William Roscoe’s Poetry: October 2015 Talk By David Alton

It has been a tradition at the Roscoe Lectures to conclude with a stanza drawn from one of Roscoe’s poems.

As we celebrate the bicentenary of his appointment as a Freeman of Liverpool we have collated this very brief anthology of extracts from some of those poems. We hope you will keep it as a memento of this evening’s celebration dinner.

That we have an extensive collection of Roscoe’s poetry is largely thanks to the work of Dr.George Chandler, the City’s, post-war, highly accomplished librarian who, in 1953, published a biography and collated an anthology. Chandler’s collection begins with “A Hymn to the Deity” and conclude with a short verse, “Champion of Freedom,” which Roscoe dedicated to one of his political heroes, Charles Fox.

This short collection begins with two poems that reflect on the value of education.

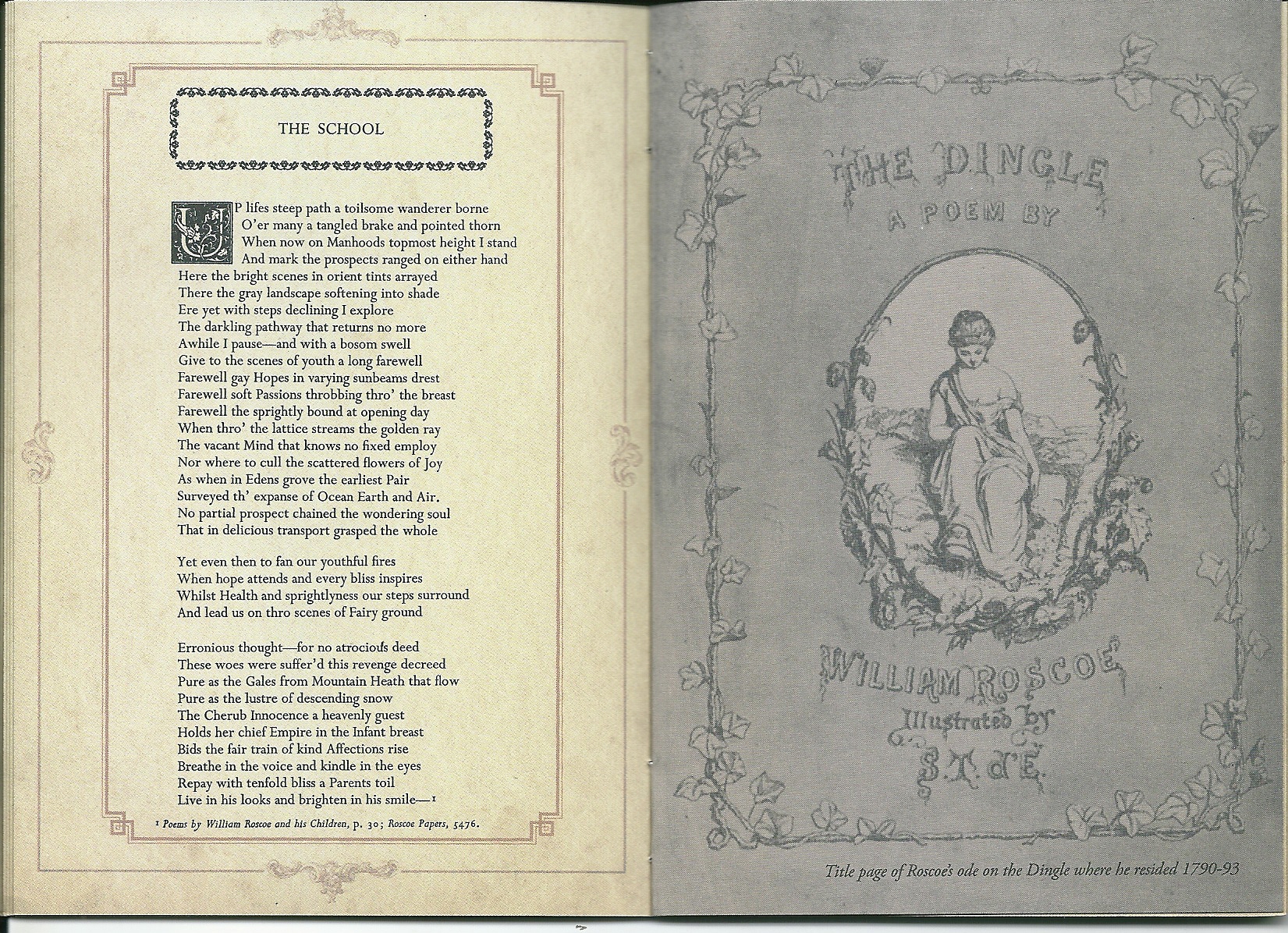

Roscoe reminds us of “the vacant mind that knows no fixed employ” while an educated mind becomes “deaf to the Bigots frantic voice, conducts each dubious step by Reason’s plan.” Despite his humble origins Roscoe became a “scholar gentleman” of the eighteenth century, passionate in his belief that “everything that is connected to the intellect is permanent”

He was one of the small Liverpool circle who insisted that education held the key to progress – both for boys and, way ahead of his time, for girls. One of that circle’s most notable achievements was the founding of an Institute for apprentice mechanics and engineers and which, over nearly two centuries, has evolved into today’s thriving Liverpool John Moores University.

Demonstrating how the ladder of learning leads to personal advancement, and to the enhancement of civic life, this self-taught man would become the father of Liverpool culture, modelling himself on one of his other heroes, Lorenzo de Medici – the great Renaissance statesman and a doyen of the arts -patron of scholars, artists, and poets.

Roscoe’s interest in design finds an echo, in 1774, in his first published poem, with the rather cumbersome title: “Ode on the Institution of a Society in Liverpool for the Encouragement of Designing, Drawing, Painting, etc.”

This interest in design led Roscoe to learn Latin, French and Italian in order to understand better the ideas and works of Leonardo de Vinci.

Excitingly, through these studies, Roscoe discovered one of that polymath’s lost treatises on mechanics.

Inspired by his mother’s love of poetry, Roscoe tackles many themes in his own verse but, most notably, his poems dedicated to freedom and opposing tyranny led to the awakening of social conscience in Liverpool.

One of the earliest poems, “Mount Pleasant”, written when he was just nineteen and modelled on John Dyer’s “Grongar Hill”, is named for the place where William was born in 1753 and where many of his university’s buildings are located today. Roscoe’s father had a market garden in Mount Pleasant and, in 1831, his son would be buried there, next to the Unitarian Chapel where he had worshipped all his life.

The young Roscoe directs much of this poem at those who had grown wealthy through commerce – and the exploitation of African slaves – reminding them that earthly treasures – including the very city itself – will quickly disappear and that wealth and privilege should always be placed at the service of others. His admonishes his readers and warns “the time may come (O distant be the year) when desolation spreads her empire here, when trade’s uncertain triumph shall be o’er.”

This warning, that we will face the consequences of our actions, is nowhere more eloquently or powerfully recorded than in his long polemical poem “The Wrongs of Africa”.

