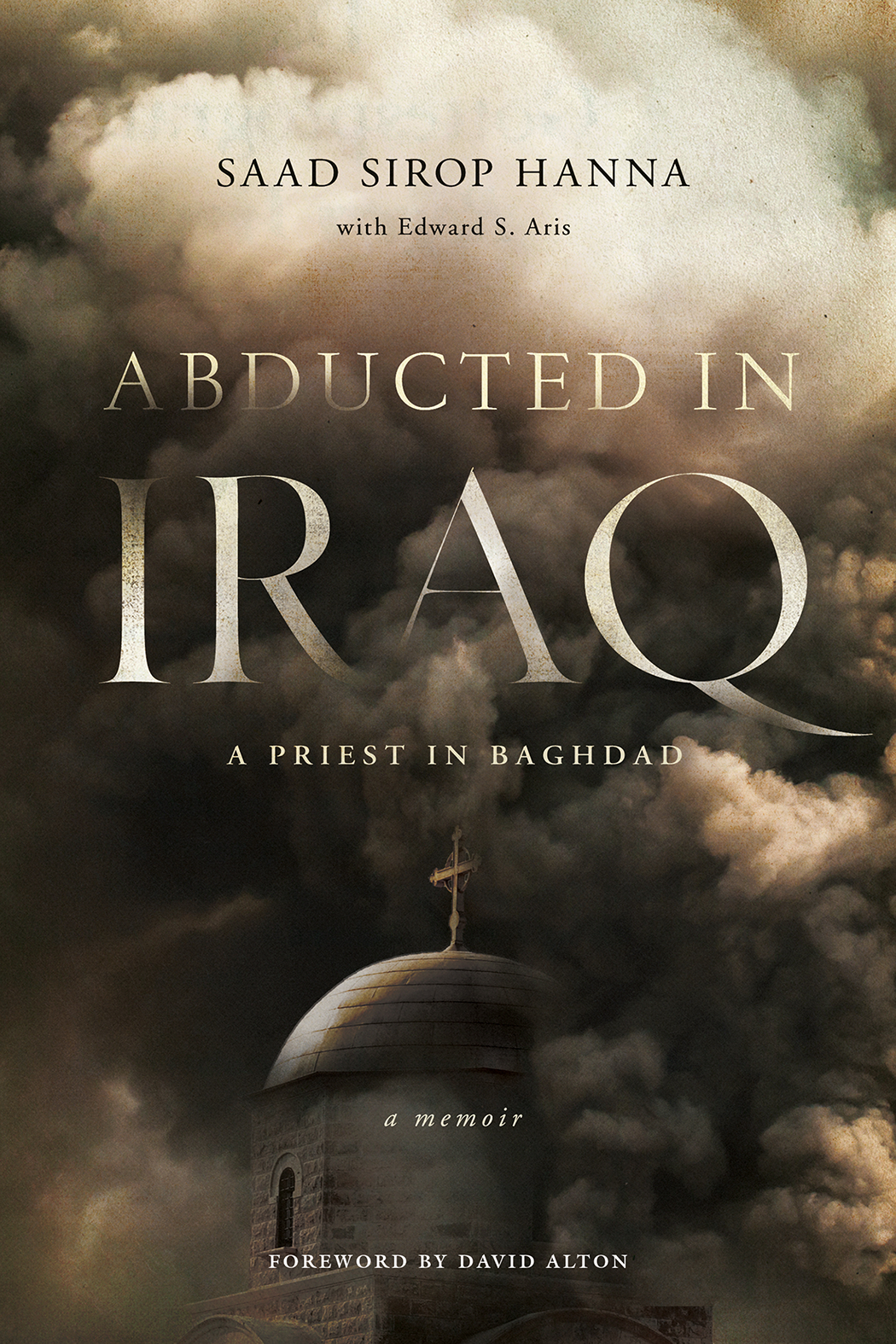

Abducted in Iraq

A Priest in Baghdad

Saad Sirop Hanna, with Edward S. Aris

Foreword by David Alton

How do we respond in the face of evil, especially to those who inflict grave evil upon us? Abducted in Iraq is Bishop Saad Sirop Hanna’s firsthand account of his abduction in 2006 by a militant group associated with al-Qaeda. As a young parish priest and visiting lecturer on philosophy at Babel College near Baghdad, Fr. Hanna was kidnapped after celebrating Mass on August 15 and released on September 11. Hanna’s plight attracted international attention after Pope Benedict XVI requested prayers for the safe return of the young priest.

The book charts Hanna’s twenty-eight days in captivity as he struggles through threats, torture, and the unknown to piece together what little information he has in a bid for survival. Throughout this time, he questions what a post-Saddam Hussein Iraq means for the future, as well as the events that lead the country on that path. Through extreme hardship, the young priest gains a greater knowledge both of his faith and of remaining true to himself.

