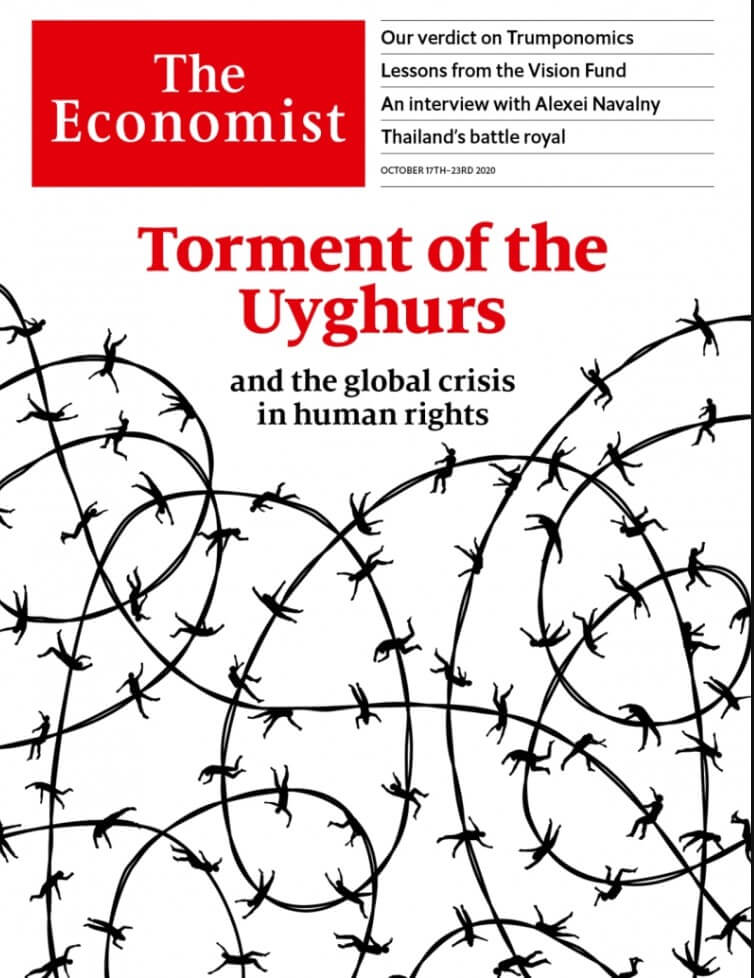

Xinjiang and the world The persecution of the Uyghurs is a crime against humanity

It is also the gravest example of a worldwide attack on human rights – The Economist

THE FIRST stories from Xinjiang were hard to believe. Surely the Chinese government was not running a gulag for Muslims? Surely Uyghurs were not being branded “extremists” and locked up simply for praying in public or growing long beards? Yet, as we report in this week’s China section (see article), the evidence of a campaign against the Uyghurs at home and abroad becomes more shocking with each scouring of the satellite evidence, each leak of official documents and each survivor’s pitiful account.

In 2018 the government pivoted from denying the camps’ existence to calling them “vocational education and training centres”—a kindly effort to help backward people gain marketable skills. The world should instead heed Uyghur victims of China’s coercive indoctrination. Month after month, inmates say, they are drilled to renounce extremism and put their faith in “Xi Jinping Thought” rather than the Koran. One told us that guards ask prisoners if there is a God, and beat those who say there is. And the camps are only part of a vast system of social control.

China’s 12m Uyghurs are a small, disaffected minority. Their Turkic language is distant from Chinese. They are mostly Muslim. A tiny handful have carried out terrorist attacks, including a bombing in a market in 2014 that left 43 people dead. No terrorist incidents have occurred since 2017: proof, the government says, that tighter security and anti-extremism classes have made Xinjiang safe again. That is one way of putting it. Another is that, rather than catching the violent few, the government has in effect put all Uyghurs into an open-air prison. The aim appears to be to crush the spirit of an entire people.

