Gladys Aylward, the little woman, and China’s Inn of The Sixth Happiness – or, more accurately, the Inn of the Eight Happinesses

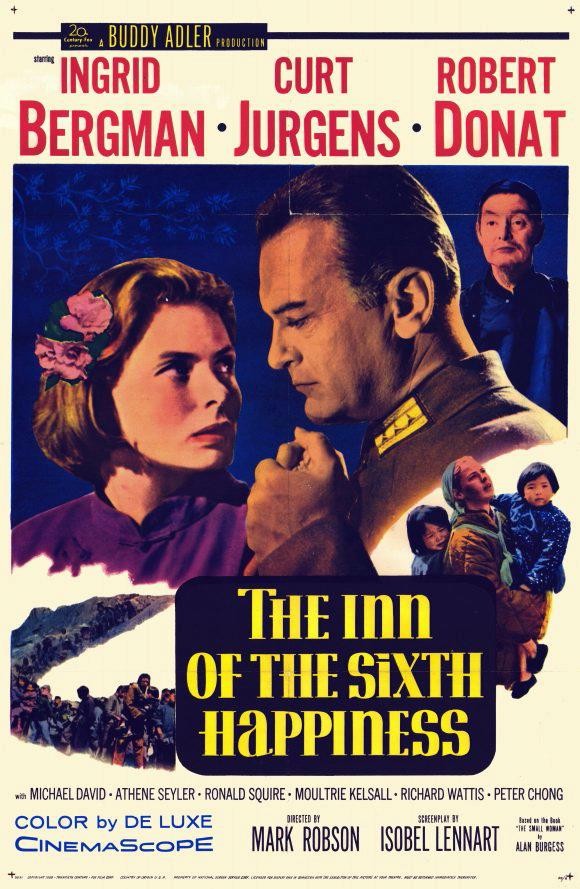

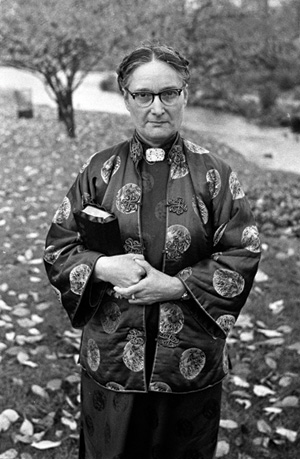

There is a lovely movie, staring Ingrid Bergman, called “The Inn of the Sixth Happiness.” Made in 1958 it celebrates the remarkable life of a petite woman, born in 1902 in Edwardian England, called Gladys Aylward. It’s a charming film but on recently reading a biography of Miss Aylward I realised that the Hollywood make-over does not do justice to, and sometimes distorts, the real story of this brave and determined Christian missionary.

For one thing, the casting of a tall Swede is entirely at variance with the small woman from Edmonton who spoke with a broad cockney accent. But the movie also takes any number of liberties with the story itself. Once she tells them of her plans to go to China we entirely lose the tensions that erupt between Gladys Aylward and her family and the film then invents an effortless introduction between a Gladys’ employer and an old friend in China. Perhaps most tellingly of all, in addition to changes made to any number of characters and places the movie revolves around the Inn of the Sixth Happiness while the actual setting was the Inn of Eight Happinesses – taking its name from a Chinese numeral thought to be auspicious.

