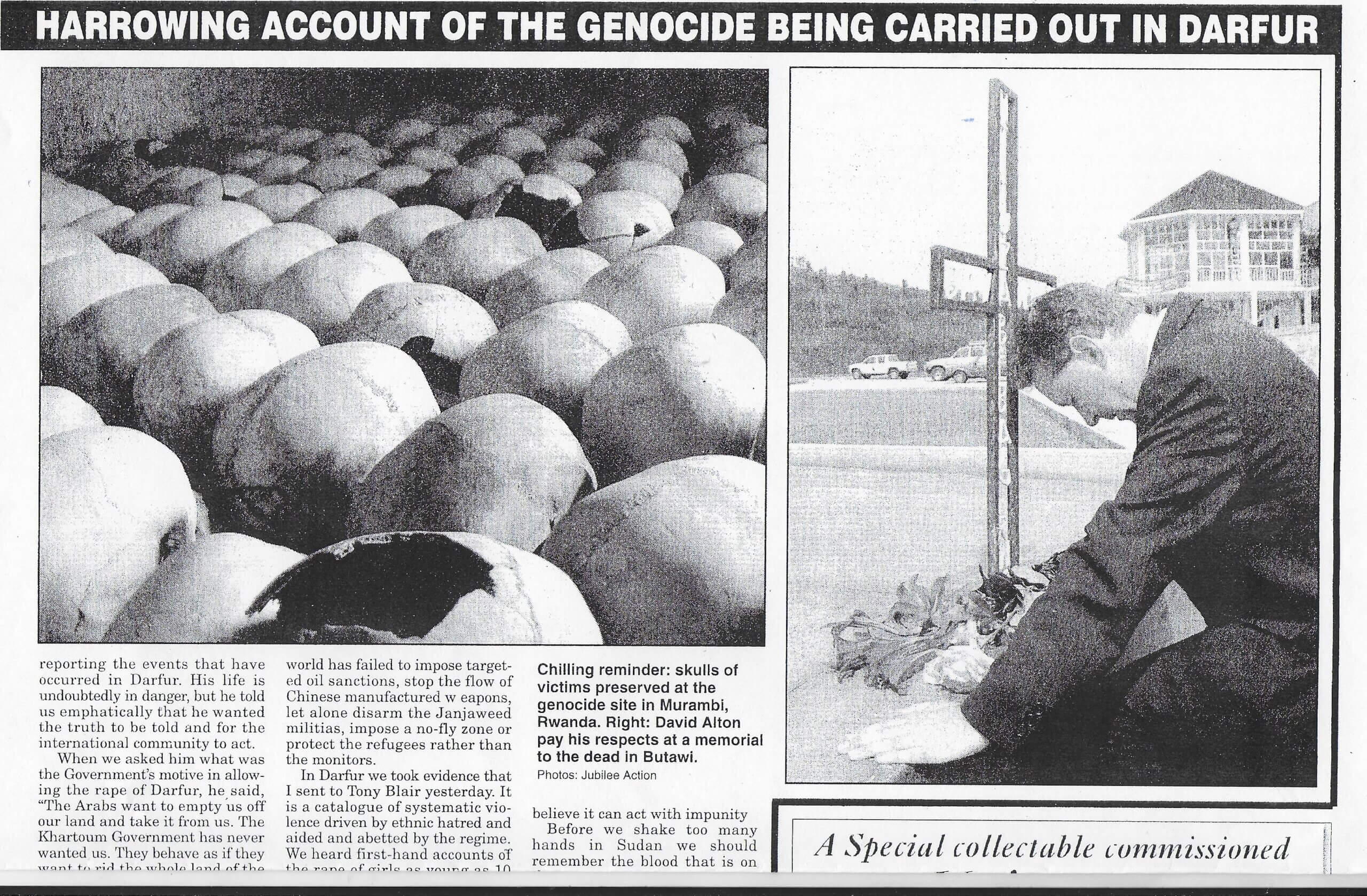

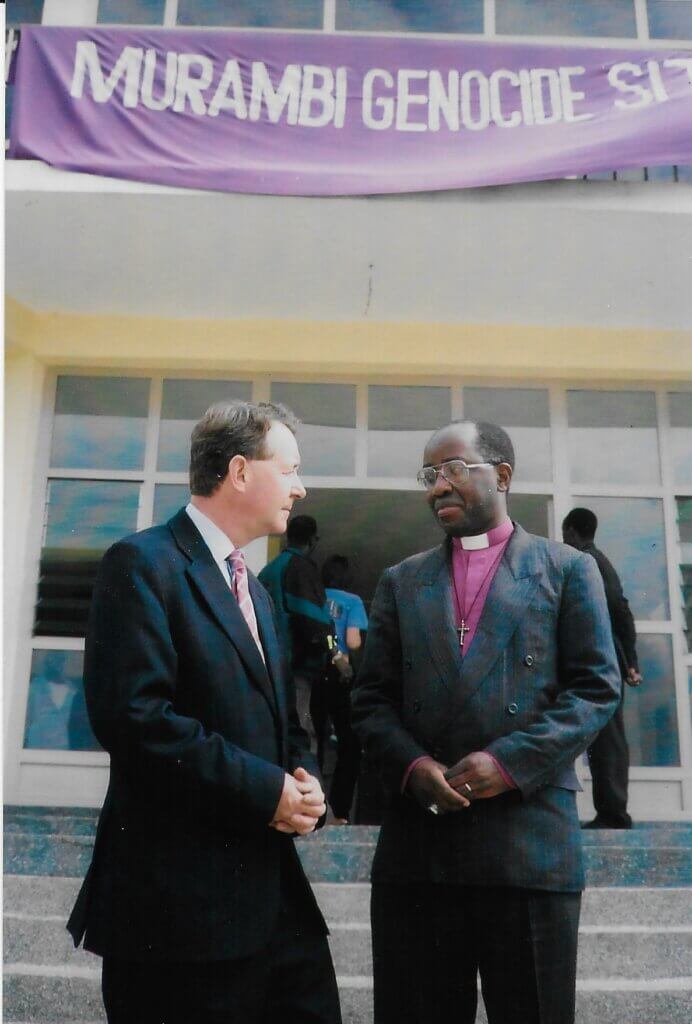

“56,000 bodies were found there, and we walked from classroom to classroom, viewing 852 remains that have been disinterred. Within a few days of the massacre, a volleyball court had been built on top of one of the mass graves which, we were told, the French peacekeepers then used in their leisure time.” What I Learnt at Rwanda’s Murambi Genocide site in 2004 and in Darfur as “never again” happened all over again. David Alton

Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP

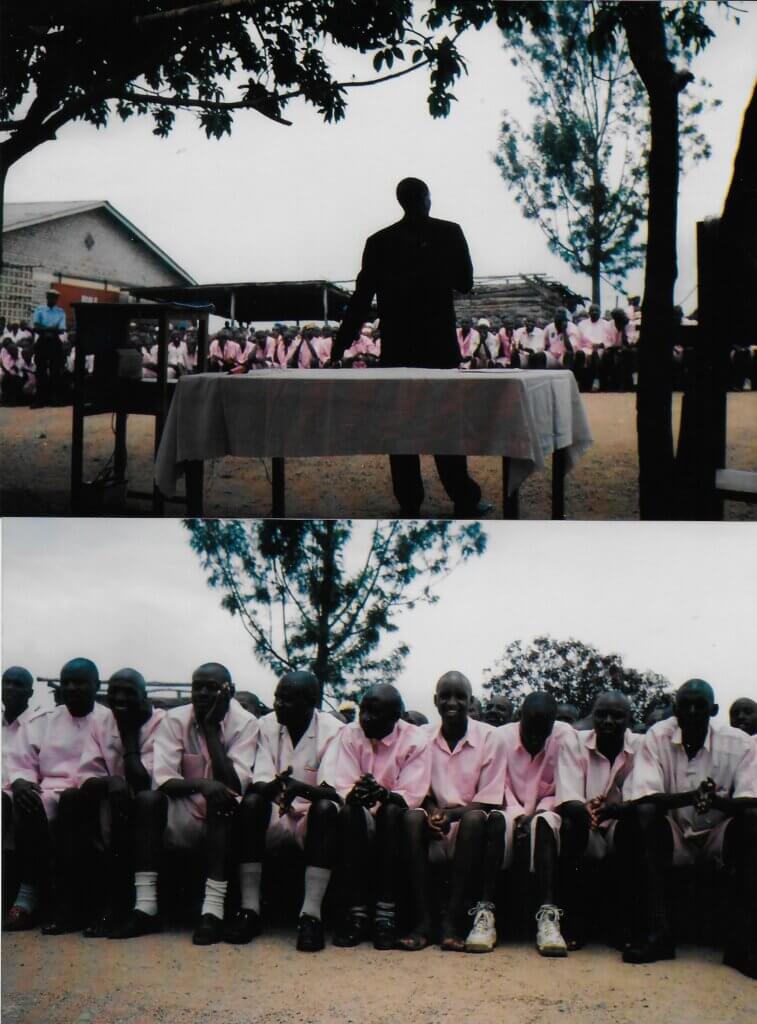

Three years ago, I stood with the wonderful Susan Pollack, the Auschwitz survivor, at the Kigali memorial site in the largest burial ground in the world. We were mourning the million who were slaughtered in a 90-day frenzy of killing and brutality in Rwanda. Most of those who took part have been brought to justice, through either the Arusha international tribunal or the Gacaca courts, which have processed hundreds of thousands who have returned to Rwanda from the hills of the Kivus because they see that the process is decent and fair.