Even those outside the camps have to attend indoctrination sessions. Any who fail to gush about China’s president risk internment. Families must watch other families, and report suspicious behaviour. New evidence suggests that hundreds of thousands of Uyghur children may have been separated from one or both detained parents. Many of these temporary orphans are in boarding schools, where they are punished for speaking their own language. Party cadres, usually Han Chinese, are stationed in Uyghur homes, a policy known as “becoming kin”.

Rules against having too many children are strictly enforced on Uyghur women; some are sterilised. Official data show that in two prefectures the Uyghur birth rate fell by more than 60% from 2015 to 2018. Uyghur women are urged to marry Han Chinese men and rewarded if they do with a flat, a job or even a relative being spared the camps. Intimidation extends beyond China’s borders. Because all contact with the outside world is deemed suspect, Uyghurs abroad fear calling home lest they cause a loved one to be arrested, as a harrowing report in 1843, our sister magazine, describes (see article).

The persecution of the Uyghurs is a crime against humanity: it entails the forced transfer of people, the imprisonment of an identifiable group and the disappearance of individuals. Systematically imposed by a government, it is the most extensive violation in the world today of the principle that individuals have a right to liberty and dignity simply because they are people.

China’s ruling party has no truck with this concept of individual rights. It claims legitimacy from its record of providing stability and economic growth to the many. Its appeal to the majority may well command popular support. Accurate polling is all but impossible in a dictatorship, and censorship insulates ordinary Chinese from the truth about their rulers. But many Chinese people clearly do back their government, especially since to object is deemed unpatriotic (see article). Awkward minorities, such as Tibetans and Uyghurs, have no protection in such a system. Unbound by notions of individual rights, the regime has been determined to terrorise them into submission and force them to assimilate into the dominant Han culture.

China lies at the extreme of a worrying trend. Globally, democracy and human rights are in retreat. Although this began before covid-19, 80 countries have regressed since the pandemic began and only Malawi has improved, says Freedom House, a think-tank. Many people, when scared, yearn to be led to safety by a strong ruler. The virus offers governments an excuse to seize emergency powers and ban protests (see article).

Abusive rulers often rally the majority against a minority. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, espouses an aggressive Hindu nationalism and treats India’s Muslims as if they were not really citizens. For this, he earns stellar approval ratings. So does Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, who urges the murder of criminal suspects. Hungary’s prime minister crushes democratic institutions and says his opponents are part of a Jewish plot. Brazil’s president celebrates torture and claims that his foreign critics want to colonise the Amazon. In Thailand the king is turning a constitutional monarchy into an absolute one (see article).

How can those who value liberty resist? Human rights are universal, but many associate them with the West. So when the West’s reputation took a battering, after the financial crisis of 2007-08 and the botched war in Iraq, respect for human rights did, too. Although America has imposed targeted sanctions over the Uyghurs, the suspicion that Western preaching was hypocritical has grown under Donald Trump. A transactional president, he has argued that national sovereignty should come first—and not only for America. That suits China just fine. It is working in international forums to redefine human rights as being about subsistence and development, not individual dignity and freedom. This week, along with Russia, it was elected to the UN Human Rights Council.

Start in Xinjiang

Resistance to the erosion of human rights should begin with the Uyghurs. If liberals say nothing about today’s single worst violation outside a war zone, how can anyone believe their criticism of other, lesser crimes? Activists should expose and document abuse. Writers and artists can say why human dignity is precious. Companies can refuse to collude. There is talk of boycotts—including, even, of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

Ultimately, governments will need to act. They should offer asylum to Uyghurs and, like America, slap targeted sanctions on abusive officials and ban goods made with forced Uyghur labour. They should speak up, too. China’s regime is not impervious to shame. If it were proud of its harsh actions in Xinjiang, it would not try to hide them. Nor would it lean on smaller countries to sign statements endorsing its policies there. As the scale of the horror emerges, its propaganda has grown less effective: 15 majority-Muslim countries that had signed such statements have changed their mind. China’s image has grown darker in many countries in recent years, polls suggest: 86% of Japanese and 85% of Swedes now have an unfavourable view of the country. For a government that seeks to project soft power, this is a worry.