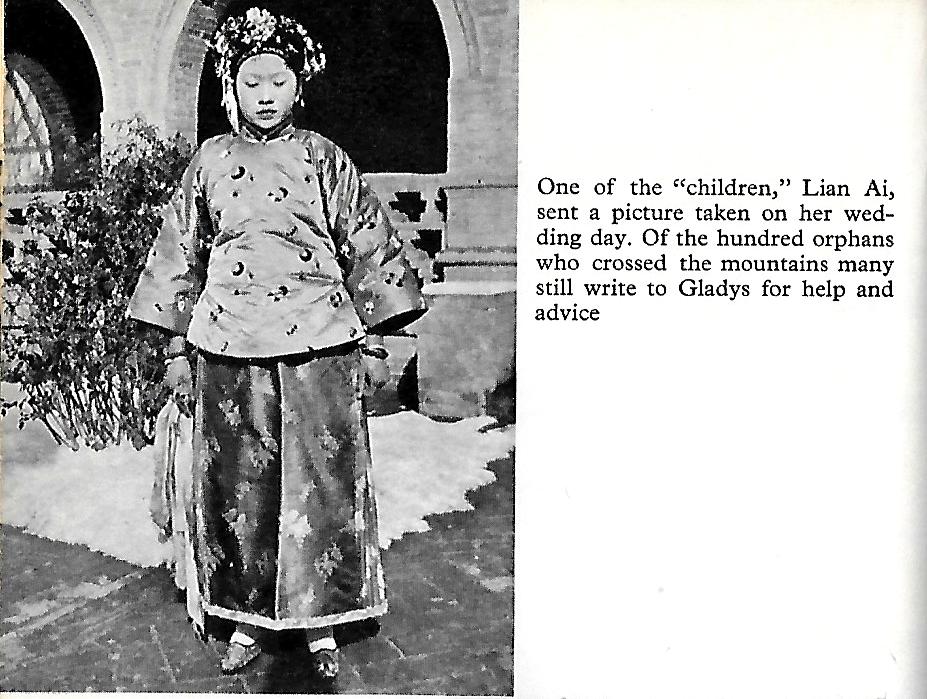

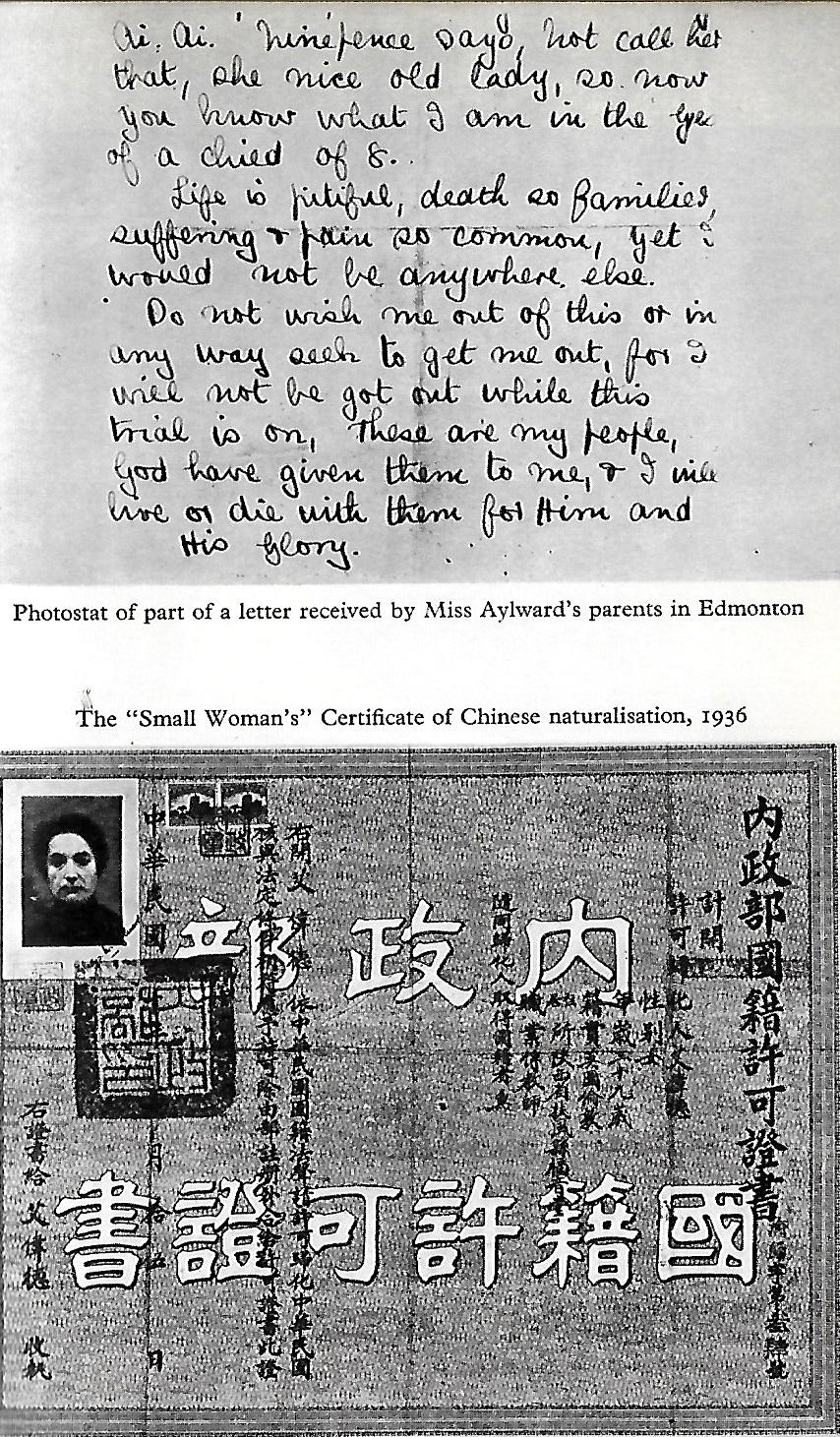

When the film first appeared Gladys Aylward was upset by the portrayal of Colonel Linnan – a brave Chinese soldier who was wrongly presented as half European – and distressed by an invented Hollywood love scene and the suggestion that she had left her work with her orphans to be happily reunited with the Colonel. For a woman who had decided early on to give her entire life to God, and who had never even kissed a man, she believed her reputation to have been sullied. Her work with orphans also continued until 1970, when she died, having by then founded the Gladys Aylward orphanage in Taiwan.

The real story of Gladys Aylward is one which deserves to be told with all its hard edges and without taking liberties with its powerful narrative.

Here is a working class parlour maid who dreams of becoming an actress but instead reads an article about China and about the millions of Chinese people who had never heard about Christianity. Having felt God’s call to go to China Gladys is rebuffed by her family, friends and church. The missionary society told her that her “qualifications were too slight, my education too limited, and the language far too difficult to learn.”

Meanwhile, she goes to work in a house where two old retired missionaries live and at last she receives some encouragement. They tell her to “keep on watching and praying.” She does, and begins saving to pay the £47-10p single train fare from London to Tientsin in China. To go by ship would have cost twice as much.

Small unexpected things now began to happen to Gladys.

Her savings multiplied, giving her the fare in months instead of the anticipated three years. In 1932, completely alone, she began a perilous journey across Russia and Siberia, into war zones occupied by the Japanese. Near the Manchurian border she was made to leave the train and nearly froze to death and she admitted that “for the first time real doubts came to mind.” She felt God telling her not to be afraid and that He was with her.

She was forced to walk back along the railway track to a junction and, later, some Russians tried to abduct her. She also saw fifty people, many of them girls, in chains being taken to Siberia to Stalin’s camps – “from that moment I hated Communism with all my being:” – hated Communism but loved the people who lived in the lands in which the ideology came to dominate.

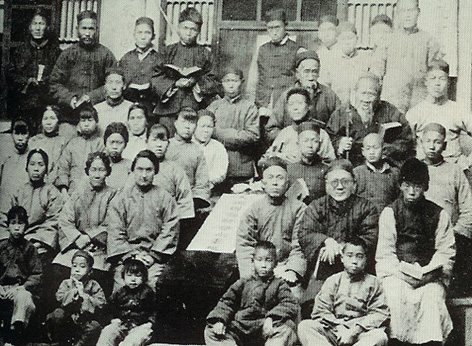

After further tribulations Gladys Aylward eventually made it to Tientsin where she went to work with a Scot, Jeannie Lawson, who was trying to turn a dilapidated building into an inn where muleteers would stay overnight and where, with good food and hospitality, they could hear stories from the Bible as they ate. This was how Gladys Aylward came to quickly become fluent in the Chinese language.

