The Four Quartets will be read by Jeremy Irons on BBC Radio Four on Saturday January 18th, 2014, at 14:30 – 15.45 pm with an introduction by Michael Symmons Roberts, Lord David Alton and Gail McDonald.https://myshare.box.com/s/jbtssur3j8qebn9oqcfe

http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/proginfo/2014/03/r4-saturday-drama.html

Saturday Drama: Four QuartetsJeremy Irons reads Four Quartets by TS Eliot.

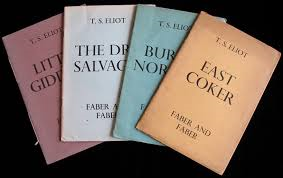

Four Quartets is the crowning achievement of TS Eliot’s career as a poet. While containing some of the most musical and unforgettable passages in 20th century poetry, its four parts – ‘Burnt Norton’, ‘East Coker’, ‘The Dry Salvages’ and ‘Little Gidding’ – present a rigorous meditation on the spiritual, philosophical and personal themes which preoccupied the author.

It was the way in which a private voice was heard to speak for the concerns of an entire generation in the midst of war and doubt that confirmed it as an enduring masterpiece.

Producer/ Susan Roberts for the BBC

T.S.Eliot: The Four Quartets

1. Where does it sit in the canon of English Literature?

In thinking about Eliot’s masterpiece I found Dr,.Paul Murray’s “T.S.Eliot and Mysticism: The Secret History of “Four Quartets” indispensable.

It’s over forty years since, as a school boy, I discovered Eliot, and it’s nearly 80 years since he began writing Burnt Norton, the first of his Four Quartets. Perhaps the first thing to say is that the mere passage of time has not dulled the poems, having lost none of their status as strikingly ‘modern’ poetry.

I read the Quartets after I had read The Waste Land – Eliot’s very bleak view of a maimed and disfigured England – and they invite the reader to consider how the waste lands of our lives might be transformed.

They are devotional and meditative poems but just as John Donne and the devotional poets of the seventeenth century, replaced the language of the Elizabethan era, Eliot writes in a new and original way – displaying religious genius, amazing originality, and extraordinary learning and depth. His originality is central to this masterpiece.

Eliot, of course, draws on innumerable sources – theological, philosophical, mystical, mythical, and poetic – so much so that at times he has been accused of a sort of literary kleptomania. He countered this by saying that “true originality is merely development.”

More than any other source, I think we need to see The Quartets in parallel to Dante.

Ezra Pound said of Eliot “His was the true Dantean voice” while Eliot himself once remarked:”I regard his poetry as the most persistent and deepest influence on my own work.”

Dante’s imagery: the idea of the “refining fire” in the Four Quartets comes fromPurgatorio and the celestial rose and fire imagery of Paradiso are all incorporated into the poems. Those we meet in the Quartets, trapped in time, are like those stranded between life and death in Dante’sInferno.

Eliot’s own assessment of where he sits within the canon of English literature is revealing. He said: “My reputation in London is built upon one small volume of verse, and is kept up by printing two or three more poems in a year. The only thing that matters is that these should be perfect in their kind, so that each should be an event.” That’s a pretty good yardstick against which to measure the blissful perfection of the Quartets.

He had an aversion to the emotionalism of the romantics and his poetry sparked a revival of interest in the metaphysical poets – infusing his own work with challenging psychological, sensual, and unique ideas.

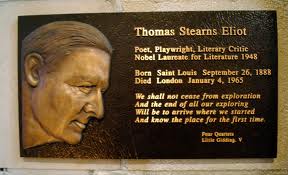

Eliot, himself, regarded Four Quartets as his masterpiece, and it was the work which led to his being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The vast number of learned articles and books of literary criticism about Eliot and his poetry underline the claim of genius.

2. The Historical Context?

Written just before and during the Second World War, the first poem, Burnt Norton was published in 1936, East Coker in 1940, The Dry Salvages in 1941, and Little Gidding in 1942.

Burnt Norton is named after a Manor House and he wrote it while working on his play, Murder in the Cathedral. For me, it conjures up the lost opportunities of those inter war years“Down the passage which we did not take, towards the door we never opened, Into the rose garden.”

But this is deeper than simply mourning what might have been. In the preceding years we had lost our innocence; we had lost a blissful world just as mankind had lost humanity’s primeval home through our folly in the Garden.

The second Quartet, East Coker, was published just after the War began. Eliot passionately believed that Germany and Nazism had to be fought and defeated, and England, with its ancient lineage, vigorously defended.

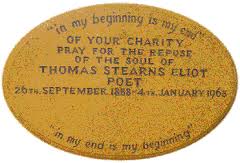

He had visited East Coker, a small village in Somerset, two years earlier. It was where his own ancestors had lived. Some emigrated to America in the 17th century – and the poem has a flavour of the pilgrim father. East Coker is where Eliot asked for his own ashes to be buried. And the poem examines the cycles of life and death: “In my beginning is my end.”

It is the poem which inspires me the most – especially the link which Eliot makes between human suffering and the Good Friday cross; the poet’s own admission of his own helplessness; the procession of statesmen, rulers, merchant bankers and the rest who “all go into the dark” and the appearance of the wounded surgeon and the deep compassion of the healer’s art, needed by Eliot’s and every other generation.