Some say the West would lose too much by lecturing about human rights—China won’t change, and the acrimony will stymie talks about trade, pandemics and climate change. True, keeping human rights separate from such things is impossible, and China will try to convince other countries that moral candour will cause them economic harm. Nonetheless, liberal democracies have an obligation to call a gulag a gulag. In an age of growing global competition, that is what makes them different. If they fail to stand up for liberal values they should not be surprised if others do not respect them, either. ■

Dig deeper

How Xinjiang’s gulag tears families apart

From 1843 magazine: “If I speak out, they will torture my family”: voices of Uyghurs in exile

Thailand’s king seeks to bring back absolute monarchy

The pandemic has eroded democracy and respect for human rights

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition under the headline “Torment of the Uyghurs”

=========================================================================

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE

For Immediate Release October 16, 2020

Special Online Briefing

Assistant Secretary Robert Destro

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor

And Ambassador-at-Large John Cotton Richmond

Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons

October 16, 2020

The Brussels Hub

Moderator: Hello. I’d like to welcome journalists to today’s virtual press briefing with Robert Destro, Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, and John Cotton Richmond, Ambassador-at-Large to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons.

And with that, let’s get started. Assistant Secretary Destro and Ambassador Richmond, thank you so much for joining us today. I’ll turn it over to you for your opening remarks.

Ambassador Richmond: Wonderful. Thank you so much for taking time to talk about this important issue.

The United States has made the global fight against human trafficking a policy priority across government agencies. Human trafficking is, of course, an umbrella term that includes both sex trafficking and forced labor. And when we think about human trafficking, we normally think of individual criminals, gangs, or networks of conspirators. In these cases, we rely upon governments to enforce laws to stop traffickers and protect victims. But what do we do when the government itself is acting as the trafficker? Far too often, governments have a policy or pattern of trafficking people. And in the 2020 Trafficking in Persons Report published by the U.S. State Department, the Secretary of State found that there was a government policy or pattern in 10 countries. Those 10 countries include China, along with Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma, Cuba, Eritrea, North Korea, Russia, South Sudan, and Turkmenistan.

The United States condemns the Chinese Communist Party’s egregious and widespread practice of trafficking its own people as part of its campaign of repression against Muslim Uyghurs and members of ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang and throughout China. The Chinese Communist Party has intensified its repression, arbitrarily detaining more than 1 million Uyghurs and members of other ethnic religious minority groups, subjecting them to compulsory political and ideological indoctrination and forcing many in work camps, factories, and sweat shops to labor.

Since 2017, the Chinese Communist Party has reportedly transferred many thousands of detainees forcibly from internment camps in Xinjiang to factories producing textiles, electronics, and other items in provinces throughout China where their abuse continues under the guise of poverty alleviation or vocational training programs. Although the Chinese Communist Party at various times has claimed that it began to close the internment camps and scaling this horrific program back, recent reports indicate it actually criminally charging many detainees and moving them into new or expanded, higher security prisons, and in some cases transferring them to and forcing them to work in manufacturing sites.

We’re further dismayed to learn of reports that these abuses may exist at an alarming scale in the Tibetan Autonomous Region: the forceful relocation and reeducation, quote, “vocational training and poverty alleviation,” of many thousands of Tibetans coupled with allegations of compulsory participation in vocational training programs and forced labor. We will continue to monitor this situation as we assess China’s complicity in 2020 and 2021.

As the government’s practice of forced labor continues to spread beyond Xinjiang, it is increasingly difficult for well-intentioned international companies to track exactly which products in their supply chain are made with forced labor, and if the suppliers or other entities they work with are involved in these abuses.

Meanwhile, the People’s Republic of China injects these products made with forced labor into global supply chains through its exports. And we will not allow those products to enter United States markets. U.S. companies do not want to unwittingly support forced labor, and neither do U.S. consumers. We will continue to help them connect with labor rights advocates, NGOs, governments, and others to create solutions, to call attention to forced labor abuses in China, and ensure that Beijing is not profiting from forced labor.