Here, like an Old Testament prophet, he warns “Forget not, Britain, higher still than thee, sits the great Judge of Nations, who can weigh the wrong, and who can repay.” Its publication caused a ferment among the angry merchants of Liverpool who, in 1807, generated an estimated £17 million through the slave trade; a staggering sum by today’s standards.

Roscoe’s poetry encapsulates his strong political, religious and moral views, refusing to be intimidated by those who resented the many unpopular causes which he embraced – championing freedom and equality for Dissenters and Catholics, demanding political reform and the extension of the franchise, advocating peace and toleration and virulently opposing the hateful slave trade.

He gave the proceeds of “The Wrongs of Africa” to help found the London Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Other Liverpool subscribers included his friend, the Quaker, William Rathbone, and Roscoe’s brother-in-law, Daniel Daulby.

As one of the country’s leading abolitionists Roscoe was able, during his three month tenure as a Liverpool Member of Parliament, to vote with William Wilberforce against the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, telling the House “It is now upwards of thirty years since I first raised my voice in public against the traffic, which it is the object of the present Bill to abolish.”

For all this he paid a price – famously being assailed in the street where we meet tonight, Castle Street, as a mob of sailors, and others mired in the slave trade, beat him to the ground. This attack simply led to him redoubling his efforts refusing always to be ground down by defeat or intimidation.

Roscoe – a natural Whig –captures this reliance, and his passion for politics, in the poem “Song on the Liverpool Election of 1812” – which entreats the civic leader not to despair, to find fresh vigour, to “wage the bold war with corruption again” and to claim” the wreath wove by Liberty, Friendship and Love.”

Even as he approached the end of his life Roscoe continued to speak up for the voiceless.

Among those he cared for most were the destitute and the oppressed. In the last three years of his life we find him busy founding a Liverpool Association for Superseding the Use of Children in Chimney Sweeping – a cause which Lord Shaftesbury would bring to fruition.

But Roscoe was much more than a campaigner.

He was scientific in his observation of nature; a botanist and environmentalist; a poet, writer and educationalist; one of the greatest bibliophiles and collectors; a lawyer and a banker; a patron of high culture and the arts; and a philanthropist. And above all he was a deeply committed husband and father.

On February 22nd, 1781, he married Jane Griffies. His love poems to Jane, written during their four years of engagement, were published much later. But, equally touching, is “Some Forty Years”, written to celebrate their forty years of marriage – a time “of constant love and kind affection” while in his “Sonnet to Mrs.Roscoe” he reflects that “thy days with cloudless suns decline” while their marriage had been abundantly blessed by children who from “thy willing breast…those healthful springs…six sons successive, and thy later care, two daughters fair, have drank”.

While living at Allerton Hall – which he bought in 1799 – it was to his children that he wrote some of his most loved and popular poetry.

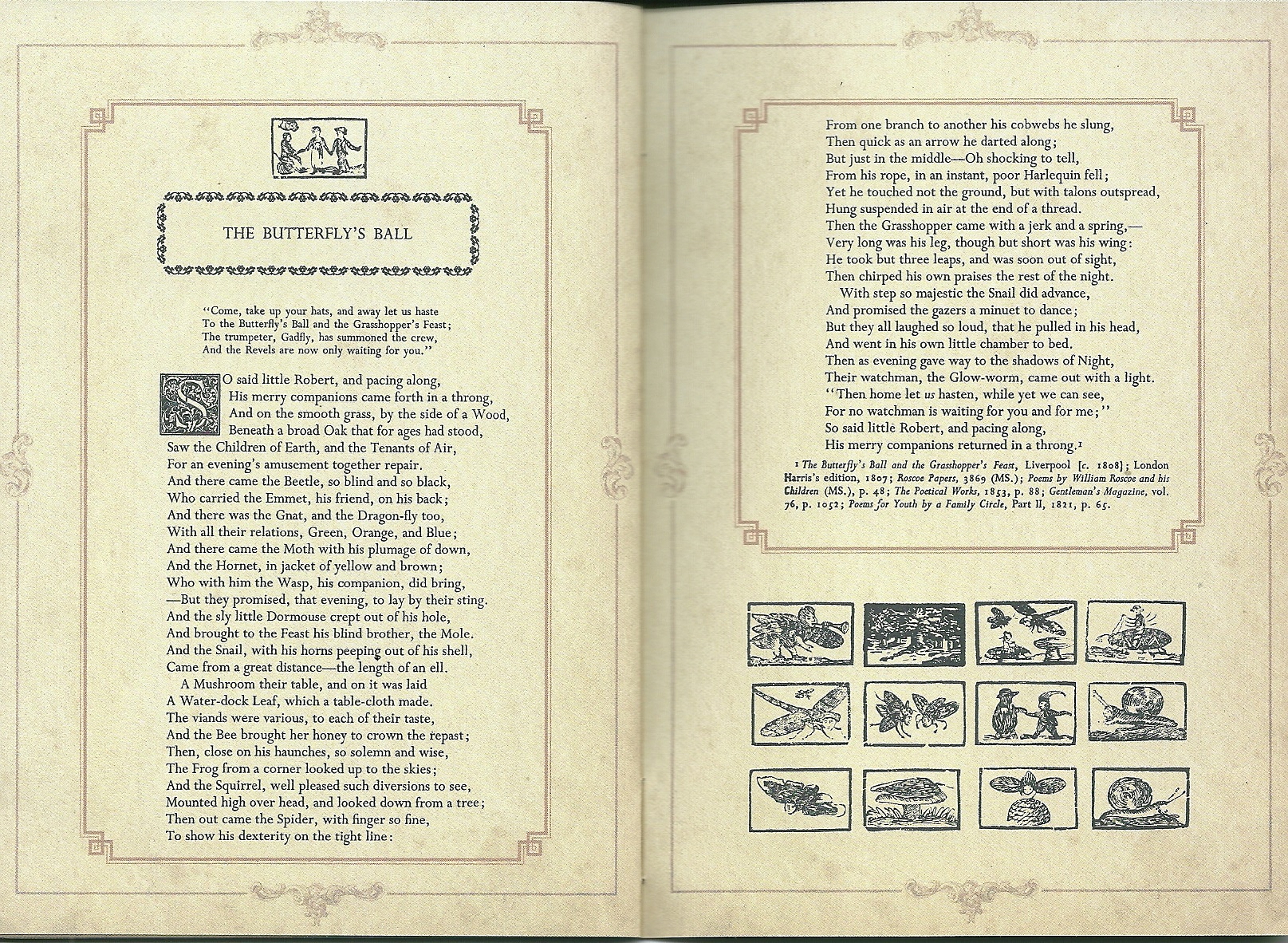

“The Butterfly ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast” was written for his young son, Robert, and was published in 1807. It quickly became a nursery classic – with King George III asking the composer, Sir George Smart, to set it to music for his daughters, the three princesses, Elizabeth, Augusta and Mary.