This riveting narrative reflects the experience of persecuted Christians all over the world today, especially the plight of Iraqi Christians who continue to live and hold their faith against tremendous odds, and it sheds light on the complex political and spiritual situation that Catholics face in predominantly non-Christian nations. More than just a personal story, Abducted in Iraq is also Hanna’s portrayal of what has happened to the ancient churches of one of the oldest Christian communities and how the West’s reaction and inaction have affected Iraqi Christians. More than just a story of one man, it is also the story of a suffering and persecuted people. As such, this book will be of great interest to those wanting to learn more about the violence in the Middle East and the threats facing Christians there, as well as all those seeking to strengthen their own faith.

” Abducted in Iraq is Saad Hanna’s riveting account of his captivity in Iraq among Muslim extremists. The story Hanna tells will leave readers breathless. He recounts how his captors seized him from his car in Baghdad, tortured him, and repeatedly demanded that he convert to Islam. Through it all Hanna held courageously to his Christian faith, and refused stubbornly to hate his captors. By the end of Abducted in Iraq readers will not only be inspired, they will also gain a new sense of compassion for those who suffer from religious violence.” — Gabriel Said Reynolds, author of The Emergence of Islam: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective

“Bishop Hanna’s testimony and story deserves to be read by anyone who has ever wondered how they would react if they were kidnapped, tortured, told to abjure their faith, and faced likely death. It should be read by anyone with even a passing interest in the violence and hatred that has disfigured Iraq and that now disfigures Syria. It should be read by anyone interested in the widely dishonoured Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—born in the ashes of Auschwitz, and which asserts our right to freedom of religion or belief. And it should be read by anyone who feels they need to be better informed about the ancient churches of the Middle East and the existential threat that these Christians face.” — David Alton, professor emeritus, John Moore’s University, Independent Life Peer of the British House of Lords

“It is a fact of journalism that distant tragedies are not taken seriously unless a face, a personal experience, makes it real. This is such a personal story, and told perhaps better than any trained journalist might.” — Carl Anderson, Supreme Knight, Knights of Columbus

ISBN: 978-0-268-10293-7

184 pages

Publication Year: 2017

Book Review

Saad Hanna, Light in Darkness

David Alton

In the summer of 2016 the University of Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters Medieval Institute published details of visiting scholars using the Institute’s celebrated libraries for their research. Among those listed is an Iraqi bishop who is preparing a translation from Syriac to English of the writings of the Chaldean Patriarch, Timothy I, who lived from 728-823.

Although more than one thousand years separate them, Bishop Saad Sirop Hanna – like Patriarch Timothy is also a Chaldean. Born in Baghdad in 1972 he was ordained to the priesthood in 2001. Titular bishop of Hirta sinec 2014 he has served as the auxiliary bishop of Babylon – a title which, along with remote Christian villages on Iraq’s Plain of Nineveh, remind us that even before Patriarch Timothy Mesopotamia had important biblical associations. Christians have lived in this part of the world for close on 2000 years and many speak the Aramaic language of Jesus.

Bishop Hanna holds a doctorate in philosophy, a degree in aeronautical engineering, speaks four languages and has published several learned articles. In his future work he will doubtless take us back to Patriarch Timothy’s eighth century record of the inconclusive debates on the rival claims of Christianity and Islam which reputedly took place in 782. Translated in 1928 into English by Alphonse Mingana – who gave it the title “Timothy’s Apology for Christianity” – the text is respectful towards Islam and was presumably written in the hope of encouraging greater mutual understanding – a theme which is close to Bishop Hanna’s own heart.

However, Bishop Hanna’s self-evident scholarship and learning is not the reason to ensure that his Light in Darkness is among your prized possessions. This beautiful book is the captivating story of a faithful Iraqi priest who was abducted and tortured and who resolutely refused to betray his beliefs or to hate his captors.

Light in Darkness opens with the arresting and undisguised terror of a young priest’s abduction on the feast of the Assumption, August 15th, 2006. Fr.Hanna had said Mass for his parishioners and, on leaving his Baghdad church, was seized by a group of Jihadists linked to Al-Qaeda.

Blindfolded, handcuffed, bundled into the boot of a car, he says that he felt “like a man clinging to a torch as he plummets through darkness.”

For the ensuing twenty seven days he was held as a hostage, tortured, and beaten, becoming a bargaining chip and the subject of ransom demands. His captors tortured him physically and tantalised him psychologically – offering freedom and the chance to become a respected teacher in their new Islamic Iraq if only he apostatised and renounced his Christian faith. At one point his captors made contact with the U.S.Army but Fr.Hanna shockingly reveals: “The American Army knew where I was and chose not to save me.”

