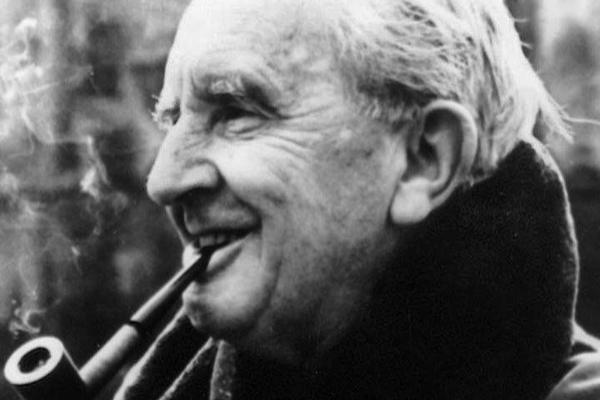

In a thought provoking essay Professor Joseph Loconte examines the events and influences which were the backdrop as JRR Tolkien composed The Lord of the Rings. The parallels between what was happening in Finland, as he constructed his epic story, and what is happening today in Ukraine 🇺🇦 are striking

Wall Street Journal: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lesson About Evil for Our Time

June 10, 2022

By Joseph Loconte

When the Soviet Union sent half a million troops into Finland on Nov. 30, 1939, J.R.R. Tolkien was sharing a glass of gin with his friend C.S. Lewis and reading him a chapter from his new story about hobbits, “The Lord of the Rings.”

It was the 19th-century Finnish epic, “The Kalevala,” that so impressed Tolkien as a young man and helped to inspire his own story. A collection of ancient songs and myths, “The Kalevala” gave the Finnish people a history and a cultural tradition—a national identity—of their own. And it is credited with helping the Finns to break away from Russian rule during World War I.

It seems likely that Finland’s fierce resistance to Russian aggression during World War II also worked on Tolkien’s imagination when he turned again to writing “The Lord of the Rings.” Not unlike the Ukrainians today, the Finns frustrated Russian plans for a quick victory. Moreover, the emergence of totalitarian regimes in Moscow and Berlin shattered European illusions about the preservation of peace in the face of evil—a theme that animates Tolkien’s mythology about the struggle for Middle-earth.

Tolkien was teaching at Oxford in 1933 when students at the Oxford Union Society approved the motion: “This House will under no circumstances fight for its King and country.” It was a shock to the political establishment. And it was a bad omen: Adolf Hitler had just become chancellor of Germany and was drawing up secret plans for remilitarization.

Tolkien began writing “The Lord of the Rings” in 1936, the same year Germany occupied the Rhineland and intervened on behalf of the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. In his introduction to the Shire and its inhabitants, Tolkien might well have been describing isolationist England under Neville Chamberlain: “And there in that pleasant corner of the world they plied their well-ordered business of living, and they heeded less and less the world outside where dark things moved, until they came to think that peace and plenty were the rule in Middle-earth and the right of sensible folk.”

A combat veteran of World War I, Tolkien watched with dread the rise of ideologies unleashed in the war’s aftermath: communism, fascism, Nazism and eugenics. Almost as soon as he began writing “The Lord of the Rings,” it took on adult themes not found in “The Hobbit.” Although Tolkien denied that his work was allegorical, he acknowledged in a 1938 letter to his publisher that his new story “was becoming more terrifying than the Hobbit. . . . The darkness of the present days has had some effect on it.”

Less than a year later, Britain was at war with Nazi Germany, its policy of appeasement in tatters. As Gandalf the Wizard explains to Frodo Baggins: “Always after a defeat and a respite, the Shadow takes another shape and grows again.” Or, as Elrond, the Lord of Rivendell, intones, “And the Elves deemed that evil was ended forever, and it was not so.”

Tolkien’s epic story embodies a moral tradition known as Christian realism: a belief in the existence of evil and in the obligation to resist it. We can hope that Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine will prod leaders in Europe and the U.S. to recover this outlook.

In Tolkien’s world, indifference to the evil of Mordor is portrayed as an evasion that can only result in catastrophe. Ending a decades-long policy of nonalignment, the Finnish parliament recently approved a plan to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—a turnabout that brings to mind a warning from Gildor the elf to the Shire: “The wide world is all about you: you can fence yourselves in, but you cannot forever fence it out.”

As a writer of fantasy, Tolkien has been accused of escapism. In fact, he used the language of myth not to escape the world but to suggest how humble, ordinary people—the hobbits—could confront with courage the sorrows, temptations and dangers of this world. In his review of “The Lord of the Rings,” Lewis wrote, “As we read, we find ourselves sharing their burden; when we have finished, we return to our own life not relaxed, but fortified.”

When Britain was thrust into the most destructive conflict in human history, Tolkien reached for an older literary tradition to find strength and resilience. He sought to give the English people what “The Kalevala” had given the Finns. The result was a war story, wrapped in myth, that teaches fundamentals about the human condition: harsh realities about the will to power and the virtues needed to stand against it.

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.