Historic House of Lords Vote on All-Party Amendment on Genocide Determination passes by a Majority of 126. Now Members of the Commons have the chance to say no to trade deals with States credibly accused of Genocide.

To read the full debate on the Human Rights and Genocide Amendment to the Trade Bill go to

Speeches by Lord Alton of Liverpool

7.10 pm

Sitting suspended.7.41pmLord Alton of Liverpool (CB)Sharethis specific contribution

My Lords, the Government may be concerned to see noble Lords return from that intermission invigorated and fortified for the remainder of the evening that lies ahead. I start by congratulating the noble Lord, Lord Collins, on the way in which he introduced his important amendment, to which I am a signatory, and the thoughtful way he expressed the reasons that lie behind it. I will not say it is a pleasure, because the issues we are discussing are hardly that, but I am always glad to be able to stand with the noble Lord, specifically when we deal with atrocity crimes and human rights, and tonight is no exception. I support Amendments 8 and 10 and the consequential new Schedule, which is linked to Amendment 10. I am a signatory to those amendments, proposed by the noble Lords, Lord Collins, and Lord Blencathra, from whom the House will hear in due course.

In his well-judged opening speech, the noble Lord, Lord Collins, explained that the amendments focus on our duty to examine the human rights records of trading partners. Later, as the noble Lord said, the House will debate Amendment 9, an all-party amendment in my name, which is more narrowly drawn, specifically targeting trade agreements with states accused of committing genocide, and putting in place a judicial mechanism to break the vicious circle that leads to inaction as genocides emerge.

Like Amendment 9, Amendment 10 in the name of the noble Lord, Lord Blencathra, also provides a judicial mechanism to enable a wholly independent judge to assess human rights violations wider than genocide. Amendment 8, in the name of the noble Lord, Lord Collins, provides the opportunity, through risk assessment, parliamentary scrutiny and an annual report to Parliament, to look at serious violations of human rights, including torture and servitude. I should declare that I am a trustee of a charity, the Arise Foundation, which combats modern-day slavery, and a patron of the Coalition for Genocide Response.

These amendments are not dependent on one another, or mutually exclusive. Taken together, they could provide a combination of oversight and pressure from within and outside Parliament, providing belt and braces. If enacted, they will enable us to redefine our willingness to trade with those responsible for egregious crimes against humanity—an opportunity which I flagged at Second Reading. Subsequently, on 29 September, during day 1 of our Committee proceedings, I moved Amendment 33, an all-party amendment which I described as an attempt to open a debate around three things: first, doing business with regimes which commit serious breaches of human rights; secondly, the overreliance on non-democratic countries in the provision of our Toggle showing location ofColumn 1037national infrastructure; and thirdly, the role that Parliament and the judicial authorities might have in informing those questions. On 13 October, the fifth day of Committee, I moved Amendments 68 and 76A on the narrower point of trading with countries judged by the High Court of England and Wales to be complicit in genocide.7.45pm

For the sake of completeness, I shall also refer to my Amendment 5, which I moved on 29 June on Report of the telecommunications infrastructure Bill, in which a number of noble Lords present tonight, in the House and online, participated. Despite a range of powerful speeches from all sides during that debate, the movers agreed to the Government’s request not to press the amendment to a vote following an undertaking by the Minister, the noble Baroness, Lady Barran, that the Government would engage with them and return at Third Reading with an amendment of their own. Several cross-departmental meetings were subsequently held but the Government were unable to table a Third Reading amendment, and indeed that Bill has disappeared into the long grass.

I am deeply disappointed that the Government have not used the Trade Bill to resolve this issue. I echo what the noble Lord, Lord Collins, said about that missed opportunity for the Government to bring forward an amendment that they themselves had crafted. The House needs to understand that, despite the willingness of noble Lords to engage with Ministers, the principle that serious human rights violations and even the crime of genocide should determine our trading relationships has not been accepted by the Government. Sadly, like Banquo’s ghost, a government amendment is this evening absent from the Room—probably having suffered the same fate as Banquo—which is why these amendments are on the Order Paper.