It was followed by “The Butterfly’s Birthday” and “The Spider and The Bee – A True Story”, which opens with the captivating and enthrallingly descriptive words: “With vicious thread and finger fine, the spider spun his filmy line…”

The Butterfly ‘s Ball concludes by reminding the children that even festivities have their end: “Their watchman, the glow-worm, came out with a light, “Then home let us hasten, while yet we can see, for no watchman is waiting for you and for me”; so said little Robert, and pacing along, his merry companions returned in a throng.”

Roscoe, himself, bore vicissitudes and hardship, and the disappointments and the cruelties of life – including his bankruptcy – with stoicism and fortitude.

He hoped that some little work of his might be remembered and that he had been able to leave behind something of worth. Of his impending death he wrote that “I wait the death-stroke from Thy hand And stoop resign’d to meet the wound….when removed from grief and pain, this fragile form on earth shall lie, some happier effort may remain, to touch one human heart with joy…Smite Lord! This frame shall own Thy power, and every trembling chord reply; Smite Lord! And in my latest hour, This failing frame shall ring with joy!” while in his poem “The Farewell” he asks that when we are separated “from the friends that we love when we wander alone…some soft recollections will still be in store.”

In 1931 Liverpool celebrated the centenary of Roscoe’s death and, in 1953, the city recalled the bicentenary of his birth. That we gather again, some two hundred years since his contemporaries conferred on him the dignity of being made a Freeman of Liverpool, to once again recollect his remarkable deeds and his notable achievements, suggests that his simple hope and modest wish has been realised.

West Derby Rotary Club, Liverpool.

“The Life of William Roscoe – father of Liverpool Culture and founder of, what is today, Liverpool John Moores University. “

A Talk by Lord Alton of Liverpool on Thursday March 29th, 2007.

Exactly 200 years ago this week, the House of Lords, on March 25th 2007, passed the Act of Parliament which abolished the slave trade throughout the British Empire. One month earlier the House of Commons has passed the Bill with 283 Members voting Aye and 16 voting Noe.

Although it would not be until 1833 that slavery itself was made unlawful, the vote in March 1807, followed by enactment on May 1st, represented the culmination of a historic campaign to challenge a deep-seated evil.

between 1701 and 1810 around 5.7 million people were taken in to slavery. Around 39% went to the Caribbean, 38% to Brazil, 17% to South America, and 6% to North America. Many were shipped from the port of Ouidah, on the Bight of Benin. In the millennium year I took to Benin a unanimous statement from the civic authorities in Liverpool recognising the role which Liverpool had played as part of the Triangle of the slave trade. It also contained a commitment to work in these present times for social justice. Since then, thanks to the efforts of the Liverpool sculptor, Stephen Broadbent, works of sculpture, the Reconciliation Statues, have been erected at the three points of that infamous triangle – the last will be unveilled this week in Richmond, Virginia.

To coincide with the bicentenary of the parliamentary vote on abolition, a new film, “Amazing Grace”, has recently been released. It tells the story of William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Ouidah Equiano and John Newton. It is an inspiring story and the film is worth seeing, but it is not the whole narative.

Tonight I want to tell the story of one of the abolitionists who deserves to be better known: it is the story of William Roscoe, a principal friend an ally of William Wilberforce. As Liverpool’s Member of Parliament when the crucial vote was taken, his courageous actions help to redeem our city’s reputation – a reputation which was mired in the commerce of the slave trade.

Sir James Picton, Liverpool’s greatest historian, said of William Roscoe:

“No native resident of Liverpool has done more to elevate the character of the community, by uniting the successful pursuit of literature and art with the ordinary duties of the citizen and man of business.”

So Who Was William Roscoe?

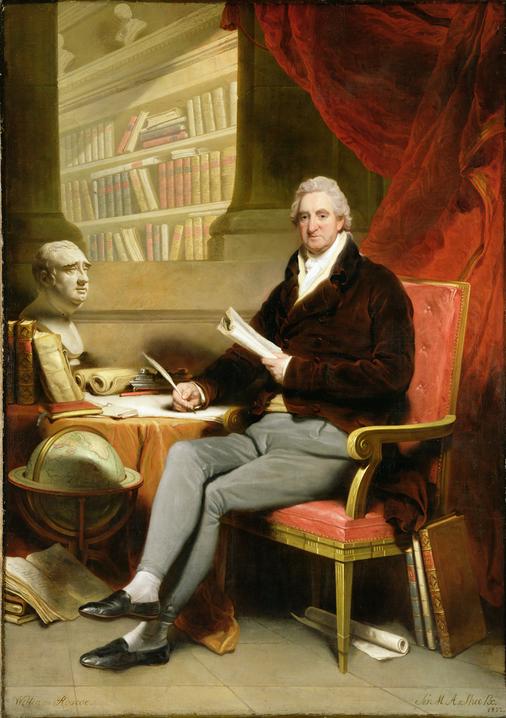

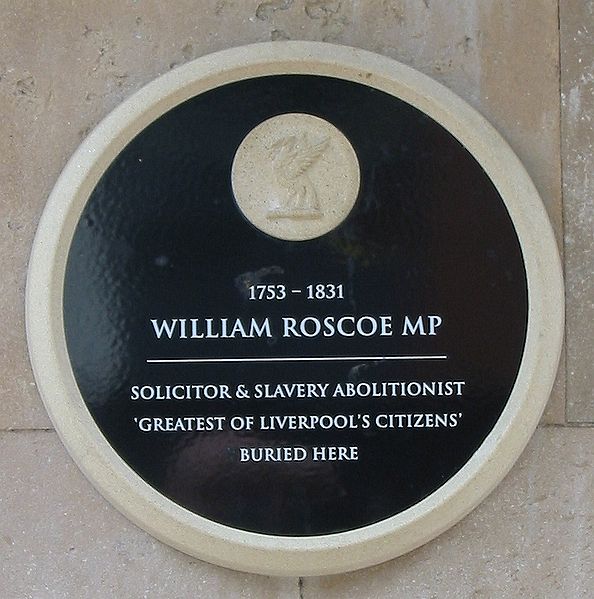

William Roscoe was born on March 8th, 1753, in Liverpool’s Mount Pleasant and that is where he was laid to rest when he died in 1831.

He was the only son of William and Elizabeth Roscoe. A reformer, poet, educationalist, historian, botanist, doyen of the arts, lawyer and banker, Roscoe was

that rarity of men, a polymath.

It was his mother who gave Roscoe his early education, instilling in him a lively interest in poetry and literature, encouraging him to read an 18th century periodical called “Library in Prose and Verse” -learning selected pieces of poetry by heart. Roscoe’s son, Henry, tells us that from early childhood his father developed a profound distaste for both compulsion and coercive restraint in education.

Between 1759 and 1761 he attended a day school in Paradise Street, kept by a Mr.Martin and between 1761 and 1765 a school, also in Paradise Street, kept by Mr.Sykes.

Although he ended his formal education at the age of twelve, and spent long hours working in his father’s market garden growing potatoes; this significantly was also when he bought his first book. This book was to form the core of what subsequently became a world-famous library. Perhaps it was this love of books which led him into his next job, working in a book store.