The death penalty in Rwanda has been abolished and most countries—including the United States, Canada, Belgium, Sweden and others—have extradited people back to Rwanda. As John Adams said, “Facts are stubborn things”. Living free in Britain today are five alleged Rwandan genocide perpetrators: three were senior Government officials in the 1994 genocidal regime and one of those was allegedly heavily involved in the notorious massacre of 45,000 Tutsis at Murambi—the worst massacre since the second world war.

On 14 September 2006, the British and Rwandan Governments agreed a memorandum of understanding; I first raised this matter in the House on 5 December 2006. Extradition warrants were signed the same month. In 2015, a British district judge ruled that even though there was a prima facie case of genocide made out against the five individuals, it could breach their human rights to send them back to Rwanda, and that ruling was upheld on appeal. The Rwandan judicial authorities have given up on British justice and extradition and requested that Britain undertake prosecution here. The authorities indicated that the collection of evidence already laid out in the court papers and filed in the UK via the war crimes unit would take up to 10 years to process.

These are the facts. Living in this country today, free and at large for more than 14 years now, are five people accused of the most heinous of crimes: genocide participation—crimes against humanity. Four out of five are living at the taxpayer’s expense and more than £3 million of taxpayers’ money has been spent on meeting their legal fees. Is it any wonder that in Africa, and in the UK, too, people accuse the British establishment of hypocrisy? To them, it looks suspiciously as if crimes against white Europeans are taken more seriously than those perpetrated against black Africans.

I call upon all those who care about the holocaust, genocide and justice to take up this cause. The souls of the slaughtered Tutsis cry out for justice, but Britain has turned a deaf ear. We should all be ashamed.

====================

David Alton: July 2009

Over the past few weeks I have been working with Alex Carlile QC – Lord Carlile of Beriew – to bring to justice people living in the UK who stand accused of genocide in Rwanda. The Justice Minister, Jack Straw, gave the proposal a sympathetic hearing when I met him and the Coroners and Justice Bill provides an opportunity change the law.

When I was in the Commons we passed the War Crimes Act of 1991 – which dealt with suspected Nazi-era war criminals who had secretly entered Britain during the chaos that followed the Second World War.

Alex Carlie made a memorable and moving speech where he began by drawing our attention to what he described as an ‘unregisterable interest’. Two of his grandparents, two of his uncles, an aunt and many cousins were killed during the Holocaust. They were doctors, teachers, postmasters. Normal people murdered because of their racial origins.

The Nazi Holocaust holds a particular horror for the world, and rightly so. That is why Parliament eventually passed the War Crimes Act.

But the victims and survivors of modern genocides and crimes also want justice.