Dry Salvages came a year later and was written during air raids on London. Eliot himself had volunteered as a night watchman to help during the air raids. The London Blitz had begun on September 7th, 1940 and Hitler’s intention was to demoralise the population. 348 German bombers and 617 fighters began a blitzkrieg that continued until the following May. Underground stations sheltered as many as 177,000 people each night – and in one incident alone 450 people were killed.

This was the backdrop to a poem which warns us that if we allow ourselves to simply drift like flotsam and jetsam we will be wrecked on the rocks – the dry salvages – which are a group of rocks of Cape Ann, in Massachusetts. More than anything else Eliot now tells us to pray.

A year earlier, in 1939, King George VI, in his Christmas broadcast quoted Minnie Haskins, “And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year, Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown, And he replied: Go out into the darkness and put your hand into the hand of God.”

In May 1940 King George then called the whole nation to prayer and to commit their cause to God, as 335,000 men were waiting to be evacuated from Dunkirk. Mirroring the King’s words, Eliot calls us to “prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action” invoking the “Lady, whose shrine stands on the promontory”

and writing:

“Repeat a prayer also on behalf of women who have seen their sons or husbands setting forth, and not returning” and “ Also pray for those who were in ships, and Endeed their voyage on the sand, in the sea’s lip.”

Little Gidding was completed in 1942, as Britain’s fortunes were turning. It was the year of El Alemain and came as America entered the war after the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbour.

Here Eliot is reminding us that the fire of bombs brings death but the fire of Pentecost brings life. He is saying that the enemy may be defeated and repeatedly uses the refrain of Julian of Norwich that “all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well” if only we realise that alienation from God is more dangerous than Hitler; that we must come through the fire of purgation to new life and resurrection.

![]()

3. How does it relate to Eliot’s Christianity?

Eliot was received into the Church in 1927. An Anglo-Catholic, he was part of a generation of talented Christian writers – CS Lewis, JRR Tolkien, Dorothy L Sayers, G.K.Chesterton, Walter de La Mare and Evelyn Waugh among them. But Eliot was a Christian writing in an era of scepticism and atheism.

Virginia Woolf needled Eliot about religion and once asked him “did he got to church?” “did he hand round the collection plate?” “Yes, O really!” “did he pray, and what did he experience?”

In answer, Eliot apparently leaned forward, bowing his head prayerfully, and described how he attempted concentrate, to forget himself, seeking union with God.

And that I suppose is the essence of Four Quartets: it is his attempt to make music – what he called “the music of ideas” – it is a spiritual canticle with a number of central themes and subjects but they are all bound together in Eliot’s mysticism.

He draws heavily on the mystics such as St.John of the Cross and Julian of Norwich and writings such as “The Cloud of Unknowing.” In 1930 he wrote that “forest sages, desert sages, men like John of the Cross and Ignatius really mean what they say because they have looked into the abyss.” Simultaneously he rejects occultism, spiritualism and contrasts magic with mysticism.

But he is also influenced by Kierkegaard, the 19th century Danish theologian and by his contemporary, Karl Barth – and he sides with them in their battle for a new Protestant orthodoxy against liberal Protestantism. From the Catholic tradition he had a love of Thomas Aquinas and had been influenced by Jacques Maritain, the Thomist theologian. And there are Buddhist and Brahmin influences – although he asserted that “Christian revelation is the only full revelation.”

While Eliot admits his knowledge of Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises it is the more precise Augustinian method of establishing self knowledge which attracts him. There’s a groping into the darkness and depths of the soul; a delving into sensory memories; a desire to risk unbearable experiences – a willingness to “disturb the dust”; the pointing “to one end which is always present,” the use of the elements, air, earth, water and fire, to define his own spiritual journey.

Eliot takes us into what time means to him; then into the unsatisfactory nature of the world; then to purgation; into lyrical and intercessory prayer. Through the Annunciation, Incarnation, Redemption and Resurrection, he helps us find the way to God.

Contrast Eliot with Gerard Manley Hopkins. Hopkins believed in the Doctrine of Immanence – and saw God in all things: In “As Kingfishers Catch Fire, Dragonflies Draw Flame” he wrote that“…Christ plays in ten thousand places, Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his To the Father through the features of men’s faces.” he said “Glory be to God for dappled things.” –

Eliot, by contrast, believed in the Doctrine of Transcendence – insisting on a separation of the human and divine, of the temporal and eternal – which takes you into the way of interior darkness, self denial, purification, self exploration, self criticism (as in The Spiritual Exercises) and self discovery. George Orwell called this “a melancholy faith” and, although there is sometimes a

Puritan distaste for life, for me Eliot represents man’s yearning to find purpose and meaning in life. At times his voice is that of an Old Testament prophet. In fact, East Coker opens with a text which is largely based on the second chapter of the Book of Ecclesiastes: “a time for every purpose under heaven”.

Eliot himself mediated n the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary – the agony of Jesus in the Garden; the scourging of Jesus at the pillar; the crowning with thorns; the carrying of the cross; and the crucifixion and death of Jesus.

Having journeyed through these events, the poet arrives at his destination: “and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

Asked whether the Foreign Secretary intends to take steps to ensure that China’s actions against Uyghurs is recognised as genocide through international courts and by working with international partners, in accordance with his remarks in March 2023, the FCDO trots out their usual evasive circular argument. In Opposition, today’s Ministers voted to change the law on Genocide Determination. They should now stand up to the officials who try to use determination of atrocities as a diplomatic tool rather than honouring the obligations in the Genocide Convention.

Asked whether the Foreign Secretary intends to...