It should be clearly stated that Amendments 8, 10 and 9 make no mention of any particular country that might fall foul of these provisions. The movers are clear that these are not catch-all amendments but are carefully constructed to assess both the seriousness of such violations and the direction of travel of the country concerned. I could of course provide the House with a Baedeker’s guide to countries where human rights violations occur, but that is not the point of these amendments.

However, in imagining the circumstances in which such amendments might come into play, I will give the House just one hypothetical example of a country whose human rights record should be scrutinised and would be likely to be affected by these amendments. In that context, I refer to my role as vice-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Uighurs and the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Hong Kong. However, I add that the example is merely illustrative.

Forty years ago, as a young Member of another place, I had the opportunity in the early 1980s to travel in China. It was in the aftermath of the death of Mao Tse-Tung, whose 27-year reign of terror, which led to the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward, took the lives of tens of millions of people. Estimates of the number of people who died Toggle showing location ofColumn 1038under his regime range from 40 million to as many as 80 million, through starvation, persecution, prison labour and mass executions.

Notwithstanding the massacres in Tiananmen Square, China in the late 1980s and early 1990s—I know the noble Lord, Lord Grimstone, sometimes alludes to this himself and knows it to be true—appeared to be moving towards economic and political reform, perhaps exemplified most of all in the important “one country, two systems” pledge of the 1984 Sino-British declaration on Hong Kong. However—as we have seen with the dismantling of the Hong Kong model, the brazen arrests of pro-democracy campaigners, distinguished lawyers and opposition Members of the Legislative Council, and the emasculation of the rule of law—one-party, one-system hegemony is the order of the day. On the mainland, plurality and diversity are outlawed, made manifest by the arrest and imprisonment of dissidents, lawyers, artists, writers and religious adherents.

I have reduced what I was going to say today in the interests of time but I shall specifically mention Xinjiang, where an estimated 1 million Muslims are incarcerated in re-education and forced labour camps, subjected to brainwashing and surveillance, turned into slaves, separated from their families, sterilised and aborted and told to disown their culture and their religion—even forced to watch the destruction of their cemeteries, the desecration of their mosques and the obliteration of their identity. Professor Adrian Zenz, a German scholar, has described this as

“the largest detention of an ethnoreligious minority since World War Two”,

while a Newcastle academic describes it as

“a slow, painful, creeping genocide.”

Notwithstanding a great love of Chinese people and respect for Chinese culture, I carefully distinguish between my love of China its people and my enmity to an ideology and a system that would treat its own people in this barbaric way, brutally silencing any dissent. In considering our business and trade relations with the Chinese Communist Party, we can do little better than to consider the wise words of the noble Lord, Lord Patten of Barnes. He says that the CCP is

“a regime which regards business, as well as the state-owned enterprises, as part of the political project.”

There is an umbilical link between the CCP and the country’s companies—that is not in dispute. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute meticulously details the global expansion of 23 key Chinese technology companies and their links to the state. We know that Uighurs are used as forced labour in factories within the supply chains of at least 82 well-known global brands in the technology, clothing and automotive sectors, including Huawei, Apple, BMW, Gap, Nike, Samsung, Sony and Volkswagen. According to one report, the UK is strategically dependent on China for our supplies in 229 separate categories of goods, 57 of which service elements of our critical national infrastructure.

The deepening ideological hostility of Xi Jinping—who, as President for life, has returned to a personal dictatorship not seen since the days of Mao—his hostility to democracy, international institutions, the rule of law, and fundamental human rights, show how wrong western Toggle showing location ofColumn 1039Governments were to believe that more and more trade with the CCP was going to insure us against an ideology which despises liberal democracy and the freedoms which we associate with it. I could cite other examples of how these amendments might have application, but do not intend to weary the House with that now.

As we consider future trading partners, we have the chance to link the trade we do with the values for which we stand. The United Kingdom was one of the nations that gave the world the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the convention on the crime of genocide. Later, through the Helsinki accords, the United Kingdom and its allies knew the central importance of upholding of human rights with a patient determination that ultimately saw the collapse of the Berlin Wall. We did not achieve that by selling our souls to dictators.

