University of Oxford’s Regius Professor Nigel Biggar says that “Popular support for physician-assisted suicide declines dramatically from 73% to 43% when informed of the risks and the views of medical professionals…”

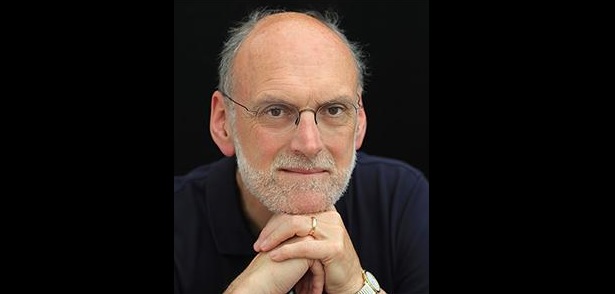

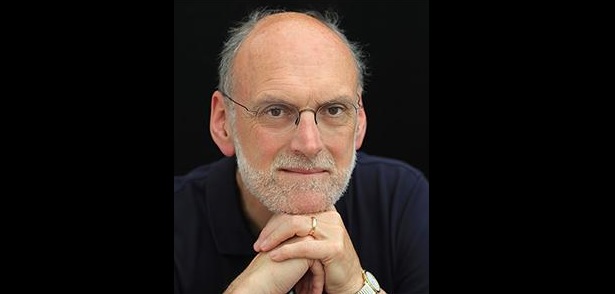

For 18 years David Alton was a Member of the House of Commons and today he is an Independent Crossbench Life Peer in the UK House of Lords.

Social Media

Site Search

Recent Posts

£1 Trillion – Raised In Parliament Today. The Cost of Reparations In Ukraine and Bringing To Justice Those Responsible.

https://youtu.be/xlEfrgwELvc Alongside the...

Stop Perpetrators Getting Away With Genocide – Public Letter sent to the UK Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary on the Genocide Determination Bill 2023-24. The letter was published this morning, 17 April 2024, 06:00 am UK time.

Stop Perpetrators Getting Away With Genocide -...