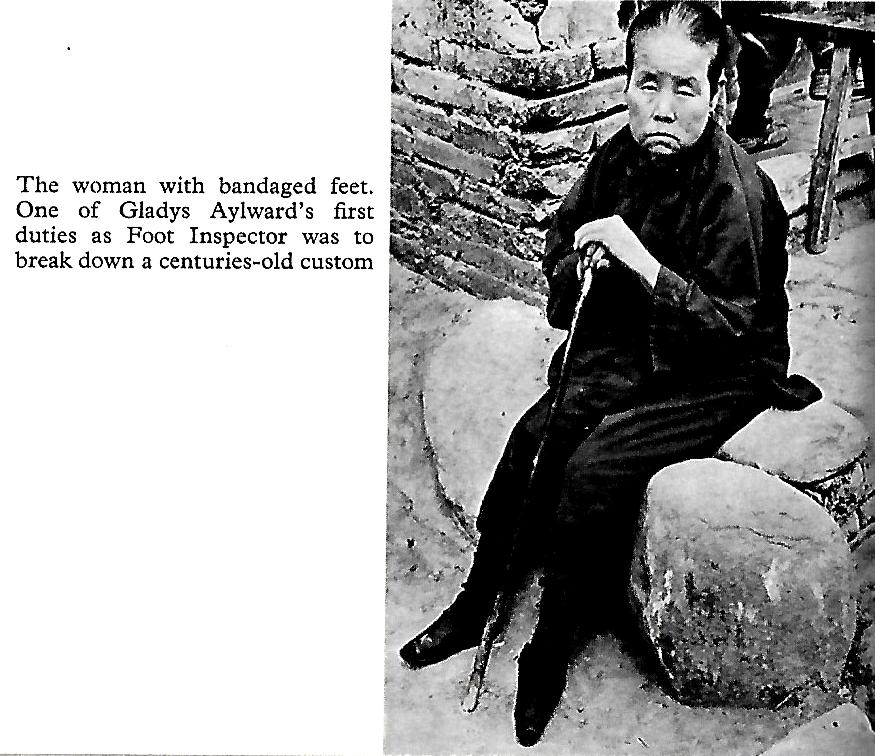

After Lawson’s death she continued with the inn but she was also asked by the Government’s senior regional official, the Mandarin, to work with him. He gave her the task of helping him to outlaw the traditional foot-binding of Chinese girls.