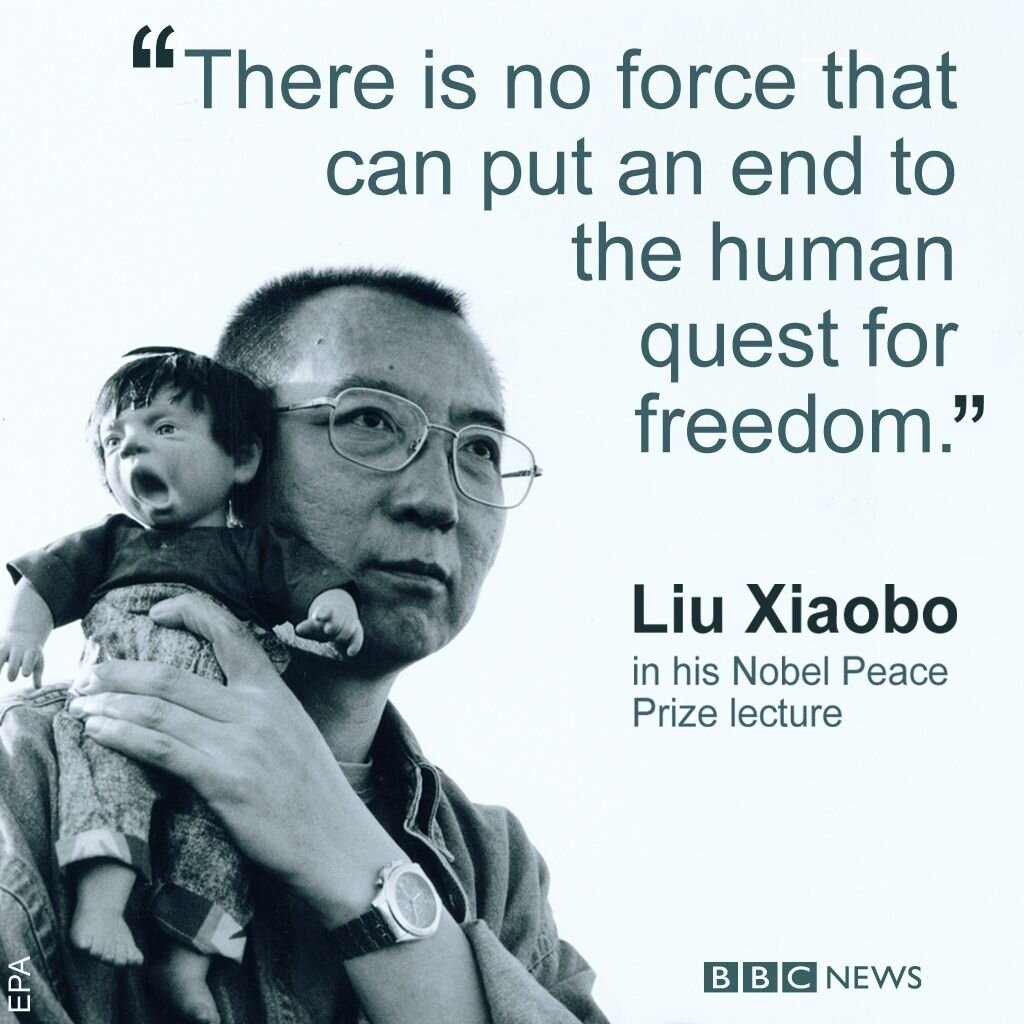

We believe in a rules-based international order and we espouse liberal democracy, the upholding of diversity, the protection of minorities and the eternal quest for freedom. Those principles enunciated in these amendments would send a signal of hope to beleaguered people in dire circumstances, but I end with what I think it will say to the Chinese Communist Party and other violators of human rights. Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese writer and dissident, and Nobel laureate, who died in 2017, after serving four prison sentences, said:

“There is no force that can put an end to the human quest for freedom.”