Through his friendship with Hugh Mulligan, a painter and engraver, he began to develop an interest in the fine arts and from Mulligan – his early mentor – he also learnt how to construct a book case to house the books he had begun to collect.

By the age of 20 with the help of another acquaintance, Francis Holden, with whom he became friendly while a clerk, he had taught himself a reading knowledge of Latin, French, and Italian. He taught himself to etch and he acquired a love of the fine arts.

Roscoe spent his entire life cultivating learning: learning for a purpose. His love of Italian art and literature, in particular, is clear fro the collections of books and drawings held in Liverpool Central Library and the Walker Art Gallery.

Through his membership of the city’s Unitarian chapel he also developed a life long love of the Scriptures, which he wrote about in one of his early works. Roscoe was a member of the Unitarian Chapel at Benn’s Garden, the forerunner of the Renshaw Street Chapel – and his Unitarian faith continues to be celebrated at the Unitarian Chapel in Ullet Road, which houses many of his artefacts. His outlook, as a dissenter – which made him an “outsider” – would influence many of his views. When he was offered the deputy lord lieutenancy of the County, for instance, he refused to take it because appointment was reserved for members of the established Church and, despite a willingness to overlook his Unitarianism, he said that bad laws should be repealed not overlooked.

His view of the law – a profession which he later said had disappointed him – led in 1769 to his being articled to Mr.John Eyes, a Church Street solicitor. He was admitted as an attorney in 1774, and called to the bar at Gray’s Inn in 1797, where he was a member for one term.

With the confidence of a young professional man, sensing security and a future, he found time to woo Jane, the daughter of William Griffies, a Liverpool linen draper, and they married on February 22nd 1781. they moved to the nearby countryside, the Dingle, in Toxteth Park, where, as he wrote;

“.the linnet chirps his song.

And bending tufts of grass,

Bright gleaming through the encircling wood,

.grateful for the tribute paid,

Lordly Mersey loved the Maid.”

In 1773, now aged 20, Roscoe founded “A Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Painting and Design” and in 1775 Roscoe organised the first exhibition of painting ever held in Liverpool, or indeed any provincial city or town. The exhibition mainly featured the paintings of local artists.

In 1783 he and some friends inaugurated another society – one which organised a series of public lectures with the objective of educating public taste. Roscoe delivered the first of these lectures himself. I wonder what he would make of the Roscoe Lecture series, now in its tenth anniversary year, and established by the Foundation for Citizenship at Liverpool john Moores University, which has staged more than 65 lectures in Roscoe’s name. Often attracting audiences of over 1,000 people, these lectures have been given by significant figures from the worlds of politics, law, religion, academia, culture and the arts; and lecturers have included His Holiness the Dali Lama, the Presidents of Ireland and Ghana, and senior Cabinet Ministers. He would surely have approved of their common theme of “citizenship.”

This Liverpool Academy was later taken under the wing of the Liverpool Royal Institution which Roscoe helped pioneer in 1817. The Academy was to be place of learning imbued with the explicit objective and ideal of contradicting the lust for money which had become the hallmark of Liverpool’s commercial life.

This happy period of his life was also when he began to make a mark as a poet and pamphleteer, using his professional skills to enter the world of literature and politics.

In 1777 and 1787 he published pamphlets against the slave trade – an extraordinarily brave thing for a young man to do in Liverpool as it could quite easily have destabilised and jeopardised his own early career and professional interests.

Roscoe later wrote poetry which expressed sympathy with the French revolution and in 1796 he used a pamphlet to attack what he saw as the complacency of Edmund Burke. Roscoe believed that reform of Britain’s institutions was threatened by scare-mongering about revolution overseas.

One year earlier he had penned a letter to the Marquess of Landsdowne, in which he bitterly took issue with Pitt’s legislation dealing with the “terrorist” threat of his day. He thundered that Pitt was creating a country in which “every man is called upon to be a spy upon his brother.”

Roscoe was a devotee of Italian Renaissance history. His widely acclaimed biography of Lorenzo de’Medici led Horace Walpole to describe him as “the best historian and poet of this age” and it gave Roscoe the idea of trying to turn Liverpool into another Florence. How fitting that we should revisit his life on the eve of Liverpool’s achievement in becoming the European Capital of Culture. However, the last decade of the eighteenth century was not so favourable to such a sentiment, and in the heat of the fearful anti-Jacobin feeling engendered by the French revolution, Roscoe and his friends were forced to close down their Literary and Philosophical society. It was seen as a dangerous and threatening presence.

In the soured atmosphere of British-French antagonism he observed that “the present war is not a war against the French but a war of the English aristocracy against the friends of reform in this country.”

Just before the turn of the century, in 1799, Roscoe purchased Allerton Hall – where the natural beauty of his surroundings would later provide the inspiration for “The Butterfly Ball” – a perennial favourite, which King George III had set to music. In the same year he and a group of friends created a scholars’ library, the Liverpool Athenaeum. The club still houses a collection of Roscoe’s books and fittingly, the Roscoe share of the Athenaeum, is today owned by the first West African member, Tayo Aluku, an architect. In addition, in 1802 the city’s Botanic Gardens were established, initially in Mount Pleasant and later moved to Botanic Road. Roscoe invited the celebrated botanist, Sir James Edward smith to open the Gardens and it was from specimens held in the Gardens that sketch and coloured plates – many in roscoe’s own hand – were drawn and exhibited widely. Roscoe was a very early “Green” and his fame as a naturalist led to the plans for the Liverpool Botanic Gardens being copied in places as far away as Calcutta and Philadelphia.

This flurry of activity recalls the classical age encapsulated by Cicero’s belief that it is through activity that virtue is cultivated. Roscoe was most certainly a virtuous and good man; he was also becoming more emphatic in his political views.

1802 brought the publication of a pamphlet in which he deplored the possibility of any resumption of hostilities with France. In March 1805 he wrote to the government condemning their punitive policy towards Irish Catholics. He demanded a “general toleration” of dissenting religious belief and he felt increasingly attracted to the abolitionist cause. None of these opinions seemed likely to please voters in his native Liverpool and it must have seemed unlikely when he was chosen, late in the day, as the Whig candidate in the 1806 election, that he would achieve widespread support.

Against the odds Roscoe was elected to the House of Commons for the Liverpool constituency.

One of his contemporaries, Francis Horner, a colleague in the short-lived Whig administration – the so-called “Ministry of all the Talents” – described him as “a fine looking tall man, with an impressive countenance.rather farmer looking.completely idolised here by all ranks. Besides his bank, which he attends four complete days each week, he has two large farms. He writes his books, collects pictures and etchings, reads a great deal, and makes plans for all the public buildings. In short he is a most surprising, worthy, agreeable, and respectable man…”

Lady Elizabeth Holland, wife of the Lord Privy Seal, recorded a less complimentary evaluation of Roscoe’s persuasive powers as a parliamentary orator, writing on January 7th 1807, when she recorded that:

“Roscoe spoke yesterday for his maiden speech. Windham says his manner is dull, coarse and provincial. I do not think that his talents are such as will enable him to add

to his reputation by his public speaking.”