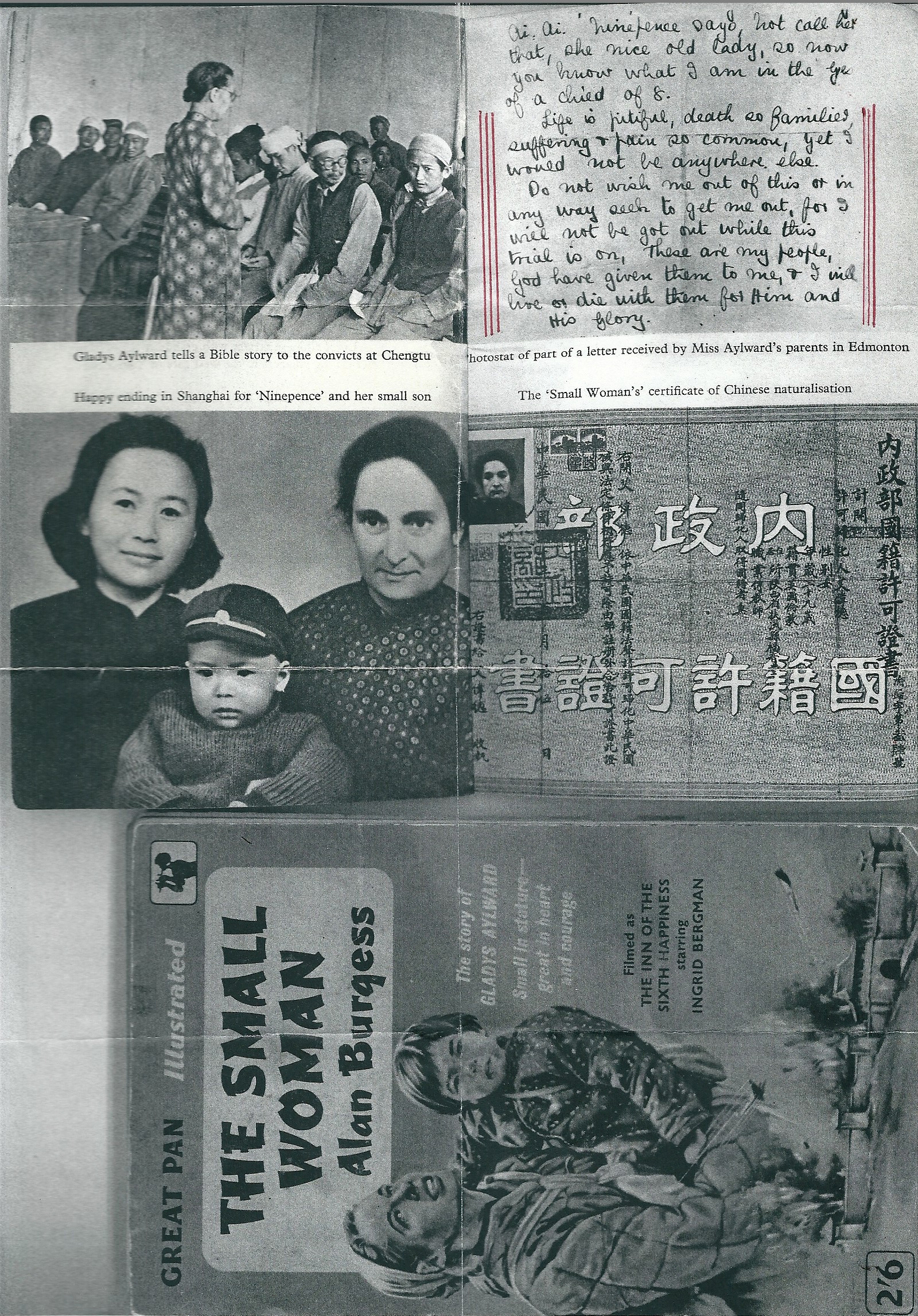

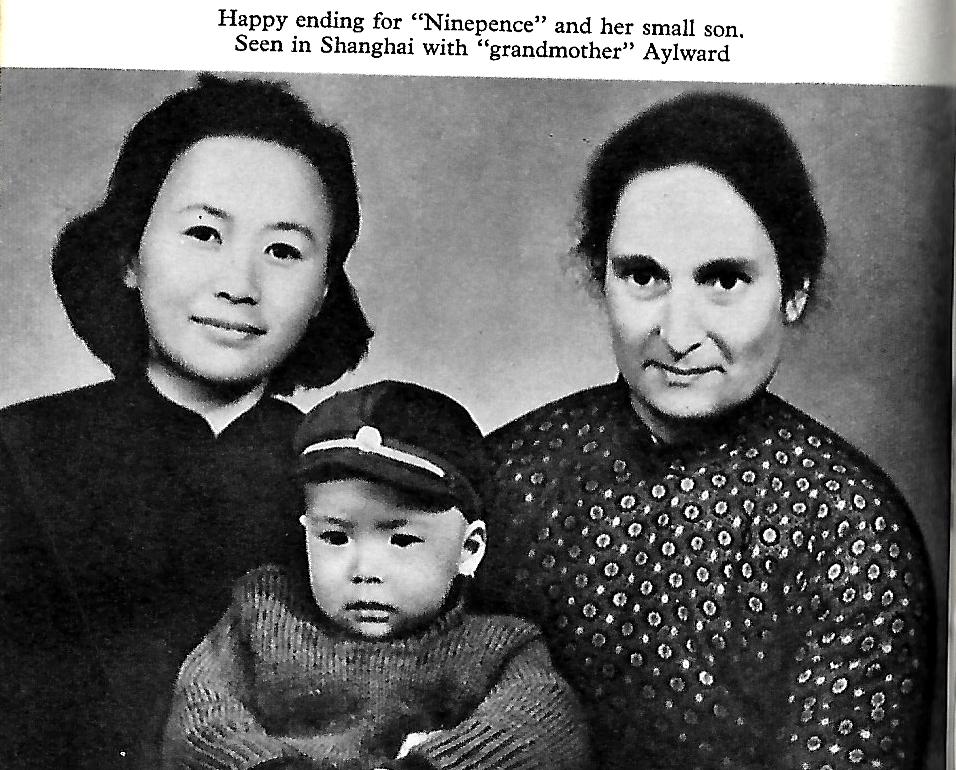

Men thought tiny feet were attractive but women’s foot-binding often led to deformities and crippling disabilities. Gladys Aylward helped the Mandarin to end the practice in their province and as she travelled from village to village she evangelised the people she met. An encounter on the side of a road also led her to start rescuing children who were being abandoned or sold. To save the life of one little girl she gave all the money she had: “So Ninepence came into my life and helped to fill the aching void.”

A few months later Ninepence brought in a little boy from the street and the orphans multiplied.

Later, Gladys Aylward became involved in prison reform – and her biography records stories of extraordinary conversions – from hardened criminals to a prison governor, a rebel leader, and even the Mandarin himself. Her encounter with a remote monastery of Buddhist lamas – who told her that they had been waiting for her – is particularly touching.