We owe it people such as him, the incarcerated Uighurs, the suffering Tibetans, the Falun Gong and other religious believers persecuted for their faith, to stand four-square with them in that quest. By voting for these amendments, we will demonstrate—to arrested lawyers such as Hong Kong’s Martin Lee; young jailed pro-democracy campaigners such as Andy Li, Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow; to imprisoned newspaper owner Jimmy Lai; and defiant women like the brave Grandma Wong—that we will uphold the human rights of place such as Hong Kong and Xinjiang. We will put our belief in the quest for human freedom before menacing intimidation, brutal suppression of human rights and trade based on slave labour. It is for those reasons that these amendments are so important, and I will have no hesitation in voting for them tonight.

=====================

9.05pmThe Deputy Speaker (Lord Bates) (Con)Sharethis specific contribution

My Lords, we now come to the group beginning with Amendment 9. I remind noble Lords that Members other than the mover and the Minister may speak only once and that short questions of elucidation are discouraged. Anyone wishing to press this or anything else in this group to a Division should make that clear in debate.

Amendment 9

Moved byLord Alton of Liverpool Sharethis specific contribution

9: After Clause 2, insert the following new Clause—

“Agreements with states accused of committing genocide

(1) International bilateral trade agreements are revoked if the High Court of England and Wales makes a preliminary determination that they should be revoked on the ground that another signatory to the relevant agreement represents a state which has committed genocide under Article II of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, following an application to revoke an international bilateral trade agreement on this ground from a person or group of persons belonging to a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, or an organisation representing such a group, which has been the subject of that genocide. Toggle showing location ofColumn 1059(2) This section applies to genocides which occur after this section comes into force, and to those considered by the High Court to have been ongoing at the time of its coming into force.”Lord Alton of Liverpool (CB)Sharethis specific contribution

My Lords, the House has already heard some of the arguments explored in the preceding group of amendments. The House will be relieved to know that I will not rehearse them all again.

Amendment 9 straightforwardly asks the House to give the High Court of England and Wales the opportunity to make a predetermination of genocide if it believes that the evidence substantiates the high threshold set out in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, to which the United Kingdom is a signatory. I am grateful to the noble Baroness, Lady Kennedy of The Shaws, my noble friend Lady Falkner of Margravine and the noble Lord, Lord Forsyth—the other sponsors of this all-party amendment—to Peers from all parts of the House and to the Coalition for Genocide Response, notably its co-founders, Luke de Pulford and Ewelina Ochab.

During the preceding debate we heard three things about Amendment 9 which I would like to deal with immediately. The first was from the Minister, the noble Lord, Lord Grimstone. He has now retreated to the Back Benches after the exhaustion of the last few hours and we welcome the noble Viscount to his place to answer this debate. The noble Lord, Lord Grimstone, talked about the separation of powers. I remind the House that in the case of genocide, whenever the Government speak on this issue in this House, we always say that it is a matter for the courts. This is the same Government. They say that there is a separation of power and indeed, recently said that the recognition of genocide

“is a matter for judicial decision, rather than for Governments or non-judicial bodies.”—[Official Report, 13/10/20; col. 1042.]

I gently say to the Minister, and the noble Lord, Lord Lansley, that the Government’s position is that the courts make the determination about genocide. That is not to say that Parliament should not have a view about these things—I agree with what the noble Lord, Lord Collins, said earlier about the role of the courts. I would also say to the noble Baroness, Lady Noakes, who has left the Back Benches but may be viewing from elsewhere, that this is not about virtue signalling. This is about virtuous behaviour. If we cannot stand up on the crime of genocide and say that once evidence has been placed before the courts, it is shown to be credible and they make a predetermination, we will not then, in those circumstances, stop trading with that country, in what circumstances would we do so? There is a clear issue here on this narrow point of genocide. That is why this amendment is different from those that have preceded it. It is about one question: the crime above all crimes. I realise that some noble Lords who would not have been able to vote on the earlier amendment support this amendment because it is so carefully constructed and defined.

Three speeches were made in Committee that explain the thinking behind this amendment very well. The noble Lord, Lord Stevenson of Balmacara, rightly said that enabling the UK High Court to make legal Toggle showing location ofColumn 1060determinations on genocide is preferable to other legal avenues. Pursuing such claims through international courts has proven ineffective. The amendment provides a respected means to assessing genocide, allowing the UK to live up to its legal commitments on genocide. He is right. The noble Baroness, Lady Northover, added that future trade deals may not be subject to parliamentary scrutiny, so it is imperative that the Government decide now to rule out deals with perpetrators of genocide. Not for the first time, the noble Baroness is right.