Be that as it may, his speech, one month later, on February 23rd, would be the speech for which he would be remembered; and for which he would suffer at the hands of his constituents. William Wilberforce and his supporters told him that his speech and his vote were worth twenty of anyone else’s because Roscoe would have to pay a price.

This was the very first time that a Liverpool member had spoken out against the slave trade in the House of Commons and he spoke up clearly, demanding outright abolition.

In scrutininising Hansard today the contemporary reader may be left uncomfortable by two aspects of that speech; although it is always slghtly disingenuous for modern audiences not to view issues in the context of the times.

First, he defended his constituents from the charge that they had connived in inhuman and degrading acts and secondly he argued for compensation for the slave owners. Like Wilberforce and all the others he never argued for compensation or redress for those who had been enslaved. This led to the charge that even he was not free from what was sometimes described as “a degree of Liverpool taint or temporising at least.”

It is doubtful that Roscoe believed that the call for compensation would be enough to either appease his constituents or endear him to them. Compensation was ultimately approved by Parliament, in 1833, when the practice of slavery, as distinct from the slave trade, was itself ended. This led to the bizarre and historically uncomfortable payment of large sum by the State to august institutions such as the Church of England and academic foundations.

Roscoe knew that the Liverpool merchants were not, in 1807, about to be bought off with offers of compensation and he must have been well aware of the reception which would await him on his return to his city.

After all, this was the man who had published polemical tracts and poems, not only denouncing the inhumanity and innate evil of slavery but who had also warned those who connived in the trade that they would face eternal damnation.

In his poem, The Wrongs of Africa, published in 1787, he wrote of the iron hand crushing the people of Africa. He devoted the proceeds of the poem to the London Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

“Blush ye not

To boast your equal laws, your just restraints,

Your rights defined, your liberties secured,

Whilst with an iron hand ye crush to earth

The helpless African; and bid him drink

That cup of sorrow, which yourselves have dashed,

Indignant, from oppression’s fainting grasp.”

The final stanza of Part One of this 35-page poem warns its readers, with great strength and poignancy:

“Forget not, Britain, higher still than thee

Sits the Judge of Nations, who can weigh

The wrong and can repay. Before His throne

Confess they weakness; nor with impious voice

Arraign th’ immutable decree, that fix’d

The bounds of wrong and right; that gave to all

Their equal blessing, and secures its ends

By penalties severe; which often slow,

But always certain, on the guilty head,

Pour down the terrors of the wrath divine.”

In February 1807 the poet had the opportunity to turn his verse into parliamentary prose:

Hansard records, on February 23rd 1807, that:

“Mr.Roscoe declared, that, after having performed the great duty of abolishing the slave trade, which had so disgraced the land, he thought the House bound to consider the situation of those who should suffer from the annihilation of a system so long sanctioned by the Legislature.”

In his speech Roscoe tried to balance what he described as “satisfying both his own feelings and the duty he owed to constituents,” a dilemma with which any of us who have served as Members of Parliament are more than familiar.

He was proud that Liverpool was not wholly in the pocket of the slave owning interests, declaring to the House of Commons:

“Whatever might be supposed, the inhabitants of the town of Liverpool are by no means unanimous in resisting the abolition of the slave trade.”

He argued that a benevolent policy would lead to an increase in the numbers of workers in the settlements, declaring:

“It would banish that horrid maxim so familiar on the islands” (the West Indies)”that it is better to buy than to breed slaves; and the principles of humanity would be so fortunately blended with the notions of commercial policy, that the felicity of that unfortunate class of beings would be finally consulted.”

The principle that it is better to breed workers to run the sugar plantatons rather than buy and sell them is also a principle with which we should feel decidely uncomfortable.

But, Roscoe was walking a tight rope, trying to weigh humanitarian objectives alongside those of his constituents’ commercial self-interest. He argied for gradualism: “I hope the merchants of Great Britain will find in a more extended commerce, a more lasting compensation than a pecuniary one can bestow.”

Yet, even as he argued for gradualism and compensation for those whose commercial interest would suffer – in a city where the Liverpool historian, Ramsay Muir, estimated that around £15 million passed hands in 1807 – a phenomenal sum in those days – Roscoe’s fundamental principles could not for long be concealed.

Hansard says:

“He could not help strongly condemning that branch of this disgraceful traffic, which supplied the Africans on the coast with the means of vice and debauchery, in furnishing them with brandy and fire arms in exchange for their slaves.”

He raised the anxiety that slaves who had already been captured and who would be brought to the coast, finding no buyers, their captors “might massacre them on the shores of their country. Feeling this apprehension, he enquired what would be the time necessary to apprize the native slave merchants and prevent this calamity, and he was told that a notice of six or nine months was competent for the purpose.”

He concluded his remarks with a forthright condemnation of the trade itself:

“I have, said the hon.gentleman, long resided in the town of Liverpool; for 30 years I have never ceased to condemn this inhuman traffic; and I consider it the greatest happiness of my existence to lift up my voice on this occasion against it, with the friends of justice and humanity.”

The price which Roscoe paid for lifting his voice was considerable. He returned to Liverpool on May 2nd 1807, the day after the abolition of the trade became law. His public entry was disastrous. A combination of enraged slave traders and religious zealots – who reviled Roscoe because he had championed Catholic relief – assailed Roscoe as he stepped from his coach and horses in the city’s Castle Street.

Although he would never be returned to Parliament again, Lord Holland, not only spoke for his Cabinet colleagues, but for many sympathisers of the Whig cause, when he wrote to Roscoe to say that his “rejection at Liverpool is considered by us all as one of the greatest disgraces to the country, as well as misfortunes to the party, that could have happened.”

Ahead of his time, politically, he never deserted the Whig cause. At the subsequent General Election he supported the unsuccessful Henry Brougham (immortalised in Liverpool’s Brougham Terrace) against the Tory, George Canning, who would become Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister, paradoxically, coming to rely on Whig support to prop up his ailing Administration.

Canning and other great political figures of this age – such as William Huskisson, who also sat in Parliament as a Liverpool MP – although from the other side of the political divide -, would come to thoroughly embrace Roscoe’s views on issues such as slavery and Catholic emancipation.

A man who was ahead of his time; sometimes a prophetic voice; Roscoe passionately believed in the cause of reform as a way of defeating social unrest and even revolution:

in a letter to Henry Brougham we gain an interesting insight into his thinking, his desire to try and find middle ground and middle ways.

He explained his philosophy thus:

“I consider myself in some degree as a sort of connecting link

Between the more aristocratic and democratic friends of our cause, and if I were to give way to every popular impulse I should not only act against my own feelings, which revolt at all extremes, but do essential injury to the cause.”

In so many respects Roscoe was indeed a “connecting link.”

If he was a connecting link between aristocrats and democrats, and to Liverpool’s Whigs and Tories of the early ninetieth century, he was also a link to the great figures of the Victorian age.