In 2017, the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report ranked China as Tier 3, the lowest possible tier, because of state-sanctioned forced labor. In 2020 in the TIP Report, we called upon China to abolish the arbitrary detention and forced labor of persons in internment camps and affiliated manufacturing sites in Xinjiang and other provinces immediately, and to release and pay restitution to individuals whom they detained, end forced labor in government facilities and nongovernmental facilities converted to government detention centers, and by government officials outside the penal process.

We commit to working with our government and private sector partners to ensure the Chinese Communist Party can no longer profit from its own human rights abuses, including human trafficking in the form of forced labor. We call on all nations, business, and consumers to demand global supply chains that are free from forced labor. This is an important issue because at the heart of human trafficking is the inherent right of every individual to be free.

We look forward to our discussion today. Thank you.

Moderator: Assistant Secretary Destro.

Assistant Secretary Destro: Thank you. Thank you, Ambassador Richmond. Ambassador Richmond has done a great job this morning talking about the human trafficking elements of the situation in China. My job is to talk a little bit about the shocking human rights abuses generally being perpetrated by the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang against Uyghurs, ethnic Kazakhs, ethnic Kyrgyz, and members of other minority groups. There’s also abuses are – that are going on constantly and now include forced abortions, sterilization, mass arbitrary detention, forced labor, high-technology surveillance, involuntary collection of biometric data and other genetic information.

Today, we want to focus on aspects of the campaign of repression that intersect with business and labor. There are growing reports that Beijing’s state-sponsored labor practices in Xinjiang – the CCP says that these are vocational training or, quote, “poverty alleviation programs.” But the reality is quite different. It’s clear that people are being compelled to work against their will. It’s also the case that these so-called programs frequently include transferring workers involuntarily from Xinjiang to other regions of China. These forced labor programs separate families, leaving children as young as 18 months old in state-run orphanages, boarding schools, and other indoctrination facilities while the parents are forced to work full-time under constant surveillance with little or no pay and with limited freedom of movement.

The CCP and Chinese businesses are blatantly profiting from their victims’ labor. The strategy is predicated upon low-skilled, labor-intensive industries that only require a limited amount of job training, such as textiles and garments, electrical products, shoes, and furniture. The companies take advantage of the free or low-cost forced labor of Xinjiang residents. These businesses then export their goods around the world. This puts businesses in other countries and consumers like you and me at risk of unknowingly supporting forced labor and the CCP’s human rights abuses.

So, to address this problem, the U.S. Government is launching a coordinated response against these abuses, including closing off opportunities to do business in the United States for companies that do not respect human rights, and kicking off a clean supply chain effort. Over the last several months, the U.S. Department of Commerce added dozens of commercial and government organizations to the PRC – in the PRC to their Bureau of Industry and Security Entity List. These companies provide technology that perpetrates Beijing’s campaign of repression in Xinjiang, including the development of artificial intelligence applications that allow for the high-tech surveillance of Uyghurs and other ethnic Muslim minorities. The effect being – of being on the entity list is the imposition of a license requirement on the export of U.S.-origin items to these companies.

Last month, U.S. Customs and Border Protection issued five withhold release orders on goods produced in China, four of which were directly linked to products produced in Xinjiang. These new actions are in addition to five other withhold release orders previously issued related to goods produced in China since last September. These orders prevent goods from being imported into the United States when made with forced labor. If there’s a withhold release order, that means that Customs and Border Protection will detain any shipments of goods from the company or a location named in the order, and not let those goods enter the United States, in line with U.S. customs laws.

The United States is also trying to help businesses make sure that they are not unknowingly complicit in human rights abuses in Xinjiang and other places, including the use of forced labor. In July, the U.S. Department of State, along with three other U.S. federal government agencies, issued a business advisory for U.S. businesses about the risks of having their supply chains linked to entities complicit in forced labor and other human rights abuses throughout China. We’re also helping businesses concerned that their companies’ products are being sold overseas that can be misused as a tool for human rights abuse. For example, over the last several years, we’ve seen a large rise in foreign governments such as the PRC misusing products or services with surveillance capabilities; concerning trends, including government use of spyware to target journalists and human rights advocates; and the use of DNA sequencers and facial recognition technologies to suppress human rights and human rights advocates in China and elsewhere.