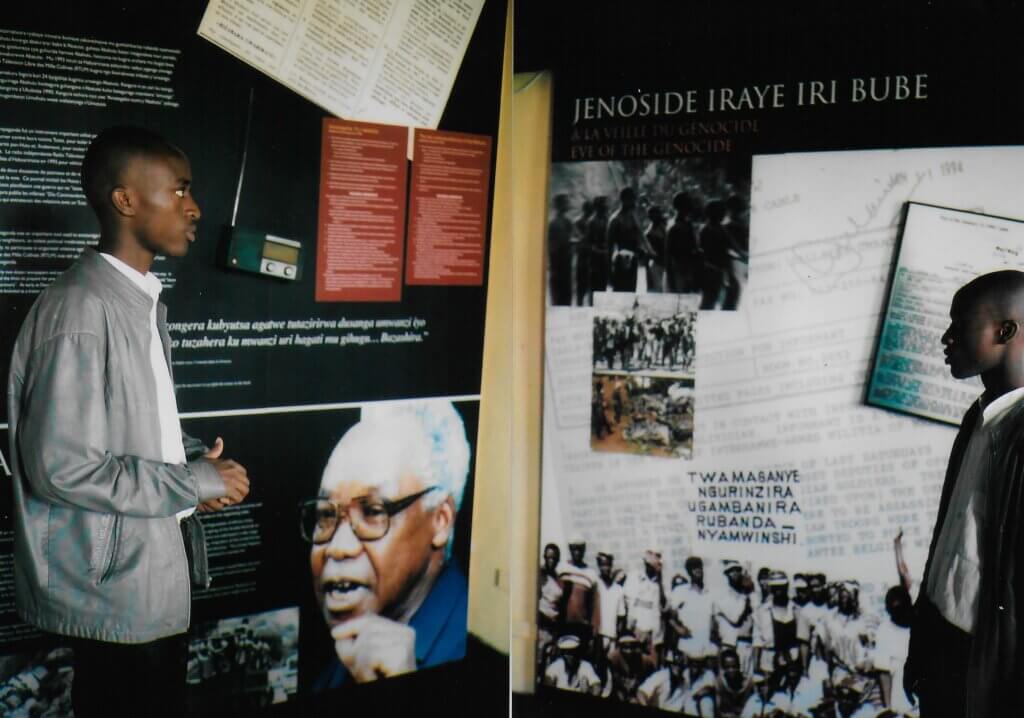

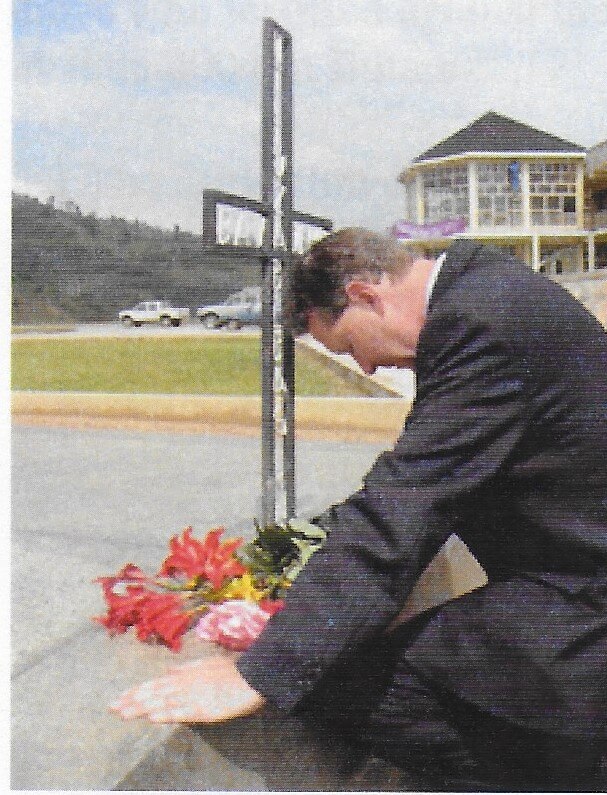

In 2004 I visited Rwanda and published a report which detailed what had occurred at Murambi Genocide Site, which I visited.

Murambi was a technical college in the south west of the country, which I said“served to remind us of the hellish reality of Rwanda’s recent past.”

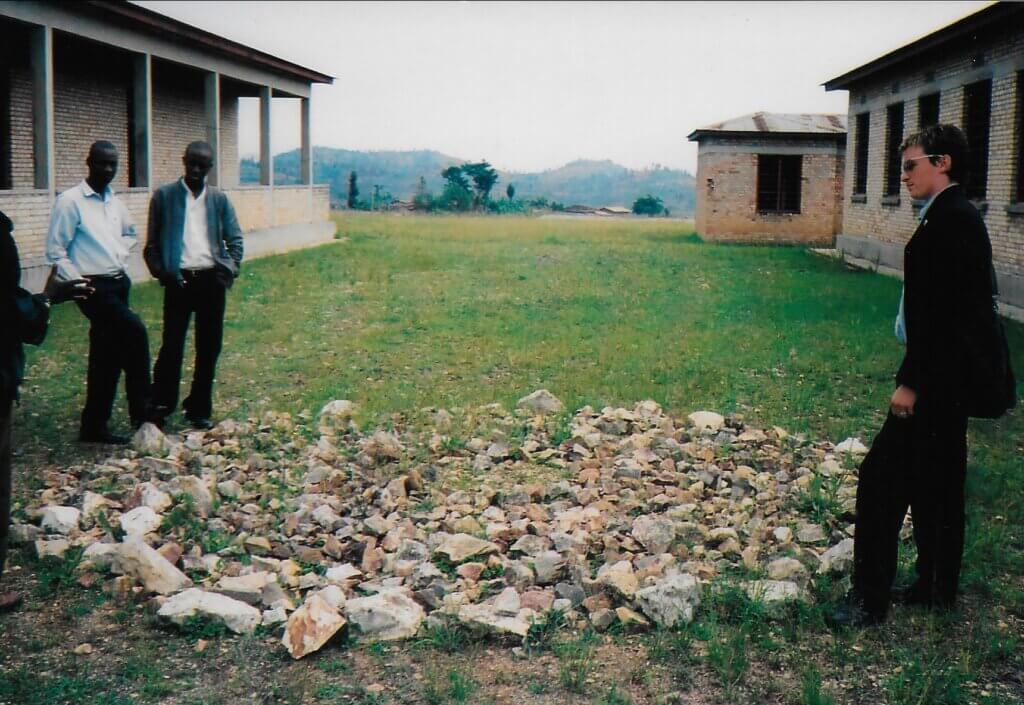

The school is a collection of long single story brick buildings, situated on the top of a hill. There are 66 classrooms in the school.

At the beginning of the genocide many Tutsi Rwandans sought safety in numbers and gathered in churches, public buildings and schools. Thousands of men, women and children – including the children from a nearby orphanage – fled up the hill to Murambi. The authorities told them they would be safe there but then cut off the water and electricity supply. They survived for two weeks until about 3am April 21st 1994.