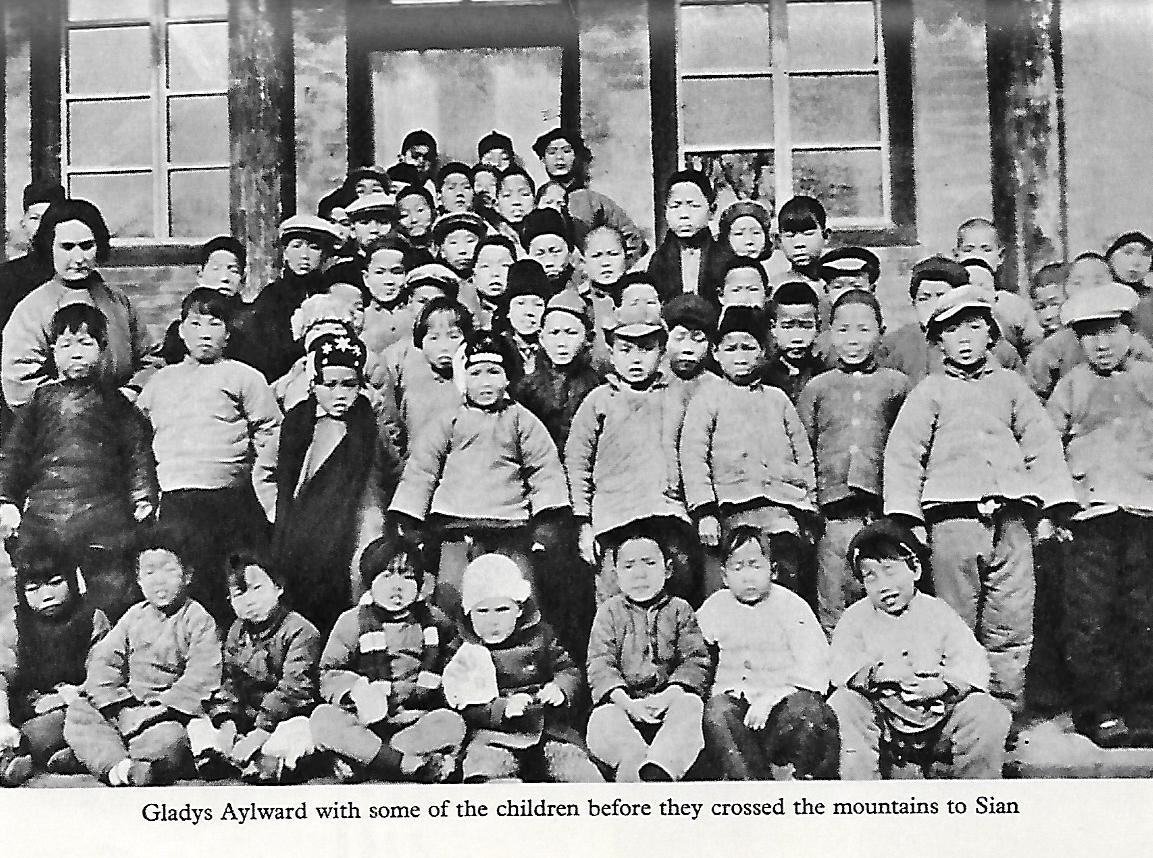

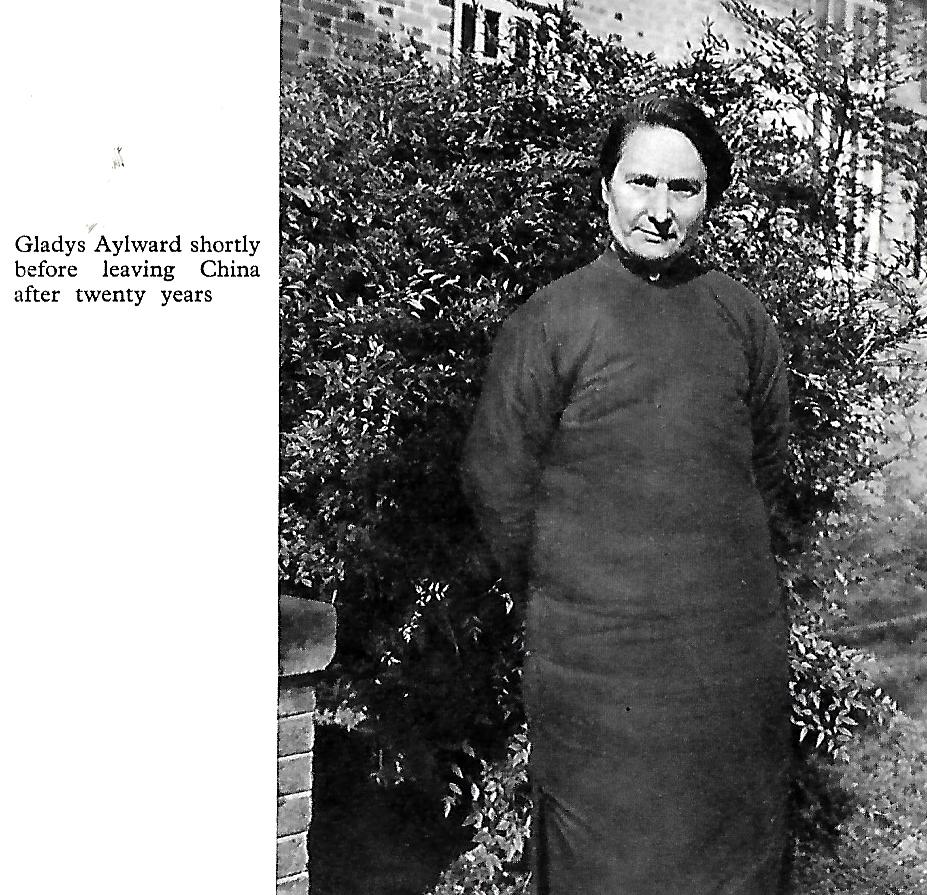

In 1936 she was given Chinese citizenship and became officially known as A-weh-deh – meaning “virtuous one.” Two years later the Japanese invaded and they put a price on her head. She was wounded in the fighting but led over 100 orphans on a perilous journey over the mountains to safety. Suffering a complete collapse of her health she was diagnosed with relapsing fever, typhus, pneumonia, malnutrition and utter exhaustion. For over a month she was barely conscious.

She would later write that “My heart is full of praise that one so insignificant, uneducated and ordinary in every way could be used to His glory and for the blessing of His people in poor persecuted China.”

That Christianity has become so influential in today’s China is in no small measure a result of the powerful witness and dedicated work of men and women like Gladys Aylward. But her story also underlines the truth of the Psalmist’s prediction that “the stone which the builder has rejected has become the corner stone.”

Also see:

https://onthemountainswordpress.wordpress.com/2018/08/04/the-journey-begins/

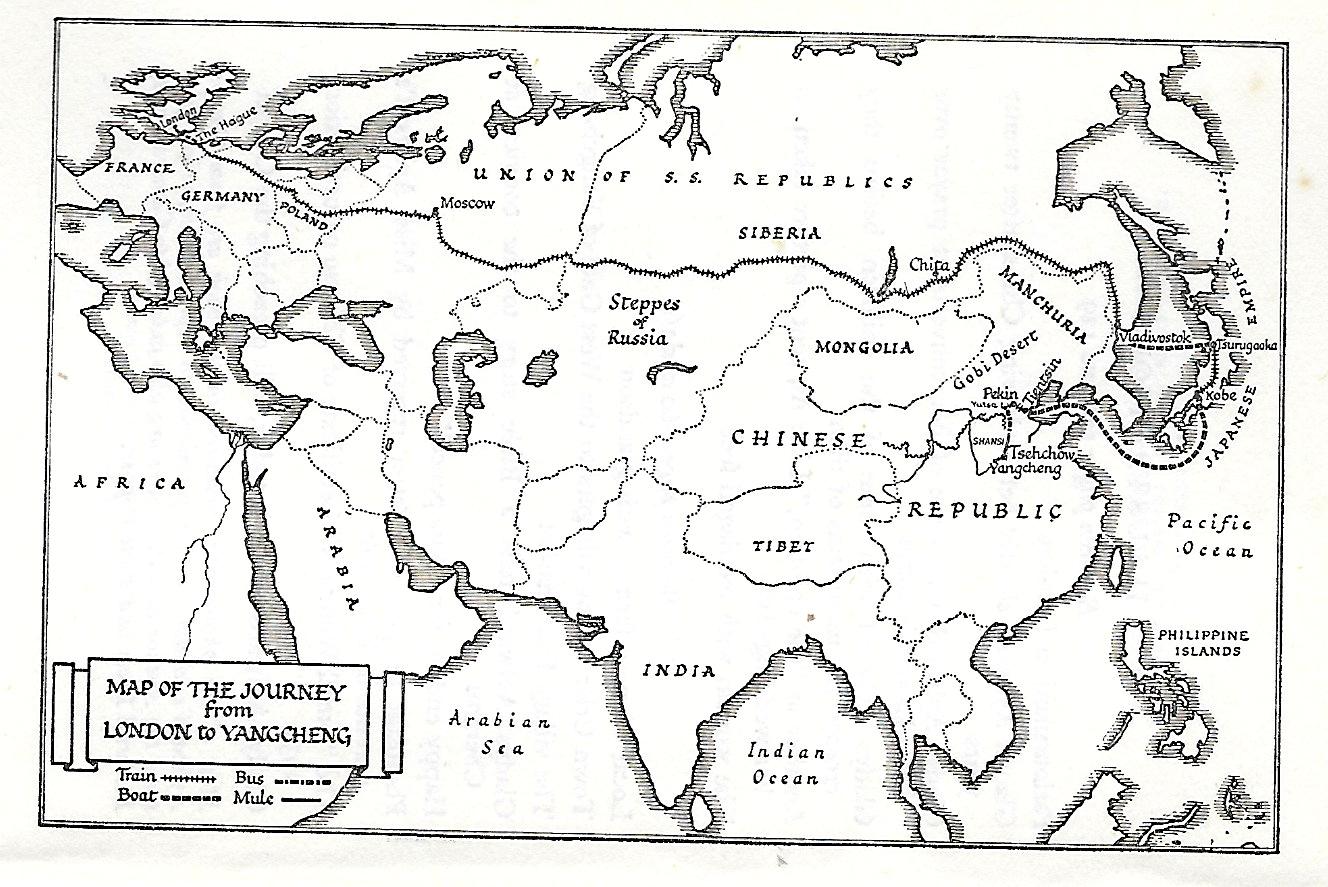

From London to Yangcheng

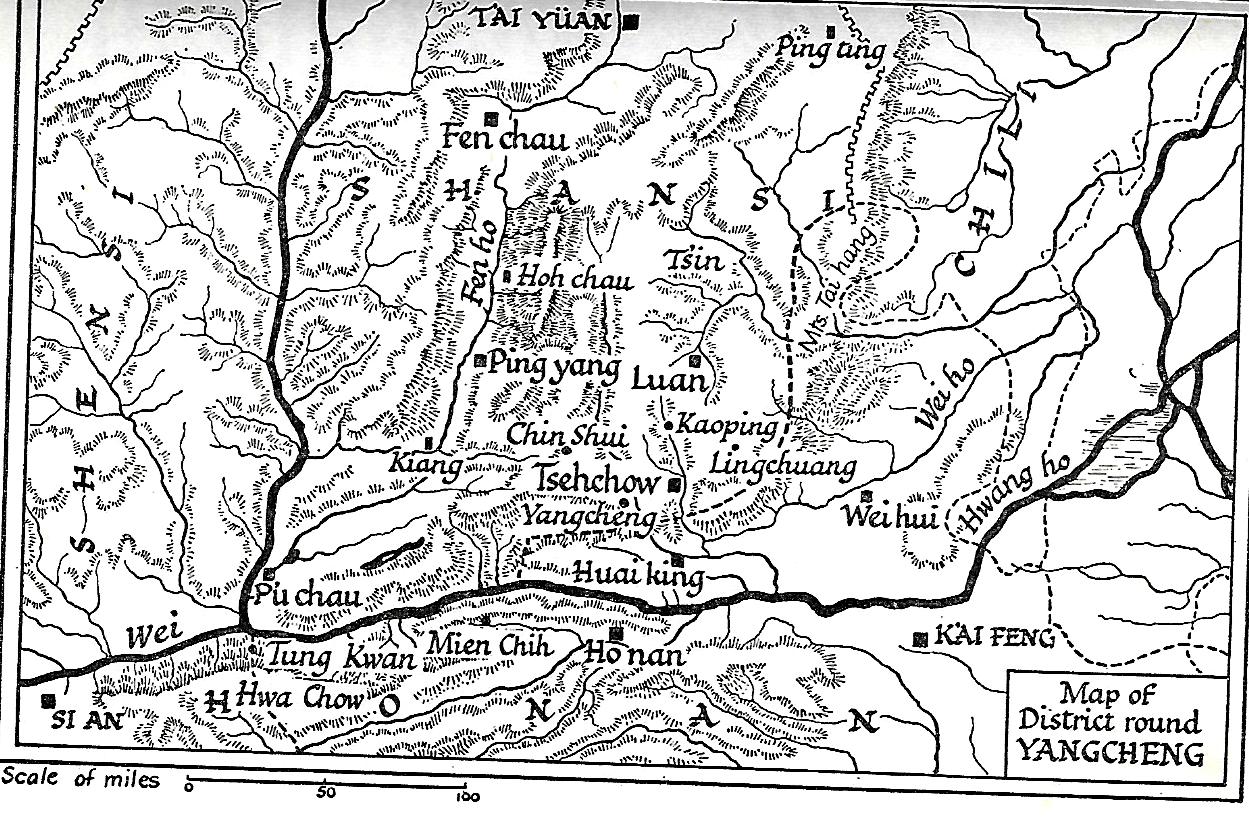

The District around Yangcheng

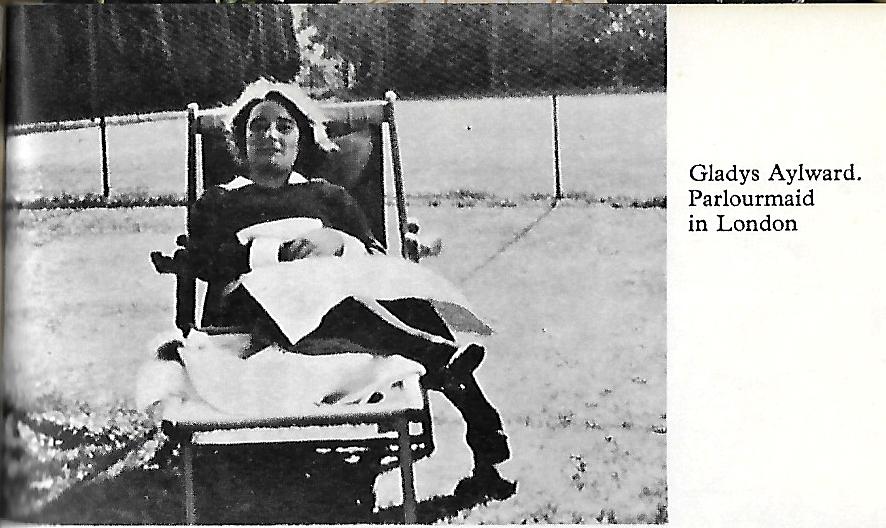

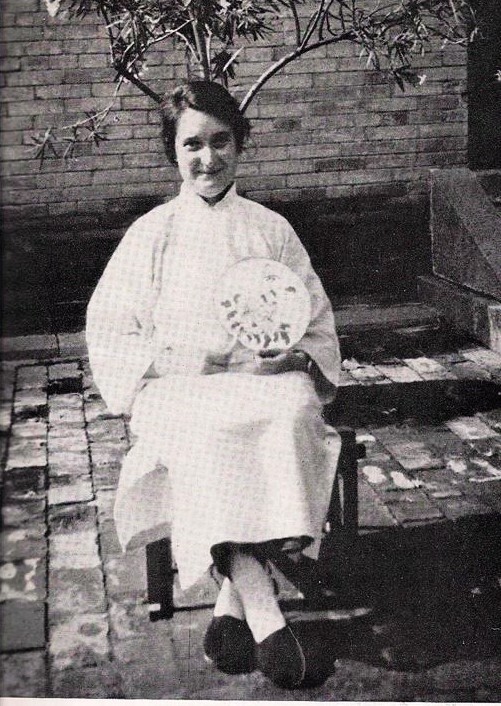

Gladys Aylward as a parlourmaid before leaving London

The Yangcheng fruit market

Th

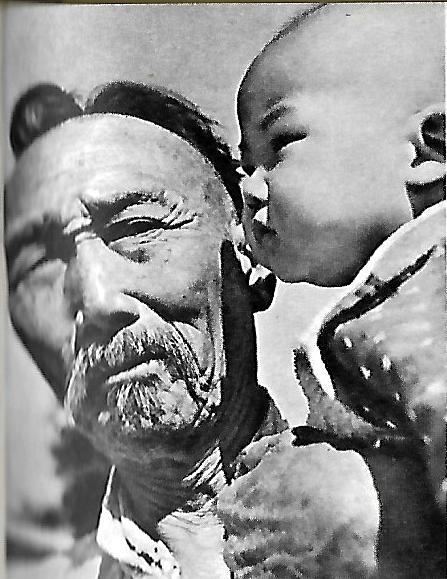

A Yangcheng farmer and his grandson

A woman with bandaged feet. Gladys Aylward became the Mandarin’s Foot Inspector appointed to end this practice.