The Liverpool born Tory MP, William Gladstone, whose family home was in Rodney Street, who, having voted for slavery, came to renounce it and crossed the floor, becoming Liberal Prime Minister four times. His Chief whip was the Liberal Member of Parliament for Liverpool, William Rathbone VI, whose grandfather, William Rathbone IV, a Quaker, had been a founder, with Roscoe of the Liverpool Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

In another connecting link to Liverpool’s twenty-first century status as a city of learning, and capital of culture, while the Rathbone family founded Liverpool University, Roscoe, with three other businessmen, founded an Institute for Mechanics and Apprentices, which has today evolved into the thriving Liverpool John Moores University.

That university’s most recently awarded honorary fellowship was given to President John Kufuor, the President of Ghana and Chairman of the African Union. Roscoe would doubtless see a fitting and happy connecting link with his leonine efforts to free West Africa from the curse of slavery.

Roscoe’s rejection in Liverpool brought his foray into parliamentary politics to an abrupt end.

Was it serendipity or providence that in the few months during which he sat for the Liverpool seat the defining vote on the slave trade had taken place?

Either way, his actions and his words do something to redeem that bleak and dark period of our city’s history and reputation. Although he was an opponent of the Tory, Edmund Burke, we can perhaps see the truth of Burke’s famous aphorism that evil triumphs when good men do nothing vividly proven in the life of this virtuous and singular man. His was truly “a good deed in a naughty – not to say, wicked – world”

His rejection at the polls did not bring his campaigning and good works to an end.

Soon after his defeat he helped create the London-based African Institute to celebrate the people and culture of that great continent.

When the citizens of this city rejected him he once again turned to the solace of learning, saying: “let us again open the book of nature and wander through the fields of science.”

His refusal to be crushed was expressed later in that same year, 1807, when he wrote and published his wonderful poem “The Butterfly Ball and The Grasshoppers” Feast “, which set a trend in children’s picture books, and it sold more than 40,000 copies.

It was originally written to appease his young son, Robert – around whom the poem is written. Robert was cross at being excluded from a dinner to which his father had been invited. The poem was his consolation prize. Sir George Smart set it to music for the young princesses Elizabeth, Augusta and Mary.

It is worth revisiting here:

William Roscoe (1753-1831)

The Butterfly’s Ball, and the Grasshopper’s Feast

1Come take up your Hats, and away let us haste

2To the Butterfly’s Ball, and the Grasshopper’s Feast.

3The Trumpeter, Gad-fly, has summon’d the Crew,

4And the Revels are now only waiting for you.

5So said little Robert, and pacing along,

6His merry Companions came forth in a Throng.

7And on the smooth Grass, by the side of a Wood,

8Beneath a broad Oak that for Ages had stood,

9Saw the Children of Earth, and the Tenants of Air,

10For an Evening’s Amusement together repair.

11And there came the Beetle, so blind and so black,

12Who carried the Emmet, his Friend, on his Back.

13And there was the Gnat and the Dragon-fly too,

14With all their Relations, Green, Orange, and Blue.

15And there came the Moth, with his Plumage of Down,

16And the Hornet in Jacket of Yellow and Brown;

17Who with him the Wasp, his Companion, did bring,

18But they promis’d, that Evening, to lay by their Sting.

19And the sly little Dormouse crept out of his Hole,

20And brought to the Feast his blind Brother, the Mole.

21And the Snail, with his Horns peeping out of his Shell,

22Came from a great Distance, the Length of an Ell.

23A Mushroom their Table, and on it was laid

24A Water-dock Leaf, which a Table-cloth made.

25The Viands were various, to each of their Taste,

26And the Bee brought her Honey to crown the Repast.

27Then close on his Haunches, so solemn and wise,

28The Frog from a Corner, look’d up to the Skies.

29And the Squirrel well pleas’d such Diversions to see,

30Mounted high over Head, and look’d down from a Tree.

31Then out came the Spider, with Finger so fine,

32To shew his Dexterity on the tight Line.

33From one Branch to another, his Cobwebs he slung,

34Then quick as an Arrow he darted along,

35But just in the Middle, — Oh! shocking to tell,

36From his Rope, in an Instant, poor Harlequin fell.

37Yet he touch’d not the Ground, but with Talons outspread,

38Hung suspended in Air, at the End of a Thread,

39Then the Grasshopper came with a Jerk and a Spring,

40Very long was his Leg, though but short was his Wing;

41He took but three Leaps, and was soon out of Sight,

42Then chirp’d his own Praises the rest of the Night.

43With Step so majestic the Snail did advance,

44And promis’d the Gazers a Minuet to dance.

45But they all laugh’d so loud that he pull’d in his Head,

46And went in his own little Chamber to Bed.

47Then, as Evening gave Way to the Shadows of Night,

48Their Watchman, the Glow-worm, came out with a Light.

49Then Home let us hasten, while yet we can see,

50For no Watchman is waiting for you and for me.

51So said little Robert, and pacing along,

52His merry Companions returned in a Throng.

We can imagine William Roscoe, sitting before a blazing fire, close to the hearth at Allerton Hall, s surrounded by his seven sons and two daughters, reciting The Butterfly Ball and its sequel, The Butterfly’s Birthday , written in 1809, or one of his many odes or hymns.

He took his duty to educate his children very seriously; but that duty didn’t end there. During his brief time in Parliament he supported Whitbread’s campaign for popular education – a cause which would be taken up by Lord Shaftesbury, through his ragged schools, and by Gladstone, through his Education Act in 1870.

Roscoe passionately believed in education as the ladder up which each man and woman could climb. As well as largely educating himself, in maturity Roscoe took personal responsibility for the education of several young people. These included young girls, again demonstrating how far he was ahead of his times, and children who had no means of supporting themselves but who clearly had potential and talent.

In one of his poems he celebrated the life of a young Welsh fisherman whom he helped, Richard Robert Jones, who had learnt Greek, Latin and Hebrew as well as French and Italian. He supported two orphaned families as well as his own children.

His achievements as a writer led to his election, in 1819, as an honorary member of the Royal Society of Literature – and whether he is measured by honours such as these – or by the bequests and initiatives which endowed our museums, libraries and galleries, the foundation of the Botanic Gardens, The Liverpool Athenaeum, or educational institutes which would ultimately evolve into modern centres of learning, such as Liverpool John Moores University, it is no exaggeration to say that by the time of his death in 1831, William Roscoe had laid the foundations for some of the city’s finest educational and cultural ventures.

In yet another connecting link how fitting it is that 2008 will see Liverpool as European Capital of Culture.

Without doubt, the man who was father of Liverpool’s culture was William Roscoe, and without those foundations laid 200 years ago, Liverpool would never have been able to attain this significant status.

In 1815 Roscoe was made a Freeman of the city of Liverpool – and his election was accompanied by a triumphal procession, which perhaps mitigated some of the events and popular repudiation of 1807. His personal fortunes, however, did not prosper, and in 1820 he had to sell his personal effects to stave off bankruptcy. His friends generously secured many of his books and works of art and this enabled him to live the rest of his life in modest comfort but it also enabled the collections which he had so dearly prized to be retained in the city for posterity.