Then, Interahamwe militiamen (Interahamwe means‘those who work together’) and soldiers arrived and surrounded the school. Armed with guns and grenades they began killing. They killed for over 6 hours. By the morning thousands of civilians were dead. Only four survived, unconscious and left for dead by the murderers.

In my report I described how

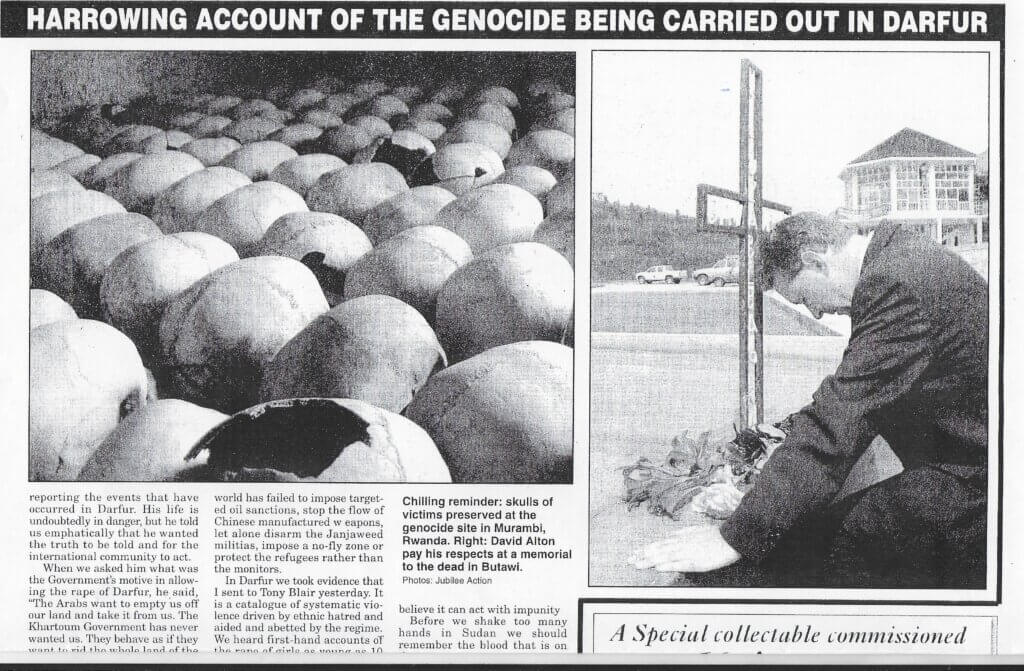

“56,000 bodies were found there, and we walked from classroom to classroom, viewing 852 remains that have been disinterred. Within a few days of the massacre, a volleyball court had been built on top of one of the mass graves which, we were told, the French peacekeepers then used in their leisure time.”

Murambi is now a memorial. Some of the mass graves have been excavated. The classrooms are filled with human remains. In some cases the corpses have been preserved in quicklime and retain tufts of hair and recognisable features. Now in the classrooms lie thousands of white skeletons, sometimes frozen in the positions they fell. It is as if a man-made Pompeii had swept over the hill and through the buildings. Some still clutch their rosaries. Some of the women were clearly pregnant. Skulls bear the marks of the machetes used to hack them down.

It takes a lot of planning to kill thousands of people. Orders must be given for roadblocks to be set up. Petrol must be requisitioned for the vehicles that transport the killers up the hill. Grenades and ammunition must be distributed to the soldiers. Avid killers need to be praised; slackers exhorted to work harder, to kill faster. Genocide is a vast criminal enterprise.

It is alleged that some of those criminals have visited the UK, and some may still be here.

However, due to what the former Director of Public Prosecutions has called jurisdictional gaps, suspects from Rwanda (and perpetrators of some other modern atrocities) cannot be prosecuted here.

We need to make two changes to the law.

We need to retrospectively apply the jurisdiction of the courts to crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes committed before 2001. We should also be able to arrest suspects who visit the UK on holiday or business to be prosecuted.

Rwanda acceded to the Genocide Convention in 1975 – so what happened in 1994 was undoubtedly a crime in the technical sense. The UK put genocide onto its own statute books in 1969. And, of course, genocide has been a crime in customary international law since at least 1948. The issue is not retrospective lawmaking, but the retroactive application of jurisdiction by the UK courts.

One of those accused of the genocide at Murambi is currently living in the U.K. He is accused of transporting interahamwe militia members and bags of grenades to the technical school during the massacre.

These accusations are included in the original ruling by the Westminster Magistrates’ Court. These accusations are also repeated in documents filed at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda; disturbing documents which I have read.

These are allegations. The individual concerned is of course innocent until proven guilty.

And, of course the four suspects who ended up in Britain did not act alone. Indeed, academics estimate that there were up to 200,000 perpetrators. To mobilize, arm and organize such large numbers of killers is a significant undertaking. It also takes significant amounts of money.