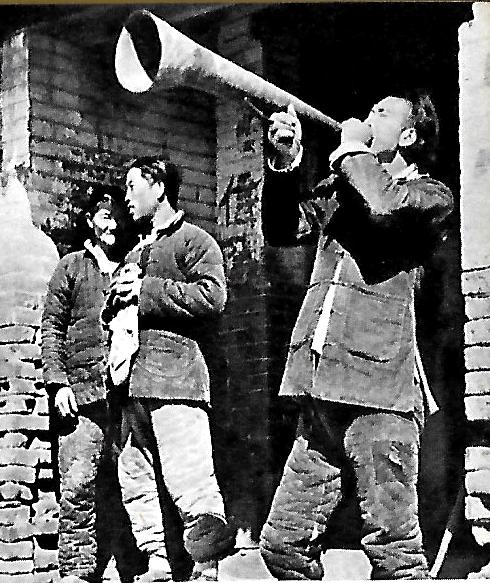

The town crier calling villagers to the West Gate of Yangcheng

Telling a Bible story to convicts at Chengtu

Telling a Bible story to convicts at Chengtu

Preaching the Gospel with the same Bible she took everywhere on her travels

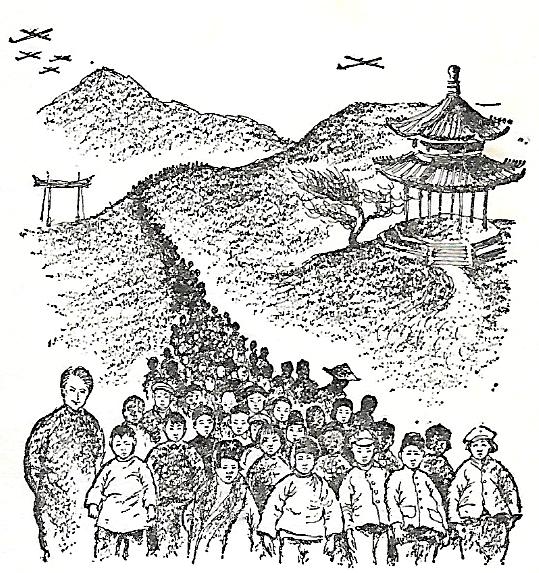

Crossing the mountains of Sian to escape Japanese soldiers and aerial bombardment

The final pages of Alan Burgess’ biography of Gladys Aylward, The Small Woman, published in 1957.

.

.

Liverpool Chinese Gospel Mission

When the film “The Inn of the Sixth Happiness” was being made in North Wales, a lot of the children used in the film Were from Liverpool. Gladys Aylward, whose life the film was about, set up a Chinese Gospel Mission at 20 Nelson Street Liverpool.

20 Nelson Street, Liverpool: Early 19th century brick house in China Town, Liverpool. Chinese Republican Progress Club which opened in 1941 and some time between 1948 and 1958 a mission founded by Gladys Aylward. Currently a restaurant.

Liverpool and the Movie (BBC report)

In 1958, children from Liverpool’s Chinese community were used as extras in the Inn of the Sixth Happiness, which starred Ingrid Bergman.

Snowdonia doubled as China in the film about missionary Gladys Aylward.

|

Perry Lee, former child extra

|

The film was based on the true story of how she led a group of orphans to safety across the mountains in war-torn China.

The film is being featured as part of the new film trail which is being organised by the Wales Screen Commission.

A commemorative plaque will be unveiled by the actor Burt Kwouk who played the part of the Chinese schoolteacher Li who sacrificed his life to save the children.

One of those children was Perry Lee who is now a 51-year-old housing manager.

He said: “It was amazing, it was really great and I have extremely fond memories of the experience.

|

In the summer of 1958 Snowdonia doubled as worn-torn China

|

“Once they had decided to film in Snowdonia, the Chinese community in Liverpool was the obvious place to come to find the children to play the parts of the orphans.

“I was just turned six and my brother William was four and a half.

“We got paid £12.50 a week which was a lot of money in those days so I got a bike out of it and he got a little scooter.

“For a six year old it was tremendously exciting but it wasn’t all glamour.

“We weren’t allowed to wear shoes. If you were lucky you were allowed to wear pumps and if you were very unlucky you had to have rags tied around your feet – painted red to simulate blood.

“And we had to dive in the cow pats whenever the Japanese planes came over.

“You were never conscious of the cameras being trained on you but my big scene was the river crossing when Ingrid Bergman grabbed me.”

Actor Mr Kwouk is perhaps better known these days as the manservant of Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther films but Inn of the Sixth Happiness was the one that launched his movie career.

He said: “They were a lively bunch but very well behaved, they had chaperones and they were very well taken care of.”

Wikipedia

Gladys May Aylward (24 February 1902 – 1 January 1970) was a British-born evangelical Christian missionary to China, whose story was told in the book The Small Woman, by Alan Burgess, published in 1957, and made into the film The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, starring Ingrid Bergman, in 1958. The film was produced by Twentieth Century Fox, and filmed entirely in North Wales and England.

Early life

Gladys Aylward was born to a working-class family in Edmonton, North London, in 1902. Her parents were Thomas John Aylward and Rosina Florence Aylward (née Whiskin). Her siblings were Laurence and Violet.

She worked as a domestic worker (housemaid) in a posh house from her early teens. She always asked herself why she was short and had black eyes and hair instead of blond hair and blue eyes like the people she worked for. She later felt a calling to go overseas as a Christian missionary. She was accepted by the China Inland Mission to study a preliminary three-month course for aspiring missionaries, but was not offered further training due to lack of progress in learning the Chinese language.

