What did Pope John Paul I, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Edith Cavell, Dag Hammarskjold, Jose Rizal, and the fictional Maggie Tulliver all have in common? Put another way, if you were marooned on Roy Plomley’s mythical desert island, and told that you could take The Bible and Shakespeare as companions, what one other book might you choose?

The answer and common denominator to both these questions is “The Imitation of Christ” written in the fifteenth century by Thomas a Kempis, who died in 1471. It is the most widely read devotional book after the Bible. There are over 2000 counted editions – over 1000 of which are preserved in the British Museum.

Although, surprisingly, Thomas a Kempis has never made Blessed, canonised, or declared a Doctor of the Church, he has had an amazing impact on the lives of singular and diverse men and women. Many have found inspiration and consolation in the writings of this self effacing German monk. The stories speak for themselves.

Jose Rizal was the Filipino polymath and national hero, who, in 1896, aged 35, while awaiting execution by Spanish soldiers, read the book before his execution at Intramuros prison in Manila.

In 1945, Dietrich Bonhoeffer had the book in his cell the night before the Nazis led him, naked, into the execution yard where he was hanged with thin wire by strangulation.

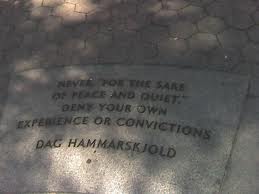

It was the only book found in the case of Dag Hammarskjold, the Swedish diplomat who became Secretary General of the United Nations and died, in 1961, when his Douglas DC-6 crashed in Zambia.

Hammarskjold famously said that “In our age, the road to holiness necessarily passes through the world of action…. He who wills adventure will experience it—according to the measure of his courage. He who wills sacrifice will be sacrificed—according to the measure of his purity of heart.”

One hundred years earlier, Mary Ann Evans, writing under the male pseudonym, George Eliot, published her “Mill on the Floss”. Maggie Tulliver is the principal protagonist. In her loneliness, the fictional Maggie Tulliver, receives no consolation from Byron or Scott but stumbles on a threadbare copy of an old book and, as she reads, it is “as if she had been wakened in the night by a strain of solemn music telling of beings whose souls had been astir while hers was in a stupor.” In stumbling on “The Imitation” Tulliver enters a period of intense spirituality and renounces the world.

During World War One the book was special, too, for Edith Cavell, a British nurse and devout Anglican, who helped 200 allied soldiers escape from German occupied Belgium. Cavell was captured, sentenced to death, and shot by firing squad. She was quoted as saying, “I can’t stop while there are lives to be saved”. On the day of her execution she inscribed a message to the man she loved in her copy of Thomas a Kempis’ classic.

Closer to our own times, in 1978, it was reported that “The Imitation” was the book which Pope John Paul I (Albino Luciani) had been reading in the Vatican at the time of his death; and it was the book which my friend James Mawdsley asked for when he was imprisoned for more than a year by the Burmese military junta.

James Mawdsley – who suffered imprisonment in Burma for demonstrating against military rule and for the rights of the ethnic minorities

“The Imitation” was also admired by St.Ignatius of Loyola, by St.Thomas More, and by the Trappist monk, Thomas Merton. The slave trader, John Newton, composer of Amazing Grace, and the great John Wesley both said that “The Imitation” had influenced their decision to become Christians.

monk, Thomas Merton. The slave trader, John Newton, composer of Amazing Grace, and the great John Wesley both said that “The Imitation” had influenced their decision to become Christians.

James Mawdsley – who suffered imprisonment in Burma for demonstrating against military rule and for the rights of the ethnic minorities