One of the key financiers of the genocide is alleged to be Félicien Kabuga. He is still at large and is believed to be in Kenya. He is alleged to have set up a‘Fund for national defence’ – a bank account to which he was a signatory. He is alleged to have been a major share holder in, and President of, RTLM, the hate radio station that read out death lists and directed militia members to where Tutsi were hiding. He and others are accused of buying huge numbers of machetes, perhaps over 500,000, in 1993. An arrest warrant for him has been issued by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda .

It is no exaggeration to say he is one of Africa’s most wanted men. According toThe Times, he has visited Britain:

“At times, Kabuga has even felt secure enough to travel to Europe. One of his journeys has been traced. In 1999 he left Nairobi for Madagascar, travelling on his Kenyan diplomatic passport. Arriving in Brussels on August 12, he held a meeting at the Royal Windsor hotel with several notorious genocide suspects who had flown in especially to see him. Then he went to France and passed briefly through Britain on his way back to Kenya. He also travelled to the Far East on an arms-purchasing mission.”

And Kabuga is not the only one who has been able to evade our laws.

Chucky Taylor, the son of Liberia’s notorious President, Charles Taylor, has recently been sentenced to 97 years by a US court for acts of torture committed while commanding the Liberian president’s Anti-Terrorist Unit.

According toThe Observer he, too, stayed briefly in London.

Men like this should not see Britain as a safe haven or a bolt hole and it’s time we changed the law to bring them to justice.

2005: Queen Speech Debate – speech by Lord Alton

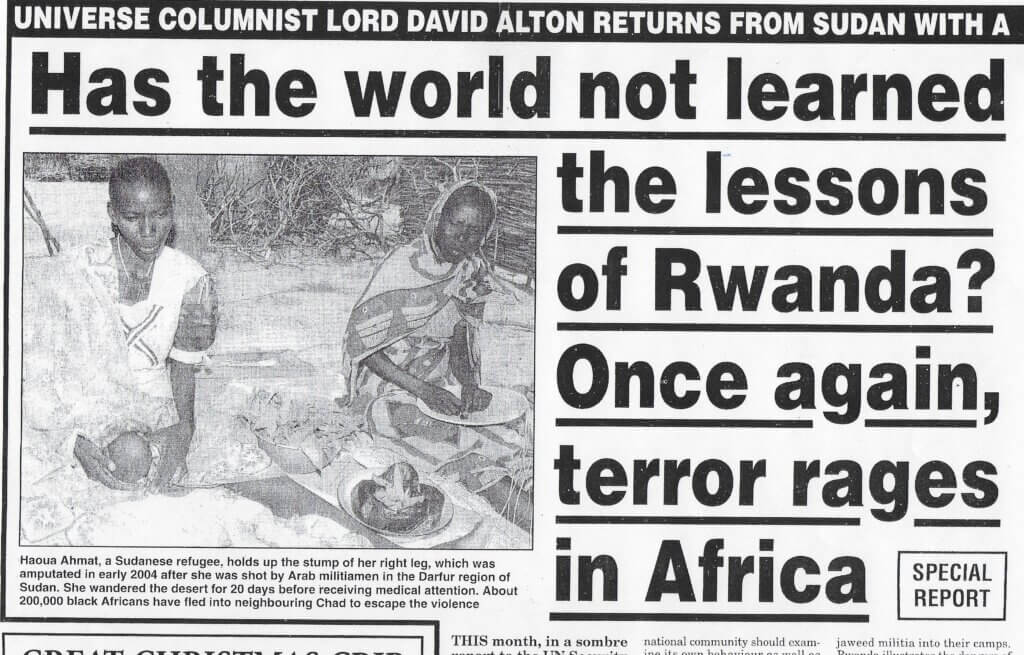

Four years ago, I went to the devastated areas of southern Sudan—so familiar to my noble friend Lady Cox, from whom we will hear later. I saw the ravages of 20 years of killing in a region where some 2 million have died. In November 2004, I detailed my then recent visit to the western province of Darfur. I published a report through the Jubilee Campaign and described in your Lordships’ House what I had heard and seen.