On 15 October 1932, having worked for Sir Francis Younghusband, she spent her life savings on a train passage to Yangcheng, Shanxi Province, China. The perilous trip took her across Siberia with the Trans-Siberian Railway. She was detained by the Russians, but managed to evade them with local help and took a lift from a Japanese ship. She travelled across Japan with the help of the British Consul and took another ship to China.

Work in China

On her arrival in Yangcheng, Aylward worked with an older missionary, Jeannie Lawson, to found The Inn of the Eight Happinesses, (八福客栈 bāfú kèzhàn in Chinese) the name based on the eight virtues: Love, Virtue, Gentleness, Tolerance, Loyalty, Truth, Beauty and Devotion.

There, she and Mrs. Lawson not only provided hospitality for travellers, but would also share stories about Jesus, in hopes of sharing the Christian religion. For a time she served as an assistant to the Government of the Republic of China as a “foot inspector” by touring the countryside to enforce the new law against footbinding young Chinese girls. She met with much success in a field that had produced much resistance, including sometimes violence against the inspectors.[4]

Aylward became a national of the Republic of China in 1936 and was a revered figure among the people, taking in orphans and adopting several herself, intervening in a volatile prison riot and advocating prison reform, risking her life many times to help those in need.[7] In 1938, the region was invaded by Japanese forces and Aylward led more than 100 orphans to safety over the mountains, despite being wounded herself. She not only led the orphans to safety, but personally cared for them and converted many of them to Christianity. She never married, but spent her entire life devoting herself to Christian work with the people of China.

She was repatriated to Britain at the beginning of the Second World War, and taught young children at Basingstoke Preparatory School for several years. After about 10 years she sought to return to China, and after rejection by the Communist government and a stay in British administered Hong Kong, finally settled in Taiwan in 1958. There, she founded the Gladys Aylward Orphanage, where she worked until her death in 1970.

The Inn of the Sixth Happiness

A film based on her life, The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, was released in 1958. It drew from the book The Small Woman, by Alan Burgess. Although she found herself a figure of international interest due to the popularity of the film, and television and media interviews, Aylward was mortified by her depiction in the film and the liberties it took. The tall (1.75m/5′ 9″), blonde Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman was inconsistent with Aylward’s small stature, dark hair and North London accent. The struggles of Aylward and her family to effect her initial trip to China were disregarded in favour of a movie plot device of an employer “condescending to write to ‘his old friend’ Jeannie Lawson.” Also, Aylward’s dangerous, complicated travels across Russia, China and Japan were reduced to, “a few rude soldiers”, after which, “Hollywood’s train delivered her neatly to Tsientsin.” Many characters and place names were changed, even when these names had significant meaning, such as those of her adopted children and the name of the inn, named instead for the Chinese belief in the number 8 as being auspicious. For example, in real life she was given the Chinese name 艾偉德 (Ài Wěi Dé- a Chinese approximation to ‘Aylward’ – meaning ‘Virtuous One’), however in the film she was given the name 真爱 Jen-Ai,( pronounced- Zhen-Ai, meaning “true love”).[11] Colonel Linnan was portrayed as half-European, a change which she found insulting to his real Chinese lineage, and she felt her reputation was damaged by the Hollywood-embellished love scenes in the film. Not only had she never kissed a man, but the film’s ending portrayed her character leaving the orphans to re-join the colonel elsewhere, even though in reality she did not retire from working with orphans until she was 60 years old.

Death and legacy

Aylward died on 3 January 1970, just short of her 68th birthday, and is buried in a small cemetery on the campus of Christ’s College in Guandu, New Taipei, Taiwan. She was known to the Chinese as 艾偉德 (Ài Wěi Dé- a Chinese approximation to ‘Aylward’ – meaning ‘Virtuous One’).

A London secondary school, formerly known as “Weir Hall and Huxley”, was renamed the Gladys Aylward School shortly after her death.

There is a blue commemorative plaque on the house where Gladys lived near the school in Cheddington Road, London N18.

Numerous books, short stories and films have been developed about the life and work of Gladys Aylward

During the period that Gladys Aylward was in China, my mother’s cousin, Fr.Patrick Malone – an American-Irish missionary – worked in Meixien (formerly Kaying), China, where he went in 1926.

Click here: These are some of his photographs:

Fr Patrick F Malone

Missionary – Film maker – Poet

Patrick F. Malone was born in Arderry, Aughagower, Mayo. At the age of twenty he emigrated to America and was drafted in to the U.S. Army during the first World War.

He resumed his studies in Maryknoll Seminary in New York in 1918. He was ordained in 1925 after which he worked as a missionary in China for over twenty years.

He narrowly escaped death on a number of occasions and on one such occasion he had to dress up as an old woman to get past the soldiers.

He returned to Ireland in 1947 and it was then that his talent as an amateur film – maker, became recognised. Some of his films included:

The Tear and Smile of China, The Life of Our Lord (filmed in the Holy Land) Lovely Ireland His films were shown in Killawalla during the 1960s. He was related to the Malone/Gavin household and often visited them there.

Fr. Patrick F. Malone was also well recognised for his talent as a poet. Some of his work was published in magazines, newspapers and journals.

He lived at Rosbeg in Westport for many years and also at Clonbur where he died of a heart attack on the 26th of March 1979, aged 84 years.

His remains were buried in Aughagower Cemetery inside the ruined walls of the old Church.

One of his poems: Friends you used to know

When trees are sighing outside, and leaves come down to find A cover in some corner from the cold November wind When you’re sitting by the fireside and musing in the glow Ah – remember, don’t forget them – the friends you used to know.

It is again November and souls are waiting there Yes, waiting for your coming with a needy little prayer And you promised – Yes you promised In the country and the town That you would at least remember when the leaves are coming down.

It may have been some dear one who since has left our mind Or one who thought a lot of you, for you too, were so kind Ah yes, now maybe someone – someone for whom you’d care When meeting, say on Saturday, or the Market day or Fair

You loved them in their lifetime, poor Tom and Kate and May How much you said you missed them, when God took them away But now it is November, and they’re wondering are you there Wondering if you’re coming with that promised little prayer.

Do come to them, acushla, they’re our own – a pity, and I wish I’d time to tell you how they need a helping hand And now I must be going – but again, before I go Ah Hail Marys for a friend you used to know.

Fr.Patrick Malone