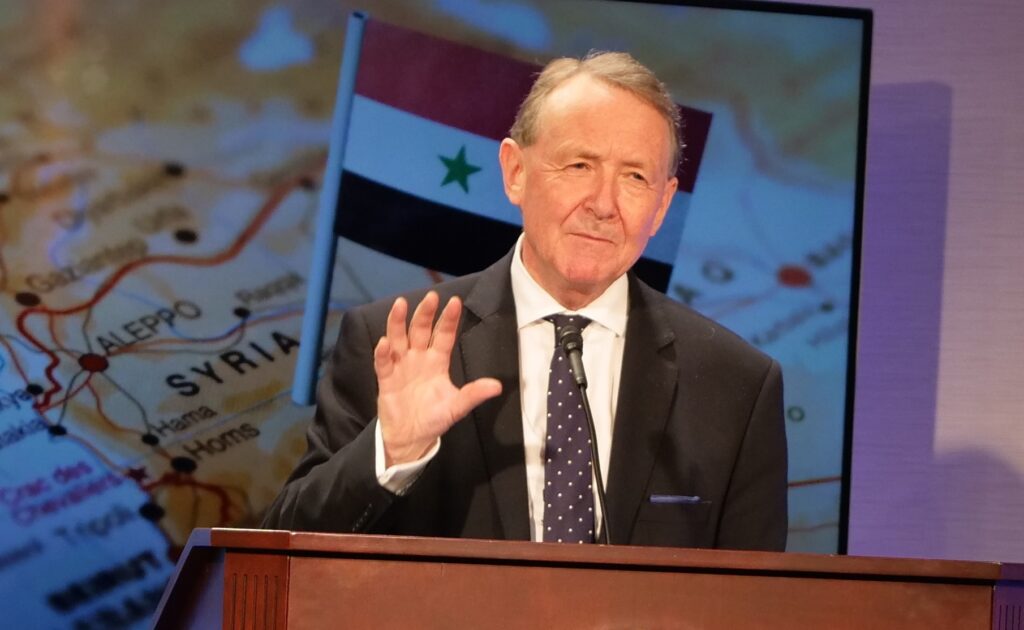

Lord Alton of Liverpool and the Coalition for Genocide Response would like to invite you to a webinar:

“The Question of Mass Atrocity Monitoring and Determination”

17 November 2020 at 5 PM (GMT)

Zoom Webinar (Side event to the Ministerial on FoRB in Warsaw)

There are two states which currently stand accused of playing a role in genocide against religious minority groups; Myanmar, where the military stands accused of perpetrating genocide against the Rohingya Muslims and China whose government is allegedly perpetrating genocide against the Uighur Muslims. In both cases, the allegations are disputed by their respective governments and it is correct to say that the allegations are yet to be proven. Such a (final) legal determination needs to be made by an independent tribunal. This may take years. Yet, in the meantime, the nature of the atrocities roam the grey space as states do little to make their interim determinations of genocide to inform their responses.

The question is then how do states fulfil their duties under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, to prevent and suppress genocide and punish the perpetrators. Specifically, how do states fulfil their duty to prevent that, according to the International Court of Justice, should be triggered ‘at the instant that the State learns of, or should normally have learned of, the existence of a serious risk that genocide will be committed.’

The speakers will engage with the question of mass atrocities monitoring and determination as a prerequisite to fulfilling their duty to prevent such atrocities as genocide.

Remarks by David Alton at a side even at the international Ministerial on Religious Freedom being held in Poland: “Breaking the Vicious Circle of Genocide.”

It is frightening to think that in the last 5 years alone, we may have witnessed four cases of genocide. However, even more, frightening is, that despite the promises made to prevent such atrocities in the future, the responses are always too late and not enough.

The question is why?

Is it because of the lack of political will? Maybe.

However, there is more to it than that and as I hope to explain, it is because we do not have the basic mechanisms that would help us to trigger the duties laid upon us by the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the Genocide Convention).

The Genocide Convention does not require states to introduce such mechanisms, but without such mechanisms the duties under the Genocide Convention are often not worth the paper on which they are written.

As the International Court of Justice confirmed ‘a State’s obligation to prevent, and the corresponding duty to act, arise at the instant that the State learns of, or should normally have learned of, the existence of a serious risk that genocide will be committed. From that moment onwards, if the State has available to it means likely to have a deterrent effect on those suspected of preparing genocide, or reasonably suspected of harbouring specific intent (dolus specialis), it is under a duty to make such use of these means as the circumstances permit.’

What does it mean that the ‘state learns of, or should normally have learned of’?

It means that the state should be engaging in monitoring and analysing early warning signs – harbingers – the canaries in the mine – to be able to determine whether the early warning signs are suggestive of mass atrocities to come.

Is it enough to just monitor such early warning signs without making the determination of genocide? No.

As the International Court of Justice asserts, once the state learns of the risk of genocide, the state is obliged to act.