The first priest in Baghdad to have been abducted, Fr.Hanna says that his terrifying experience “taught me a lot about myself and about the relationship between the religions.”

This is Father Hanna’s personal story – autobiographical but woven within it are important insights into what has happened to the ancient churches of this benighted region and how we in the West, having accelerated the assault on Iraq’s Christian community, have done precious little since then to protect them or to champion their cause

Bishop Hanna’s instructive story is the story of one man but it is also the story of a suffering and persecuted people.

We are reminded that Christianity has been present in Iraq since the first century; that it played a significant part of Iraq’s collective and communal life; and that Muslims and Christians have often lived alongside one another – without the visceral hatred which has come to characterise the Wahhabi strain of Sunni Islam; and that Saddam Hussein’s barbaric cruelties have been replaced by a different kind of cruelty – in which the Christian minority has been terrorised and hunted down – in what can only be described as genocide.

Bishop Hanna’s sobering account should challenge us, his readers, who live in the relative comfort and safety of the West, to re-evaluate our dismal record in relation to the beleaguered Christians of the Middle East.

The chilling statistics tell their own story.

Before the Iraq War, in 2003, around one and a half million Christians lived in Iraq: about 6% of the population. With the failure to create a stable and plural Iraq, Christians and other minorities have been caught in a no-man’s land – caught between a rock and a hard place. As they have either been killed, forced to convert, or fled, some recent estimates have put the number of remaining Christians as low as 200,000.

Bishop Hanna’s Chaldean Catholic Church – Eastern Rite and in full communion with Rome – is the largest Christian denomination.

The haemorrhaging of the Christian population has been accompanied by appalling acts of violence – raising again the question of how those responsible can reasonably claim to be adherents of what many insist is a religion of peace.

Fr.Hanna’s captors repeatedly told him – as they beat him or assaulted him with the butt of a gun “you will be a Muslim” – to which he replied la ikraha fid deen – the Islamic scripture which holds that no one can be forced or obliged to become a Muslim; that there is no compulsion in religion.

Yet, as his captors beat this blindfolded priest, they insisted on calling him a kafir – an infidel or unbeliever – warning him that if he failed to capitulate he would forfeit his life.

That these are not rhetorical flourishes is illustrated in the bloody beheading and mutilation of the Ortrhodox priest, Fr.Boulos Iskander, murdered in the same year as Fr.Hanna’s abduction; by the death in 2008 in Mosul of Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho, who died after being abducted; and by the deaths of Chaldean priests, deacons and lay people.

Recall that in 2007 Fr.Gassan Isam Bidawed Ganni was driving in Mosul with his three deacons. They were shot when they refused to convert to Islam. In 2010 an attack on an Assyrian Catholic church in Baghdad left 58 people, including 41 hostages and priests left dead.

Incidents like these subsequently became systematic when, in 2014, with the establishment of the caliphate, the Islamic State, there followed an orgy of violence – including beheadings accompanied by the burning of churches and the confiscation of properties.

ISIS issued a decree that Christians must pay a special tax or else convert or die. Christian homes in Mosul were painted with the Arabic letter for Nazarene and their homes and businesses were appropriated by the Islamic State.

In summer of 2016, in its magazine Dabiq, ISIS now describes Christians as “pagans” thus freeing ISIS of any pretence that these are “people of the book” and may, like Iraq’s Yazidis, be killed or enslaved.

The British Jewish intellectual, Maurice Glassman, has described the Christians of the region as “the new Jews” and, tellingly, asks why Christians are not more vocal about the treatment of their co-religionists.

Although the US Congress, the British House of Commons and the European Parliament have all declared that what is underway is a genocide, where is the International Criminal Court or a regional tribunal to bring to justice those responsible? Where are the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, who have utterly failed in their duty to uphold international law or to protect the most vulnerable? And where were we when Fr.Hanna was kidnaped by Jihadists?

The Patriarch of the Chaldean Church, Louis Sako, says that this war of attrition means that for the first time in Iraq’s history there are now no Christians left in Mosul – Iraq’s second largest city.

In “flashback” passages in Light in Darkness Bishop Hanna tells us that this cataclysm had its genesis in 2001 in New York in the murderous events of 9:11 which took the lives of 2,996 people and injured over 6,000 others.

On that dreadful day the young Saad Hanna was in Italy, a seminarian studying for the priesthood.

As he watched the unfolding horror of the twin towers he remarked to his fellow seminarians “the world is being turned upside down. America will not let this be.”

However, although he believed there would be an inevitable retaliation against the Arab world he did not believe it would be targeted and directed at secular Baathist Iraq – where Saddam was hated by the very Jihadists who had plotted and carried out the attack on the U.S.

