the ethnic states. The majority of the Kachin, Chin, Naga and Karenni peoples, and a significant proportion of the Karen, are Christians – and over the decades of armed conflict, the military has turned religion into a tool of oppression. In Chin State, for example, Christian crosses have been destroyed and Chin Christians have been forced to construct Buddhist pagodas in their place. Last year, two Kachin Christian school teachers were raped and murdered. At least 66 churches in Kachin state have been destroyed since the conflict reignited in 2011.

Many have been killed in Myanmar’s ethnic and religious conflicts; and hundreds of thousands have been displaced.

Last December, I celebrated 25 years as a Bishop – my episcopal Jubilee. We held celebrations in my birthplace, a small rural village called Monhla, in central Myanmar, four hours by rough roads from Mandalay. One particular evening we invited a Buddhist monk, a Muslim leader, a Hindu and a Protestant pastor to join us and together we spoke of our vision for inter-faith harmony. Together we lit a candle for peace. Those sort of gestures, those symbolic acts, send a message to grassroots communities and as long as they are followed-up with grassroots action and community life together, they make a difference.

Another challenge is drugs. In Kachin state and northern Shan State, including my former diocese of Lashio, we face a drugs epidemic. We urgently need the help of the international community, not just – as is the case now – by handing out clean needles to addicts, but by helping establish centres for rehabilitation, and assisting in drug eradication. I understand the motives of international agencies distributing clean needles. They want to minimise the spread of HIV/AIDS and reduce the damage done. But we need a bigger vision. We need to help people off drugs; we need to stop the distribution of drugs; and we need to offer our people alternative livelihoods and some hope in life.

Finally, poverty. Myanmar remains one of the world’s poorest countries. If you come to Yangon and you sit in the traffic jams and you observe the new, expensive, imported cars and you visit five-star hotels filled with foreign business people, international NGOs and a new emerging local wealthy and middle-class, you would have one impression of my country. But go out to the slums in Yangon, only a few minutes from the luxury hotels. Go out to the villages and rural areas. Go out to the camps for internally displaced peoples. Or, even within the cities, visit a hospital or a school. And you will see the real Myanmar. A Myanmar of the poor, a Myanmar without adequate health care, a Myanmar which was once the “Rice Bowl” of Asia which boasted one of the most prestigious universities in South-East Asia wrecked by fifty years of corrupt and brutal military rule. The Generals destroyed our economy, ruined our education system and put no investment into public health. They send their own children to elite schools in Singapore; they go to Singapore for medical treatment; they spend most of their budget buying weapons instead of investing in public services. And so we face a huge challenge: to rebuild our education system and to provide proper health care.

So how, in practical ways, can the international community assist the new government and the people and the Church and other religious and ethnic communities in Myanmar to address these challenges? I conclude with just a few specific recommendations.

Firstly, provide support and assistance to help us rebuild our shattered country, develop our education system, tackle the plagues of drugs and HIV/AIDS, stop human trafficking, and end conflict. But do it in a way that empowers rather than imposes, that respects and strengthens the people of Myanmar rather than recolonises us, that does not only pour in money, but provides expertise than enables the capacity of the people of Myanmar to be expanded.

Secondly, I hope that the international community, through the United Nations, through member states such as the United Kingdom, could encourage the new government in Myanmar to invite the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief to visit the country, to meet with different religious groups, and to assist the new government in addressing this crucial area of human rights.

Thirdly, support initiatives that promote inter-faith dialogue, both at a leadership level and a grassroots community level, and support the efforts of Buddhists who themselves are trying to counter hatred and intolerance and ensure that the true message of Buddhism, of ‘Metta’ and ‘Karuna’, is heard. Perhaps it is time for the UN, together with the EU, the US, Canada, Australia, ASEAN, to hold an international conference in Myanmar, to bring together international experts with Myanmar civil society, political actors and religious leaders, to focus on how to protect religious freedom and promote inter-religious harmony.

Fourthly, urge the new government to take action to prevent hate speech and incitement of violence, to bring the perpetrators of hatred and violence to justice, and demonstrate moral leadership, with Aung San Suu Kyi and other NLD leaders personally and specifically speaking out against prejudice and hatred, and challenging the extreme nationalist narrative. I hope you will help her and her government take practical steps to combat hate speech and incitement to violence.

Fifthly, urge the new government not to implement the four laws on race and religion.

And finally – the situation in Rakhine state, while not by any means the only aspect of religious intolerance in Myanmar, is the most acute, most severe and most difficult to resolve. It is an intolerable situation, and one which cannot be allowed to remain unresolved. Whatever the perspectives – and there are, within my country, a variety of perspectives – about the origin of the Rohingya people, there cannot be doubt that those who have lived in Myanmar for generations have a right to be regarded as citizens, and that all of them deserve to be treated humanely and in accordance with international human rights. Seeing thousands of people living in dire, inhumane conditions in camps; seeing the segregation, the apartheid, that has been established in Sittwe; seeing thousands risk their lives at sea to escape these deplorable and unbearable conditions – this is not a basis for a stable, peaceful future for my country. I therefore urge the international community to encourage the new government to consider four practical steps to address the crisis in Rakhine. Take action to prevent hate speech; ensure humanitarian access for all those, on both sides of the conflict, who have been displaced by immediately lifting all restrictions on the operations of international aid agencies and devoting more government resources to assisting IDPs and isolated villagers; reform or repeal the 1982 Citizenship Law, because the lack of full citizenship lies at the root of most of the discrimination faced by the Rohingya; and finally, establish a credible independent investigation with international experts to investigate the causes of the crisis in Rakhine state, and propose action.

In all of this, where is the Catholic Church in Myanmar? I can tell you with confidence that, at least until now, we are where the government is not. We are in the slums; we are in the camps for internally displaced people; we are working with our friends in the Buddhist and Muslim communities to promote inter-faith harmony; we are providing education, health care and livelihoods; we are advocating for our people. And thanks to the support of organisations like CSW and ACN, we are able to do this. But we too face limitations. For fifty years, Church schools have been closed, after Ne Win expelled missionaries and seized Church property. And so today I say to the Government of Myanmar: give us back our schools, and allow us to contribute to educating our people.