My noble and learned friend Lord Hope of Craighead, who has a lifetime of experience in the highest reaches of the law, said in a hugely important speech in Committee that there is inadequacy in the judicial architecture currently in place. In comparing the genocide convention with the convention on torture, he said:

“The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide now seems, with hindsight, to be a deplorably weak instrument for dealing with the challenges we face today … we can now see, in today’s world, how ineffective and perhaps naive this relatively simple convention is.”

The noble and learned Lord said that the amendment would

“allow for due process in a hearing in full accordance with the rule of law.”

It would “achieve its object” and result

“in a fully reasoned judgment by one of our judges. That is its strength, as a finding by a judge in proceedings of this kind in the applicant’s favour will carry real weight, quite apart from the effect it will have on the relevant agreement.”—[Official Report, 13/10/20; cols. 1037-38.]

He said that the route we have chosen in this amendment has his “full support” and would be “a big step forward”.

Just three weeks ago, we marked 75 years since the Nuremberg trials. Sir Hartley Shawcross, later a Member of your Lordships’ House, was the Labour Member of Parliament for St Helens and the lead British prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes tribunal. In his closing speech at Nuremburg, Shawcross remarked that when

“some individual is killed, the murder becomes a sensation, our compassion is aroused, nor do we rest until the criminal is punished and the rule of law is vindicated. Shall we do less when not one but … 12 million men, women, and children, are done to death? Not in battle, not in passion, but in the cold, calculated, deliberate attempt to destroy nations and races”.

Shawcross reminded his generation that such tyranny and brutality, such genocides, could only be resisted in the future not by

“military alliances, but … firmly … in the rule of law.”

Yet we all know how regularly such horrors have recurred while the law we put in place in 1948 has been honoured only in its breach.

I will unpack the vicious circle that the amendment seeks to break. Over the past 20 years, I have raised the issue of genocide on 300 occasions in speeches or Parliamentary Questions in your Lordships’ House. As recently as 5 November, I asked the Government whether they intended to follow the example of Canadian parliamentarians in designating actions by the Government of China against their Uighur population to be a genocide, and what plans they had, if any, to enable an appropriate judicial authority to consider the same evidence and to reach a determination on this matter.Toggle showing location ofColumn 1061

In reply, I was given the usual circular argument that the Government’s policy is not to make such determinations themselves but—and I say this gently to the noble Lord, Lord Lansley—to leave it to the courts, knowing that the International Criminal Court would require a referral from the Security Council and that, in this case, China would veto any attempt to hold it to account by the International Criminal Court.

I also say gently to my good and noble friend Lord Sandwich, responding to his remarks in the earlier group of amendments, that this amendment does not seek to carry out criminal prosecutions in the High Court of England and Wales. If it did, it would have to overcome all sorts of obstacles to bring about a prosecution. This amendment seeks to establish whether there is sufficient evidence available to accurately describe a genocide. We heard some of it from the noble Baroness, Lady Bennett of Manor Castle, in her intervention on the last group. Is there sufficient evidence for a predetermination to be made? That is the point: this is not about a criminal prosecution; it is about whether there is evidence that can be established in the High Court of England and Wales.9.15pm

Before lockdown, I went to northern Iraq. I met Yazidi and Christian leaders who told me, “What happened to us was way beyond imagination”.

It is not beyond our imagination—quite the reverse. In March 2016, my noble friend Lady Cox, the noble Baroness, Lady Kennedy of The Shaws, the noble Lord, Lord Forsyth, and I specifically moved an amendment calling for the evidence we presented during that debate—of horrific genocidal acts being carried out against Yazidis, Christians and other minorities—to be laid before the High Court and for a judge to determine whether those atrocities were part of a genocide, which would, of course, have required an appropriate response from the Government. The Government opposed the amendment and I hardly need remind the House of what occurred.