When, in March 2003, the invasion of Iraq occurred, the jihadist propaganda machine went into top gear caricaturing Coalition forces as infidels embarked on a holy war against Islam. Iraq’s indigenous Christian population was caricatured as a fifth column, sharing the same religion as the invaders. Simultaneously, along with being painted as the enemy within, Christians were caught in the cross-fire of the war which continues to rage between Sunnis and Shiite Muslims.

Saad Hanna believes the Iraq war was waged as “a war without precision” and that the failure to plan for its aftermath has had devastating consequences – not least for the country’s minorities and as a consequence of the role reversals of formerly dominant Sunnis and oppressed Shias.

Bishop Hanna correctly believes that without an end to this violence and without a determined campaign to replace bloodshed with healing and reconciliation it will be impossible to create a strong or stable civil society.

The reader is left in no doubt that Bishop Hanna loves his country and believes that the absence of Christians will be bad for the Muslim population as well as a tragedy for the dispossessed.

For the future, Bishop Hanna is clear that Christians in Iraq should favour a united Iraq, and concentrate on promoting the idea of citizenship, not on enclaves based on an ethnic or religious tradition; that Christians must adopt a language promoting unity; that they must work for a true and lasting reconciliation; that Christians in Iraq must be united and work together with all of the country’s political parties excluding no one person or group for ethnic or sectarian reasons (Chaldeans, Assyrians, Syrians, Armenians, and Arabs); and that they must build a Christian politics that is faithful to Gospel principles and the Church’s teachings.

He argues that Iraq’s Christians have always lived in peace within the greater community and, over many centuries, have actively participated in the building of the nation – and must do so again.

That Bishop Hanna is going nowhere and is in this for the long term was clear from the moment of his ordination when the young Fr.Hanna chose to return to Iraq, telling the charity Aid to the Church In Need:“I love Iraq and I love my people, so I wanted to continue working here as a priest.” He also believes that he has an appointed task to ensure that the West has a deeper understanding of the history of Christians in Iraq: “they do not know who we are, how we live here, what we do here…. It is so important to exchange ideas in order to understand how faith has been implemented in different societies.”

Happily, it was his very love and commitment to his people and his country that probably saved his own life.

We learn in Light in Darkness that his captors accused him of being an American agent with links to Washington.

Fr.Hanna told them that he didn’t know any Americans and asked his captors to go and ask the Christian and Muslim families of his Baghdad parish whether the charge was true or false. They did and, although it did not stop them beating and intimidating him, they conceded that his account was correct.

That they took the trouble to verify what he had said is unexpected.

There are other incident like this which confound some of our usual assumptions and stereotypes.

The conversations he had with one of his guards, Abu Hamid, and that guard’s small acts of kindness, are a timely reminder that, even in the heart of darkness, the small light of human kindness can burn.

When Fr.Hanna was finally released – dumped miles from anywhere and told to walk to the highway (where he finally rendezvoused with his brother) – one of his captors quizzed him directly: “You don’t hate us, do you?” He responded: “No I don’t hate any person. My faith asks this of me – to love all people, even those who harm me.”

And, ultimately this book is a love letter.

He says of love: “Love. I used the word often and yet it is one of the few for which there is no substitute. At its essence Christianity is love, and love is not surrender. It is not to meekly endure, nor is to blindly turn away from those in grave need of assistance….These are delicate times with no simple easy solutions. Love must be the driving force for all people, to ‘love your enemy’, to look beyond the threats of the here and now, to look beyond ethnicity, creed, culture or religion, and to connect on a level of shared humanity.”

“We see fear and hatred close at hand and are tempted to paint love

as weakness. Christ is love and love was never meant to be easy. It is the hardest thing of all and yet it will always be the only answer.”

Bishop Hanna says that his experiences at the hands of his captors was like being reborn and set on fire with new zeal for this Gospel of life and love: “I am reborn again: with a mandate to tell others that faith need not diminish in the face of difficulties but that it can blossom to a greater vision, where a belief in the love of God compels us to see the love in one another.”

This greater vision and a belief in the enduring power of love to defeat hate is at the heart of Light in Darkness.

Bishop Hanna’s testimony and story deserves to be read by anyone who has ever wondered how they would react if they were kidnapped, tortured – told to abjure their faith – and faced likely death; it should be read by anyone with even a passing interest in the violence and hatred which has disfigured Iraq and which now disfigures Syria; it should be read by anyone interested in the widely dishonoured Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – born in the ashes of Auschwitz and which asserts our right to freedom of religion or belief; and it should be read by anyone who feels they need to be better informed about the ancient churches of the Middle East and the existential threat which these Christians face.

David Alton is former Professor of Citizenship at Liverpool John Moores University and serves on the Board of the charity Aid to the Church In Need. He has been a member of the British Parliament since 1979, as a member of the House of Lords since 1997. www.davidalton.net