In 1831, on June 30th, aged 78, Roscoe succumbed to influenza and died. He was interred in the burial ground abutting Renshaw Street Chapel, close to where he had been born at the Old Bowling Green House Tavern in Mount Pleasant, and abutting the chapel where had had worshipped. A small monument and garden remain as Roscoe’s memorial and are accessed from Mount Pleasant.

It was a poem of that very name, Mount Pleasant, written in 1777, which was his first published work; and in it he attacked the slave trade and warned the captains of industry and the mercantile classes not to neglect their civic duties or responsibility to work for the common good.

He warns that if we neglect the rights of Man the consequences for his city, the city he loved would be profound:

He wrote:

“The time may come – O distant be the year –

When desolation spreads her empire here,

When Trade’s uncertain triumph shall be o’er,

And the wave roll neglected on the shore and not one trace of former pride remain.”

He mused and challenged with these words:

“Shame to Mankind! But shame to Britons most,

Who all the sweets of liberty can boast;

Yet deaf to every human claim, deny

That bliss to others, which themselves enjoy:

Life’s bitter draught with harsher bitter fill;

Blast every joy, and add to every ill;

The trembling limbs with galling iron bind,

Nor loose the heavier bondage of the mind.

Yet whence these horrors? This inhuman rage,

That brands with blackest infamy the age?

Is it, our varied interests disagree,

And BRITAIN sinks if AFRIC’S sons be free?

-No – hence a few superfluous stores we claim,

That tempt our avarice, but increase our shame;

The sickly palate touch with more delight,

Or swell the senseless riot of the night. –

Blest were the days ere Foreign Climes were known,

Our wants contracted, and our wealth our own;

When Health could crown, and Innocence endear,

The temperate meal, that cost no eye a tear:

Our drink, the beverage of the crystal flood,

-Not madly purchased by a brother’s blood –

Ere the wide spreading ills of Trade began,

Or luxury trampled on the rights of Man.

In summary, let the last word go to George Chandler .

Chandler was the Liverpool’s City Librarian and in 1953 Liverpool City Council sponsored a volume of verse, writings and biography which he was asked to assemble. Chandler said that Roscoe’s legacy comprised “some of the noblest thoughts of that exciting and expanding age of Liverpool’s history…Freedom, equality and toleration were ideals which he followed only in so far as they were not used to justify doing harm to others. For him there was no short cut to the Kingdom of Heaven on earth. The measures he supported were not those of violence but of persuasion, self-discipline and individual effort.”

As we celebrate Roscoe’s legacy today, he would not wish this bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade to be a time for shallow apology or self indulgent self-congratulation. He would be busying himself on behalf of the 27 million people estimated by the United Nations to be enslaved today, including the 8.4 million children held in slavery, and the estimated 700,000 people trafficked annually in the world.

He would surely have been championing the plight of the 167 million Dalits in Indio, enslaved by their caste system, or the peoples of countries like Sudan and Congo, and the victims of genocide in Darfur and Burma. He would want to be a connecting link from his generation to ours in inspiring and challenging us to be men and women for others.

Over the past 200 years many of the successful campaigns for human rights have been modelled on the successful actions of Roscoe and Wilberforce, Wedgwood, Clarkson, Equiano and the others who confronted the greatest evil of their day. It is that same spirit of being a voice for voiceless people that we need today; and what better model can we take than William Roscoe?

A Roscoe Lecture was given on Tuesday June 21st at 5.00, at St.George’s Hall, Liverpool. by Sir Jon Murphy QPM, Merseyside Chief Constable, who reflected on his 40 year career in policing: “Leading A Force For Good Through Stormy Waters”

In 1822, during the last decade of William Roscoe’s life, Robert Peel, the father of modern policing, became Home Secretary.

Peel believed that “The police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence” and it was on the basis of this belief that the concept of “policing by consent” evolved.

Sir Jon Murphy’s outstanding police career –spanning four decades – has been based on the belief that policing by consent means that for the police to be able to fulfil their duties and functions they depend on public approval and respect for their modus operandi, their behaviour, and their conduct.

Policing with the consent and co-operation of the public is what sets us apart from the paramilitary policing of the Police State – which is based on coercion, fear, the trademark knock on the door in the middle of the night.

Policing by consent is the hallmark of a vibrant and democratic civil society which itself cannot be sustained unless the rule of law is upheld; it confers legitimacy and guarantees accountability.

Although he read Law at Liverpool University, has a postgraduate Criminology Diploma from Cambridge and in 1995 was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship Jon learnt about policing the hard way, in the university of adversity.

He began his policing career as a cadet in 1975 and served on the front line during the Toxteth Riots of 1981 – which followed the arrest of a young black man Leroy Cooper on July 3rdof that year. In the days which followed hundreds of police officers were injured, 500 arrests were made, and many buildings were set on fire.

The riots were a test of “policing by consent” and led to more focused community policing.

Shortly after the riots Jon entered the CID and after nearly 20 years as a detective, achieving the rank of Detective Superintendent SIO, he returned to uniform as Forces Operations Manager and then attended the Strategic Command Course.

In 2001 he was appointed Assistant Chief Constable, Head of Operations and gained international experience through the creation of the first European Joint Investigation Team.

In 2004 he returned to Merseyside as Deputy Chief Constable and three years later the then Home Secretary asked him to lead the Ministerial Task Force – ‘Tackling Gangs Action Programme’. In 2008 he was given further nationwide responsibilities in tackling serious crime.

His extraordinary and remarkable range of policing experiences, from Bobby on the Beat to crime solving detective; from front line riot control to tackling gang culture; from ministerial advisor to national coordinator of the response to organised, serious crime; from collaborative work with police in Europe and in the USA, in 2010 Jon Murphy was clearly the perfect choice to be appointed Chief Constable of Merseyside Police.

Remarkably, too, Sir Jon has been commended on fourteen occasions and, in 2007, Her Majesty the Queen awarded him the Queen’s Police Medal, followed, in 2014, by a Knighthood.

Sir Jon has a long and distinguished policing career. As a living exponent of Robert Peel’s principle of “policing by consent” he has developed a formidable and highly prized network of civic and community relationships – not least with the city’s academic community, recognised, in 2014, by the award of an Honorary Fellowship by Liverpool John Moores University.

With apologies to W.S.Gilbert, “a policeman’s lot may not always be a happy one”, but, as they seek to uphold the rule of law, the thin blue line is often all that separates society from chaos and criminality.

As he leaves his post as Chief Constable we are delighted that he will use this valedictory Roscoe Lecture to reflect on his important and remarkable achievements and to look at the challenges which confront the next generation of police officers.

Liverpool John Moores University and a talk by Chief Constable of Merseyside Police Sir Jon Murphy

————————————————————————-

On June 2nd John Studzinski CBE, investment banker and philanthropist gave a Roscoe Lecture entitled “Making Money To Do good Things.”