During my visit to northern Iraq, I met some of the families whose girls had been abducted, raped and enslaved. Some of them are still refugees, having seen neighbours slaughtered and homes confiscated. In every case that I have ever raised, going right back for 20 years—20 years ago, I raised what was happening at the hands of the Burmese military in the Karen State, which I had gone into illegally, and was told that it was not a matter we could deal with here—I have always received the same reply. I remind the House of what the noble Lord, Lord Ahmad, said: that the recognition of genocide

“is a matter for judicial decision … rather than for governments or non-judicial bodies.”

Yet, as my noble and learned friend told us in Committee, the international judicial system is not functioning as intended.

This is not about ceding power from Parliament to the courts, as the noble Lord, Lord Lansley, was right to caution us about. This is not about the widespread ceding of powers; this is about a very narrow area. This is about genocide and a policy that is already the position of the Government. It is depoliticising a decision that Governments of all persuasions have hesitated to make. Limiting the clause to genocide is also proportionate. Toggle showing location ofColumn 1062There can be no clearer statement that the United Kingdom places its values above trade than making it clear that we are not content to strike deals with genocidal states.

Let me finish my remarks by recalling again the challenge laid down 75 years ago at Nuremberg by Sir Hartley Shawcross. For 70 years, we have failed to recognise our wholly inadequate response to those challenges. Tonight, we have a chance to put that right. I intend to ask the House to vote on this amendment, unless the Government are prepared to say that they will come forward with an amendment at Third Reading to deal specifically with the issue of genocide or will do so in another place.

No doubt we will be told, as we so often are, that this is the wrong amendment, that it is technically defective, that it is the wrong Bill, or that it is the wrong time. We are always told those things. It is always the wrong time; it is always the wrong Bill. The amendments are never perfect, but the whole point is that, week in, week out, I have been urging the Government to sit down with us and with some of the most celebrated lawyers in this country, who are esteemed in their knowledge of human rights law and who, through the Coalition for Genocide Response, circulated as recently as this morning a long brief setting out why this is a viable amendment and why any refinements that are needed can easily be rectified if there is good will on the part of the Government.

By sending this amendment to the House of Commons, where I know that it has support on both sides of the Chamber—notably from the former leader of the Conservative Party, Sir Iain Duncan Smith—I know that we will ensure that something good will come out of our debate tonight and out of the effort that so many noble Lords have put into this issue. It will give the other House a chance to engage and remedy any deficiencies in drafting. Tonight, we should not hesitate in affirming the principle that we will not trade with countries judged by our High Court to be mired in genocide. I beg to move.

==============

Lord Alton of Liverpool (CB)Sharethis specific contribution

My Lords, I am grateful to the noble Viscount for his response to the debate. He would not expect me, though, to accept the tenor of his arguments, nor would the House expect me to speak at any length at the conclusion of this debate, because I know, as the noble Baroness, Lady Meacher, was right to remind us, that we would like to move to a vote.

Let me make just two points. Anyone who doubts the point of the House of Lords should read the speeches tomorrow in Hansard, because it has been a remarkable debate on all sides. Good, constructive points have been made, and people have quite rightly said no amendment is going to be perfect and any amendment can be refined and improved. That is the purpose of this place—it is the point of our existence. If we send this amendment to the House of Commons, it can continue to be worked on and those issues can easily be addressed.

During the debate, a number of noble Lords, including the noble Baroness, Lady Smith, and the noble Lord, Lord Polak, mentioned Rwanda. I visited the genocide sites in Rwanda; I went to a place called Murambi, where 56,000 people had been killed. I saw the skeletons of pregnant women with their children in what had been a college but had been turned into a memorial for victims of that violence. The noble Lord, Lord Hague of Richmond, as William Hague, our Foreign Secretary, spoke at the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, and he said:

“It is not enough to remember; we have a responsibility to act.”

It is not enough to remember. We have a responsibility to act.

During the Second World War, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a renowned theologian, defied Hitler and the Reich. He was sentenced to death and executed. He famously said:

“Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act.”

Now is the time to act.

I would like to test the opinion of the House.

Columns 1088 – 1090is located hereDivision 4Division conducted remotely on Amendment 9Content287Not Content161Amendment 9 agreed.Held on 7 December 2020 at 11.01pm11.13pm