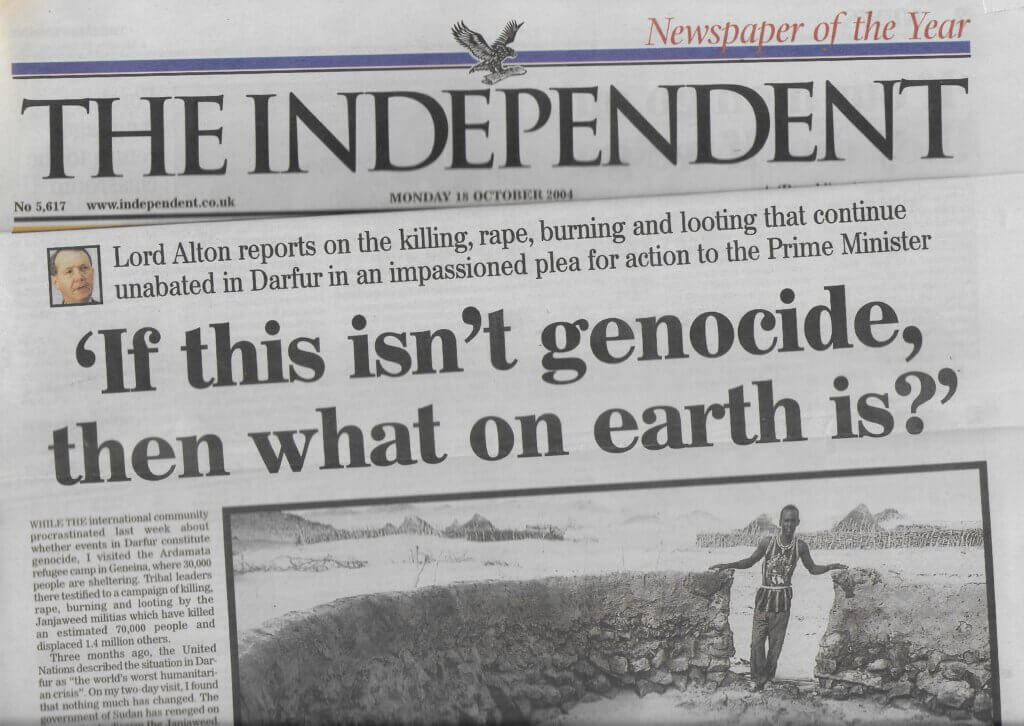

When I first raised the depredations of the Janjaweed militia, as long ago as 2001, thousands were said to be dying. By 20 May, 2004, with an estimated 30,000 dead, I asked the Government:

“What has to happen to change the passive role we have taken so far of merely monitoring the situation? Are we not in grave danger of making the same mistakes that we made at the time of the genocide in Rwanda?”.

The Government replied:

“there is now a ceasefire that has been broadly holding”.—[Hansard, 20/5/04; col. 876.]

There was never a ceasefire in Darfur and, in any event, the deliberate displacement and corralling by the Janjaweed militia of nearly 2 million defenceless people into makeshift camps will ultimately lead to death as certainly as a bullet in the head. The evidence bears me out that, while the world has been sleepwalking, Darfur has been dying.

In asking a question on 15 September last year, I referred to United Nations figures showing that the number of dead had risen from 35,000 to 50,000. On 18 October, in response to a further question, the noble Baroness, Lady Amos, said that the figure could be as high as 70,000. As recently as 23 March 2005, I drew attention to the findings of the House of Commons International Development Committee‘s devastating report on Darfur. I hope that there will be an opportunity for us to debate the implications of that report in more detail. That committee put the number of dead at a staggering 300,000. Last month, an American university concluded that the number might be as high as 400,000. Compare that with the 300,000 people who lost their life in the tsunami in south-east Asia and you have some idea of the scale of the genocide.

Yesterday, in the New York Times, a report appeared entitled “The Mournful Math of Darfur: The Dead Don’t Add Up”. It stated:

“Darfur’s dead have been tossed into the bottoms of wells, dumped into mass graves, interred in sandy cemeteries and crudely cremated. Children have been snatched from the arms of their mothers and thrown into fires, villagers dragged on the ground behind horses and camels by ropes strung around their necks.

All of which makes the important and politically charged task of counting the precise number of victims of the two-plus years of war in western Sudan a virtually impossible exercise”.

The New York Times then asks:

“Is the death toll between 60,000 and 160,000 . . . Or is it closer to the roughly 400,000 dead reported recently by the Coalition for International Justice . . .?”.

Whatever the numbers, staggering fatalities have occurred in Darfur, and we have shown remarkable impotence in facing that tragedy.

Earlier this month, on 2 May, Oxfam published a report that echoed a point that I have repeatedly made: internally displaced persons in Darfur face starvation because they have been unable to plant crops. When the rains come, access to roads and camps will be washed away. Hygiene in the camps, as I have seen first-hand, is already compromised, and the security of humanitarian workers remains an issue. I particularly welcome today the Minister’s current assessment of the position of internally displaced persons. If we do not have a clear picture and strategy for dealing with the issue, the hundreds of thousands will become millions.

The Janjaweed and the Government of Sudan have manipulated the international community, which has been guilty of prevarication and feeble posturing. The noble Lord, Lord Garden, rightly asked what thought we had given to the role of an international force, including the possible presence of the UK military, in Darfur. Before we do that, we will need to challenge the assertion of the Government of the Sudan that the stationing of a mere 100 Canadian soldiers in Darfur would be “unacceptable interference”.

