The Financial Times: Protest granny ‘prepared to die’ for Hong Kong’s freedoms

Protest granny ‘prepared to die’ for Hong Kong’s freedoms

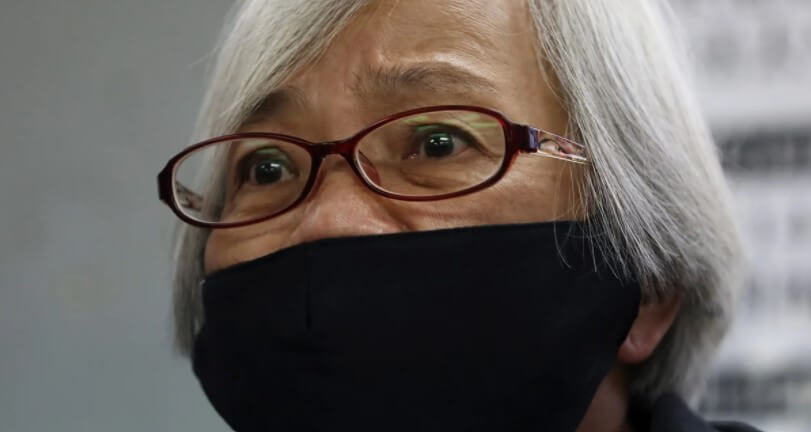

Alexandra Wong, known for waving union jack at 2019 protests, returns after arrest in mainland China

‘Grandma Wong’ waves the union jack during a demonstration outside Hong Kong’s government headquarters in 2019

On Christmas Eve, police were deployed across Hong Kong to snuff out rumoured anti-government protests. But despite the heavy security presence, one woman stood alone: 64-year-old Alexandra Wong. “Grandma Wong”, as younger activists affectionately call her, was a regular sight during last year’s demonstrations, where she unfurled a giant union. For Ms Wong, the flag — which is despised by the Chinese Communist party as representing British colonial rule in Hong Kong — was the ultimate symbol of defiance. Authorities ran out of patience in August 2019 and detained her while she was commuting to her home in Shenzhen across the border in mainland China.

After a 14-month absence, Ms Wong is back and protesting again in Hong Kong, as outspoken as ever despite a crackdown on dissent under a national security law Beijing imposed on the territory in June. Although less well known abroad than other protest figures such as activist Joshua Wong or dissident media tycoon Jimmy Lai, Ms Wong’s supporters say that few better represent the bravery and resilience of the territory’s pro-democracy movement.

Some have even spoken of nominating her for a Nobel Peace Prize. “Grandma Wong is an inspiration to generations of pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong,” said Lord Alton of Liverpool, a member of the group backing the Nobel Prize campaign. I don’t want to leave Hong Kong. Hong Kong needs me Alexandra Wong Ms Wong told the Financial Times in an interview that she feared Beijing was bent on suppressing the high degree of civil, legal and political freedom promised to the Asian financial centre on its handover to China from the UK in 1997. “I am prepared to die,” said Ms Wong, who is now living in a hotel in Hong Kong. “They will oppress us if we don’t protest and we will lose more freedoms.”

A diminutive figure with a mop of grey hair, the retired accountant became a full-time protester during the territory’s first large pro-democracy protests, the 2014 Umbrella Movement, when demonstrators occupied central Hong Kong to demand universal suffrage. When protests erupted again last year, over a proposed extradition law to mainland China, Ms Wong became a regular fixture, often getting caught up in skirmishes between protesters and police. Her signature union jack was intended to express her thanks to the former British colonial government for establishing rule of law and an education system in the territory, she said. But the banner also attracted the attention of Chinese authorities.

After her arrest in mainland China, she was held for 45 days and interrogated over her involvement in the protests and her activist contacts. Ms Wong recalls sleepless nights in a cell lying on a single platform with 16 women shoulder-to-shoulder under bright lights. The conditions tipped her into a deep depression. “I wanted to kill myself,” she said. Then followed a patriotic “re-education” trip to the north-western Chinese province of Shaanxi, where she was forced to sing Communist party songs and wave a Chinese flag. Ms Wong was eventually released on bail after being charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”, a crime often used to punish activists and political dissidents.

She was permitted to return to Hong Kong in October and, despite official warnings from mainland authorities, resumed protesting. Shenzhen’s Public Security Bureau did not reply to a request for comment. Apart from arresting activists, the Hong Kong government has purged the legislature, civil service and schools of critics. The national security law carries penalties of up to life imprisonment for crimes such as subversion, collusion with foreign forces and terrorism. Authorities maintain the crackdown is necessary to protect national security and curb last year’s protest movement, which began peacefully but grew into citywide clashes between police and protesters. Ms Wong is also under pressure. Pro-Beijing newspaper Wen Wei Po has called her the “crazy colonial lover”. Since her return to the city, Ms Wong has been charged with assault for allegedly pushing a female security guard at a Hong Kong court last year.

Unmarried and with no children of her own, Ms Wong said she viewed Hong Kong’s young protesters as her grandchildren and urged them to flee to the UK or Canada and continue demonstrating. “The more people who get away, the better,” she said. Since returning to Hong Kong, Ms Wong has attended court hearings to support young demonstrators and mounted one-person protests outside the city’s legislature and the office of Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive. She admitted to being fearful about the new national security law but said she felt safer in Hong Kong, where the media could still report on her whereabouts. “I don’t want to leave Hong Kong. Hong Kong needs me,” she said. Ms Wong has also replaced her trademark union jack, which was confiscated by mainland Chinese authorities, with a tote bag emblazoned with a huge version of the British flag. She uses it to carry her protest paraphernalia.