Businesses in the United States and all around the world don’t want to be complicit in this type of human rights abuse, nor, I might add, do most ordinary consumers. To help minimize this risk, last month the U.S. Department of State issued guidance to help U.S. businesses evaluate the human rights impacts of their products or services with surveillance capabilities and to understand the risks associated with engaging in transactions with various government end users. The guidance also recommends a human rights safeguard if the U.S. business considered proceeding with the transaction, developing a grievance mechanism, or publicly reporting on sales practices.

We all have a role to play in stopping business rights – business-related human rights abuses, including forced labor. Businesses should conduct human rights due diligence on their supply chains and business partners before entering into contracts. Consumers should speak up with concerns about the money they spend buying apparel, electronics, or food going into the pockets of human rights abusers. And governments should engage with companies and restrict imports of goods made with forced labor.

With that, I’m going to stop. Thank you for your attention this morning, today, and we look forward to your questions.

Moderator: Wonderful. Thank you very much. We’ll now turn to the question and answer portion of today’s briefing.

So our first question goes to Bakytnur from Channel 31 in Kazakhstan, and Bakytnur asks: “On September 26th, Chinese President Xi called the Xinjiang policy, and I quote, ‘correct,’ end quote. Does this mean that China will continue to ignore the international community? What other sanctions on China can we expect?”

Assistant Secretary Destro: Well, let me take the second question first. We don’t really comment on sanctions. What we call on is for the PRC to respect – to respect all of its workers, to respect – to stop the brutal repression and repressive campaign against the Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang. The PRC still claims that these minorities, including Uyghur intellectuals and professionals, are enrolled in vocational training and has provided no evidence for its claim that 90 percent or more of the camp victims have graduated from this so-called training. So what I want to emphasize here is that the Chinese Government’s actions speak far louder than its words.

Ambassador Richmond, did you want to comment on that one?

Ambassador Richmond: Yeah. I think your point on sanctions is absolutely right. We can’t comment on those. But the first question really calls on a forecast, on a prediction of what the future conduct of the Chinese Communist Party will be. And we can only hope and encourage them to align with international human rights standards and make sure that there is no state-sanctioned forced labor or other human rights abuses in Xinjiang occurring.

Moderator: Thank you very much. And our next question goes to – comes from Asan Ali from the Qazaq Times in Kazakhstan, who asks: “What advice can the United States give to the Kazakhstan authorities who persecute ethnic Kazakhs who illegally cross the border with Kazakhstan for the sake of confidentiality?”

Assistant Secretary Destro: Well, thank you for the question. The – Secretary Pompeo met with the foreign minister, Mukhtar Tleuberdi, on February 2nd and raised concerns about the more than 1 million Uyghur Muslims and ethnic Kazakhs that the Chinese Communist Party has detained in Xinjiang just across the border. We encourage Kazakhstan to reserve – to resolve the legal status of asylum seekers from Xinjiang and encourage Kazakhstan to allow NGOs advocating for such individuals to operate freely.

Ambassador Richmond: I would just add to that, to what Ambassador – or Assistant Secretary Destro shared, that we have asked in the United States TIP Report, in the 10 recommendations that we provided for Kazakhstan, to include a remedy other than deportation for individuals that are found to be victims – victims of forced labor. Obviously, Assistant Secretary Destro is thinking about a larger range of human rights abuses. But we would note that we’ve called upon the Kazakh Government to do more to fight human trafficking, particularly that of individuals who include ethnic Kazakhs who are the victims of trafficking.

And they can do it through a couple of ways. One is by amending their law, amending the Kazakh law, to include force, fraud, and coercion as an element of the crime and not just an aggravating circumstance. That’ll bring it into consistency with international law. Another thing that they could do is reverse the four-year decline in convictions for human trafficking. We’ve seen it fall all the way, over the last four years, to only eight convictions, which is a meager number given the scope of the problem in the country.