Of course, I welcome the cash aid that we have given the African Union, to which the noble Lord, Lord Drayson— I also welcome him to his ministerial post—referred, and the heavy lifting equipment provided by NATO to assist them. But there are still only 2,400 African Union troops in an area the size of France. We are putting poultices on the problem rather than tackling it at its roots.

On 18 October last year, the noble Baroness, Lady Amos, told us that the African Union presence would be expanded. The UN estimated that at least 12,000 personnel were needed. The situation still has not improved. The promised enhanced African Union presence is urgently needed, and we should use our voice in the Security Council, as the noble Lord, Lord Howell intimated, to insist that Khartoum’s veto to the stationing of an international force is repudiated and the mandate strengthened. What is the point in passing mandatory Chapter 7 resolutions, as we have done, requiring the disarming of the Janjaweed, if we do not have the determination to implement them? All that that achieves is the discrediting of the UN. It also encourages a climate in which the Janjaweed militia, supported by the Government of the Sudan, believes that it can contrive to wage war against the people of Darfur with impunity.

Along with others in your Lordships’ House, I have argued that we need a no-fly zone over Darfur. My colleague, the journalist, Rebecca Tinsley, who travelled with me to Darfur last autumn, spoke to a human rights activist in Khartoum earlier this week. He had been in southern Darfur on 13 May and witnessed an attack by a government helicopter. How much proof does the world need? How many more have to die?

Two reports came to my attention earlier today, from the Darfur Centre for Human Rights and Development. One report states:

“On 11th May 2005, a group of Janjaweed militia opened fire against IDP women from Kasab camp north of Kutum town in Northern Darfur, when they went out searching for wood. In the attack one person was killed and two seriously injured”.

The other report states:

“This centre has received information that government militias attacked Labado area again yesterday, 17th May 2005, killing three civilians, wounding three others and looting 140 livestock”.

On 4 May, the UN situation representatives reported on the build-up of militia in the mountain areas, Jabra, and the feared increase in violence. They stated:

“The build-up of militias south of Thor and in Abu Jabra/Tege, in South Darfur, and especially the increased aggressive behaviour of Arab militias is disconcerting. Rumours of attacks on the Jabra continue, and fears of violence, fuelled by past incidents are keeping agencies from accessing those areas”.

I have consistently argued that those responsible for those atrocities and for what I believe to be genocide in the technical sense of that word should be brought to justice. I applaud the role that Her Majesty’s Government played in persuading the United States not to veto a referral of the perpetrators to the International Criminal Court. However, in that context, we should note two recent events. On 30 May, Musa Hilal, leader of the Janjaweed, showed his contempt for the international community and the victims of the Darfur crisis by stating in a speech that he would not be subject to any of the resolutions passed either by the UN Security Council or the UN Human Rights Commission. Speaking in Kebkabiya, northern Darfur, he said that he would not be disowned, would not agree to relinquish any weapons, and that,

“nobody will be able to try me or bring me to justice in any way”.

According to the Darfur Centre for Human Rights and Development,

“his accounts were further corroborated by the heavy presence of officials of the Sudanese government at a meeting who had accompanied him and who had facilitated his travel to the area”.

Let no one be in any doubt about the umbilical cord that ties the Janjaweed militia to the Government of Sudan.

On Wednesday, I tabled a Written Question to Her Majesty’s Government about a further development. Last weekend, human rights activists were arrested in Khartoum, and Dr Mudawi Ibrahim is now facing the death penalty. I hope that the Minister will tell us today that we will make the strongest possible protest against the taking of the life of a man who has stood up for human rights in Sudan. After all, these are Muslim people who are taking a stand for human rights, and we should stand on their side.

On 27 April last year, our ambassador to Sudan, William Patey, held a reception in Khartoum to celebrate the birthday of Her Majesty the Queen. He rejoiced that the first British trade mission was on its way; that British Airways had reinstated flights; that 130 British companies were operating in Sudan; and that trade was up 25 per cent on the previous year. Although he also rightly urged Sudan to secure peace, I find it, at best, mildly confusing that we can contrive a policy of “business as usual” with a government with so much blood on their hands. An early policy of targeted oil sanctions would have been more appropriate.

I am concerned that only today a report from the International Crisis Group in New York states that the Belarusians have sent a letter to the sanctions committee of the UN seeking permission, which the ICG believes will be granted, to sell arms to Sudan. As the noble Lord, Lord Hannay, reminded us, we have opportunities to raise the issues in effective ways, and I hope that we will take them.

On 2 February, at col. 278, I reminded the House that on 1 January the Prime Minister wrote in the Economist, that,

“Darfur remains a catastrophe, and we cannot turn . . . away from it”.

In the gracious Speech, the Government said that they would contrive to push for a resolution of the conflict in Darfur. I welcome that, and I hope that in all parts of the House we will get behind that objective. For the terrorised, suffering people of Darfur, that cannot happen a day too soon.