Hence, we need three main things: monitoring, determination, and action.

The monitoring should be followed by a determination and the determination should be followed by action.

These three are interlinked and interrelated.

Monitoring without determination means that action will not follow. Determination and action without monitoring pose the risk of the action being misinformed.

Monitoring followed by action, but without determination, may not be able to respond to atrocities adequately or at all.

The question is then, what is the UK Government doing to address mass atrocities. It claims to have comprehensive mechanisms in place. Even if this is the case, such mechanisms would most likely fall within the scope of monitoring, but not determining and not acting.

Indeed, over many years, – even in a parliamentary reply which I have received today and posted on my web site – the UK Government’s response to the question of genocide determination has been the same: that it is for the international judicial systems. This even though such international judicial systems are either inadequate, non-existent, or compromised by Security Council vetoes.

It has to be emphasised that, as it stands, the UK Government simply does not have any formal mechanism that allows for the consideration and recognition of mass atrocities that meet the threshold of genocide, as defined in Article II of the Genocide Convention. The Emperor has no clothes.

As a result, the Government is at a major disadvantage when trying to fulfil its Convention duties to protect, prevent and punish. In 2017, this lack of a formal mechanism, whether grounded in law or policy, was criticised by the Foreign Affairs Select Committee report on the situation in Rakhine. The report stated:

“We are seriously concerned to find that the FCO has not undertaken its own analysis of the situation, nor committed its own expert team to gather evidence. The Minister said that its effort was focused on addressing the humanitarian situation, but it is unclear why humanitarian support and legal analysis cannot go hand-in-hand”.

Like a broken record the UK Government will then endlessly repeat that genocide determination is not crucial but that actions to address mass atrocities are. However, the question is then, how can we address mass atrocities without fully understanding their nature.

Its reliance on international judicial systems is flawed because parties to the genocide convention are the duty bearers under the genocide convention, not the international judicial systems.

Parties to the genocide convention, such as the United Kingdom, must act to ensure that the determination is made by a competent body in accordance with the law and policy in the state and decisive steps follow that fulfil the state’s obligations under the genocide convention to prevent and punish.

Furthermore, in the case of the Daesh atrocities in Syria and Iraq – which I visited a few months ago – and the Burmese military atrocities in Burma – which I have also seen first-hand in the Karen State – , there are no international judicial systems that can make the determination of genocide without the agreement of countries often complicit in the genocide or allies of that country. Think of China and its veto in the Security Council, but there are others too.

Establishing such mechanisms would take years and even more years before a formal determination of genocide is actually made. And the cynic in me knows that this often suits some officials in Whitehall who would rather sit on their hands.

Over the recent years, because of these failures in the way in which the Government has failed to address such mass atrocities as genocide, I have been working on several legislative initiatives to address the situation.

Among others, my proposed Genocide Determination Bill would invest the High Court of England and Wales—not politicians or officials —with the power to make a preliminary finding on cases of alleged genocide and subsequently refer such findings to the International Criminal Court or a special tribunal.

The proposal responds to the argument of the Government that the determination of genocide should be made by a competent court—the competent court here is the High Court, not an international court—and recognises that under the genocide convention it is the duty of the state, not international institutions, to act.

Most recently, I tabled an amendment to the Trade Bill mirroring the Genocide Determination Bill and proposing a mechanism for the interim determination to prevent Her Majesty’s Government to become complicit in such atrocities by doing business with states standing accused of genocide. It will come back to the floor of the House next month.

Currently, the most obvious global contenders for predetermination are China and Myanmar for their crimes against Uighur and Rohingya Muslims.

However, if state collaboration in countries such as Syria and Iraq against ethnic or religious minorities, such as the Yazidis, were proven, they too could fall within the terms of the amendment. Nevertheless, we should be clear: the threshold is exacting, and the amendment will not stop any trade with any country until the High Court has made a preliminary determination that there is a prima facie case of genocide, with the Government able to deploy a contradictor in the court.

As a signatory to the convention, we are required to prevent genocide, to protect those affected by genocide and to punish those responsible. However, if no judicial authority declares a genocide to be underway, we are not obliged to act—hence the vicious circle.

We need to do better. But this will not happen if we continue to ignore the elephant in the room – the lack of a mechanism to move from reports of genocide to doing something about it.

Prevention of such atrocities as genocide is not a matter of a chance. We need to monitor the early warning signs – I think of Nigeria and Mozambique – analyse then and make the interim determinations reflective of the nature of the atrocities, and then act. I will never forget my visits to Iraq, Darfur, Rwanda, South Sudan, North Korea, Burma Tibet and Western China – and what I saw and heard in those places should remind us all how quickly and how easily the words “never again” can sound like hollow rhetoric and a meaningless empty slogan.

2019 ministerial with Ambassador Sam Brownback and former Congressman Frank Wolf