Assistant Secretary Destro: And if I could –

Moderator: Thank you very –

Assistant Secretary Destro: If I could just add one thing at the end, it’s also true that Central Asian countries should really stand up for these victims. I mean, they should join us so that this is not simply an attack on China. We’re simply pointing out what China’s doing. And I’ve been trying to work closely with as many Muslim countries in the Organization of the Islamic Conference to get everybody together and to recognize this moral travesty for what it is.

Moderator: Thank you very much. So we’ll move on to our next question, which comes from Nicholas Schifrin, Nick Schifrin from PBS NewsHour. And Nick asks: “We’ve seen two DHS seizures of products that have come into the U.S. thanks to specific WROs. Should there be a more regional WRO that applies to all products coming out of Xinjiang? And is there any progress on the technology that could determine whether cotton comes from Xinjiang? Thank you.”

Ambassador Richmond: Well, I’ll take this one first. We’re incredibly encouraged by the increased number of withhold release orders that have been issued by Customs and Border Protection as part of Department of Homeland Security. The whole point of these withhold release orders is basically to say, if there’s a good made with forced labor or prison labor, it’s not going to be able to be shipped in to disturb markets. That is, product that is made with forced laborers shouldn’t be competing against products that are made with free laborers, who have to be paid market wages.

So we’ve seen an increase, including several recent withhold release orders, focused on companies that are bringing things out of Xinjiang. There has been a vigorous discussion about the application of a regional withhold release order and the pros and cons of that. We obviously want to consider the merits of that. But what we want to do as the United States is send a clear message that products that are made with forced labor are not going to be allowed to come into the United States.

To that end, we’ve issued a business advisory to encourage companies to consider due diligence and to try to determine what, if anything, they can determine regarding forced labor in the – in the companies that they are sourcing product, produce, or parts from.

Assistant Secretary Destro: And if I can address the parts of the question about the technology, there is really interesting technology out there that would allow you to find out where certain minerals and materials are sourced. But I think the easiest and perhaps the most fruitful way to go about doing this is to reach out to the companies that are doing the importing and to encourage them to really get down into the depth of their supply chain and to find out what’s actually going on. My experience in speaking with companies – and we’re scheduling meetings with companies as we speak – my experience is that most companies want to do the right thing. They just don’t know how to get down far enough into that supply chain.

And when you actually look at the – what the supply chains look like, it’s bewilderingly complex, especially when you deal with something like cotton, which goes back and forth across borders several times as they’re spinning it, taking it from cotton, and ginning it, and spinning it into yarn, and you know. So it’s a pretty complicated issue. But boy, it’s a fascinating one, and we haven’t yet really even begun to encourage consumers to make these kinds of demands on the companies who are selling them goods.

Moderator: Thank you very much. And to continue with the topic of forced labor, Kulpash Kanyrova from InBusiness Kazakhstan asks: “Muslim cheap labor is profitable for business. Which U.S. companies have refused to cooperate with China? And is there any official data as to how many Muslims are in labor camps in China today?”

Assistant Secretary Destro: Well, the numbers that we’ve seen, there’s more than a million ethnic Uyghurs and Kazakhs and other ethnic and religious minorities have been detained since April 2017. We’re getting more and more reports about this happening to Tibetan Buddhists as well.

And the question, “Which companies have refused,” if I get – if I have that question right, that’s not an easy question to answer. What I would like an answer to – and if you can get it, we’d all appreciate what the answer is – is why have the members of the Organization of the Islamic Conference not come to the – to the defense of their fellow religionists? We’re more than happy to work with them, and I stand ready to travel anywhere that needs to happen to get people organized.

Moderator: Thank you very much. So our next question comes from Ken Cheng from Epoch Times in Taiwan. And the question is: “Secretary of State Pompeo and Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Brownback publicly expressed concern for the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners by CCP, which has lasted for 21 years. One of the cruelties done by the CCP is forced organ harvesting. Would the Department of State step in and take specific actions to stop the forced organ harvesting by the Chinese Communist Party?”