TO LISTEN TO THE LECTURE GO TO:

https://www.ljmu.ac.uk/about-us/roscoe-lecture-series/previous-lectures/nineteenth-series

————————————————————————–

On May 19th the 139th Roscoe Lecture was delivered by the Speaker of the House of Commons, the Rt,Hon John Bercow MP:

TO LISTEN TO THE LECTURE GO TO:

https://www.ljmu.ac.uk/about-us/roscoe-lecture-series/previous-lectures/nineteenth-series

When in January 1642, King Charles I entered the House of Commons to seize five ‘disruptive’ members, Mr.Speaker Lenthall famously responded “May it please your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here”.

Many of the liberties and freedoms which we cherish – not least, freedom of speech – were defined in the days of Speaker Lenthall and in the Civil War which ensued.

To this day, when the House of Commons elects a new Speaker the successful candidate is supposed to show reluctance as he is dragged to the chair – reminding Mr.Speaker of the dangers that accompany the duties bestowed on the holder of this high office

Although the formal office of Speaker is held to date from the Good Parliament, of 1376, Peter de Montfort is identified, in 1258, as “presiding” over a meeting of Parliament – held in Oxford.

Mr.Speaker Bercow’s historic office has been shaped by the tempestuous events of nearly 1,000 year.

More than 150 men – including Sir Thomas More – and one woman – Betty Boothroyd – have served as Speaker. Their names are inscribed in gold leaf on the upper walls of Room C in the House of Commons library.

During the 19th century – as the present Houses of Parliament were rebuilt and designed by Sir Charles Barry and W.A.Pugin – Mr.Speaker’s role also evolved.

Its holder would eschew party political affiliations and be judged on their impartiality, their fairness, and their determination to champion parliamentary democracy against all the forces which assail it.

Resolutely defending this role, Speaker Bercow insists that dissenting voices must be heard: “Fairness is not about statistical equality,”he says.

Mr. Speaker’s primary duty is to keep the House and debates in order. When there is disruption he may have to demand “Order! Order!” – and may “name” and suspend Members who fail to comply.

Although custom leads to a rotation of contributions from one side to the other, no Member may speak without the Speaker’s permission. If a Division leads to an equality of votes Mr.Speaker may break the tie with a casting vote.

Mr.Speaker has various other duties, including the oversight of the administration of the Houses of Parliament; and remains a constituency MP.

Elected at the beginning of each Parliament by all serving Members, the election is overseen by the Father of the House. At least twelve members must nominate the candidates and at least three of these MPs must be of a different party from the candidate.

John Simon Bercow was elected Speaker in June 2009.

He is the descendent of an Eastern European Jewish émigré family; could have become a professional tennis player; achieved a First Class Honours degree in Government at the University of Essex – where Professor Anthony King described him as “an outstanding student” – had a successful career as a Board Director and in merchant banking; and later established training courses in leadership, communications and public speaking.

He began his political life in Lambeth, in local politics, and was also active within his party’s youth movement

Elected as Conservative MP for Buckingham,in 1997 , and he served in the Shadow Cabinet.

In the Commons he has particularly championed the cause of minorities – including the plight of tribal peoples, and those discriminated against on the grounds of orientation. In 2005, he won the Channel Four/Hansard Society Political Award for ‘Opposition MP of the Year’.

He has a long-standing interest in Burma – and we first met when we shared a platform to highlight the genocidal campaign being waged by the Burmese Army against the Karen and other ethnic groups.

He became known as the most steadfast, devoted, committed, energetic, passionate, loyal and eloquent advocate for the suffering people of Burma and in Parliament was tireless in tabling Parliamentary Questions, initiating Early Day Motions, writing letters to Ministers, seeking and speaking in debates and writing media articles

In 2004 and 2007 he visited the Thai-Burma border – returning as Speaker in 2013 when he pointed to “the release of most political prisoners, greater freedom of expression for the media, increased space for civil society, greater participation in the political process by opposition parties, and the establishment of preliminary ceasefires with most of the ethnic nationalities.”

In 2012 he hosted the visit of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to Westminster – where she addressed both Houses of Parliament – and, after her address, facilitated the bestowment of her LJMU Fellowship in Mr.Speaker’s House.

He has worked hard to restore the reputation of Parliament, arguing that politics needs to be “cleaned up” ;that “a legislature cannot be effective while suffering from public scorn” and that “For far too long the House of Commons has been run as little more than a private club by and for gentleman amateurs”

Passionately believing that politicians and Parliament must re-engage with the people, he says: “ I don’t think that people are disinterested or uninterested in politics. I think very often they are disengaged from the formal political process. To some extent they are suspicious or even despairing of formal politics as a means to give expression and effect to what they want.”Although a Ministerial career and high office were always predicted, he says: “If you asked me if I’d rather be Speaker or a very senior minister, I’d say Speaker.” We are delighted that in his Roscoe Lecture – named for an illustrious Liverpool MP and a founder of what is today LJMU – Mr.Speaker told us why.

————————————————————————

On April 21st Professor Monica Grady CBE gave a Roscoe Lecture entitled “Are we alone?” at St. George’s Hall, Liverpool.,

TO LISTEN TO THE LECTURE GO TO:

https://www.ljmu.ac.uk/about-us/roscoe-lecture-series/previous-lectures/nineteenth-series

When, in 2014, Professor Monica Grady heard the news that the robot probe Philae had landed on a comet, she literally jumped for joy, shed a few tears, and hugged the BBC’s Science Editor, David Shukman –later admitting that her exuberance had got the better of her.

Having been part of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission from its inception Monica Grady’s excitement was understandable. She exclaimed: “It’s landed – I’ve waited years for this”.

Ever since Archimedes discovered the principle of buoyancy while taking a bath, and then, apocryphally, running naked through the streets of Syracuse yelling “Eureka!” (“I have found it!”), the best scientists have combined a patient perseverance with an excited love of their subject. And Monica Grady is no exception.

Currently Professor of Planetary and Space Science at the Open University Professor Grady was born in Leeds, graduated at the University of Durham, and completed her PhD on carbon in stony meteorites at the University of Cambridge. She subsequently curated the UK’s national collection of meteorites at the Natural History Museum where she said she was “like a kid in a sweet shop”. Her published papers include work on Martian meteorites.

In 2000 she was appointed a Fellow of the Meteoritical Society, of which she served as President; is a Fellow of the Institute of Physics; a Fellow of the Geochemical Society; a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society; and delivered the Royal institution Lectures “A Voyage in Space and Time”

Asteroid (4731) was named Monica Grady in her honour and in 2015 she provided Sue Lawley with her selection of Desert Island Discs. Her chosen records included Bat Out Of Hell by Meatloaf, Vienna by Ultravox, and Leonardo Salzedo’sDivertimento – better known as the Open University’s fanfare. Along with a copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the luxury which she wanted to take to her desert island was a flute given to her on her 50th birthday by her husband.

As to life beyond ourselves Professor Grady says life is unlikely to be confined to the Earth even in our own solar system, with comets carrying life’s raw ingredients to different planets: “I think there’s a really, really good chance of finding some type of simple life form.”

In 2012, for her services to science, Her Majesty the Queen appointed Professor Grady a Commander of the British Empire.