Assistant Secretary Destro: Well, I can’t think of a more horrific human rights abuse than stealing somebody’s liver. I mean, this is – this is – we have had consistent reports of this. We have actually looked into allegations of it. And I encourage anybody who has information that we could use to nail this down to please be in touch with us.

Ambassador Richmond: I’ll also say that the removal of organs is one of the forms of exploitation under the Palermo Protocol, the UN protocol against trafficking in persons. And we continue to gather information about this, and like Assistant Secretary Destro, would call upon folks to provide information to the international community so that this issue can be raised with specifics and examples and any data that is available on the multilateral stage.

Moderator: Wonderful. Thank you very much. I believe we have time for one last question, and this question goes to Amy Chew from the South China Morning Post. And Amy asks: “Last month, Malaysia said it would not entertain a request to extradite ethnic Uyghur refugees to China, and will allow them safe passage to a third country should they feel their safety is at risk. How do you view this? Would it encourage other Muslim-majority countries to do the same at a time when China is pouring huge investments into countries like Indonesia and Pakistan, to name a few?”

Assistant Secretary Destro: Well, we always encourage countries to respect their international obligations with respect to refugees and people seeking asylum. We applaud what the Malaysians have done; this is simply basic respect for human rights. I mean, people are not fleeing to become economic refugees; they’re fleeing for their lives and for their families. So we applaud what they do. We encourage other countries, not simply Muslim countries but all countries, to recognize that this is a big problem and that these refugees have very serious problems and they should not be sent back.

Ambassador Richmond: And I think this is a larger pattern of doing the right thing. We want to make sure that not only are the Uyghurs not sent back to their trafficker, the Chinese Communist Party in China, we want to make sure that no victims of human trafficking are sent back to their traffickers, regardless of what country that might be. And so we want to make sure that there are alternatives to deportation, ways for refugees or human trafficking victims to find some sort of immigration status that allows them to remain and recover from the trauma that they’ve endured.

Moderator: Thank you very much. And unfortunately, that is all the time we have today for questions. I would like to turn it back over to Assistant Secretary Destro and Ambassador Richmond for any final comments or remarks.

Assistant Secretary Destro: Well, thank you very much. I’m only going to say a couple of words here. I want to thank you today for participating in the press conference. We take freedom of the press very seriously here, and we really welcome your inquiries.

I think what we need to remember here, and this is the closing thought I’m going to leave you with, is that modern slavery still exists. And every single one of us, every person of good faith no matter what religion, no matter what country, no matter what region, no matter what ethnicity, has an obligation to put a stop to it.

Ambassador Richmond: Well said. Well said. I’ll just join Assistant Secretary Destro in expressing my gratitude for everyone who’s joined this call today. Grateful for the role of the press in holding governments and culture to account. And I’d also say that not only is there a great degree of urgency around the issue of human trafficking, when we think about just the sheer numbers that have been estimated of almost 25 million individuals who are currently victims; there is a sense of urgency around it that we need to do something right away.

But there’s also a sense of doability. These are – these are issues we could tackle. These are issues that governments around the world are capable of addressing by just following the “three P paradigm”: that is, the P of prosecution – holding traffickers to account, governments or individuals; or the P of protection – how do we protect victims who have experienced this trauma; and then third, the P of prevention – how do we tackle the systems that make it easier for traffickers to operate. And as we do that, I think we’ll see great success in this issue.

Moderator: Wonderful. Thank you very much. Thank you, Assistant Secretary Destro, and thank you, Ambassador Richmond, for your time today, for joining us. And thank you to all the journalists for your questions.

We will send links shortly to all of our participating journalists to the recording of this briefing and provide a transcript as soon as it is available. We’d also love to hear your feedback, and you can contact us at any time at [email protected]. Thanks again for your participation, and we hope you can join us for another press briefing soon. This ends today’s briefing.

# # # #